This article was originally published in OrionOnline.

Precarious dwellings in North Sulawasi, Indonesia.

Photos: iStockphoto.

A villa miseria outside Buenos Aires, Argentina, may have the worst feng shui in the world: it is built in a flood zone over a former lake, a toxic dump, and a cemetery. Then there’s the barrio perched precariously on stilts over the excrement-clogged Pasig River in Manila, Philippines, and the bustee in Vijayawada, India, that floods so regularly that residents have door numbers written on pieces of furniture. In slums the world over, squatters trade safety and health for a few square meters of land. They are pioneers of swamps, floodplains, volcano slopes, unstable hillsides, desert fringes, railroad sidings, rubbish mountains, and chemical dumps — unattractive and dangerous sites that have become poverty’s niche in the ecology of the city.

Cities have absorbed nearly two-thirds of the global population explosion since 1950, and are currently adding a million babies and migrants each week. Dhaka, Bangladesh; Lagos, Nigeria; and Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, today are each approximately 40 times larger than they were in 1950. According to the Financial Times, China in the 1980s alone added more city dwellers than did all of Europe (including Russia) during the entire 19th century.

In this process of rampant urbanization, the planet has become marked by the runaway growth of slums, characterized by overcrowding, poor or informal housing, inadequate access to safe water and sanitation, and insecurity of tenure. U.N. researchers estimate that there were at least 921 million slum dwellers in 2001 and more than 1 billion in 2005, with slum populations growing by a staggering 25 million per year.

Today, new arrivals to the urban margin confront a condition that can only be described as marginality within marginality, or, in the more piquant phrase of a desperate Baghdad slum dweller quoted by The New York Times, a “semi-death.” An International Labor Organization researcher has estimated that the formal housing markets in the Third World rarely supply more than 20 percent of new housing stock; out of necessity, people turn to self-built shanties, informal rentals, pirate subdivisions, or the sidewalks. These are moves of sheer survival. And because the geographic location of slums is becoming more and more marginal, the destructive power of natural elements leaves today’s slum residents in an ever more vulnerable state.

Tin shacks on the outskirts of Johannesburg.

Where There’s Folk, There’s Fire

Slums begin with bad geology. The shantytown periphery of Johannesburg, South Africa, for example, conforms unerringly to a belt of dangerous, unstable dolomitic soil contaminated by generations of mining. At least half of the region’s nonwhite population lives in informal settlements in areas of toxic waste and chronic ground collapse. Likewise, the highly weathered lateritic soils underlying hillside favelas in Belo Horizonte and other Brazilian cities are catastrophically prone to slope failure and landslides. Rio de Janeiro’s more famous favelas are built on equally unstable soils atop denuded granite domes and hillsides that frequently give way — with deadly results.

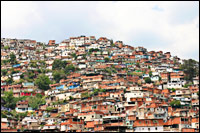

Caracas, Venezuela, however, with a population of 5.2 million in 2005, is the soil geologist’s “perfect storm”: slums housing almost two-thirds of the city’s population are built on unstable hillsides and in deep gorges surrounding the seismically active Caracas Valley. At one time vegetation held the friable schist in place, but brush clearing and cut-and-fill construction have destabilized the densely inhabited hills and precipitated a radical increase in major landslides and slope failures — from less than one per decade before 1950 to the current average of two or more per month.

In mid-December 1999, an extraordinary storm clobbered northern Venezuela. A year’s worth of rain fell in a few days upon already saturated soil; indeed, rainfall in some areas was reckoned to be a once-in-a-millennium event. The result was flash floods and debris flows in Caracas — and along the Caribbean coast on the other side of the Avila Mountains, where an onrush of 1.8 million tons of debris left the coastal resort of Caraballeda devastated. The storm killed an estimated 32,000 people and left 140,000 homeless and another 200,000 jobless.

What the Caracas region is to landslides, metropolitan Manila is to frequent flooding. In July 2000 a typhoon deluge caused the collapse of a notorious “garbage mountain” in Quezon City’s Payatas slum, burying 500 shacks and killing at least a thousand people.

Earthquakes make even more precise audits of the urban housing crisis; seismic hazard is the fine print in the devil’s bargain of “informal” housing marked by poor construction. Seismic destruction usually maps poor-quality brick, mud, or concrete residential housing with uncanny accuracy.

But the urban poor do not lose much sleep at night worrying about earthquakes or even floods. Their chief anxiety is a more frequent and omnipresent threat: fire. Slums, not Mediterranean brush or Australian eucalyptuses, are the world’s premier fire ecology. Their mixture of flammable dwellings, extraordinary density, and dependence upon open fires for heat and cooking is a superlative recipe for spontaneous combustion. A simple accident with cooking gas or kerosene can quickly become a megafire that destroys hundreds or even thousands of dwellings. Fire spreads through shanties at stunning velocity, and fire-fighting vehicles, if they respond at all, are often unable to negotiate narrow slum lanes.

To make matters worse, slum fires are often anything but accidents. Rather than bear the expense of court procedures or endure the wait for an official demolition order, landlords and developers frequently prefer the simplicity of arson. Manila has a particularly notorious reputation for suspicious slum fires, especially in areas targeted for industrial development. Urban sociologist Erhard Berner describes a favorite method of Filipino landlords: to chase a “kerosene-drenched burning live rat or cat — dogs die too fast — into an annoying settlement … The unlucky animal can set plenty of shanties aflame before it dies.”

World Bank on It

All the classical principles of urban planning, including the preservation of open space and the separation of noxious land uses from residences, are stood on their heads in poor cities. Almost every large Third World city with some industrial base has a Dantean district shrouded in pollution and located next to pipelines, chemical plants, and refineries: Mexico City’s Iztapalapa, São Paulo’s Cubatão, Rio’s Belford Roxo, Jakarta’s Cibubur, Tunis’s southern fringe, southwestern Alexandria, and so on. The world usually pays attention to such fatal admixtures of poverty and toxic industry only when they explode with mass casualties, as happened at Bhopal, India, in 1984, when an accident at a Union Carbide chemical plant killed 20,000 people.

Urban theorists have long recognized that the environmental efficiency and public affluence of cities require the preservation of ecosystems, open spaces, and natural services: cities need them to recycle urban waste products into usable inputs for farming, gardening, and energy production. And along with intact wetlands and agriculture, sustainable urbanism presupposes a basic level of safety — of meteorological, hydrological, and geological stability, and protection against disasters like floods or fire. None of those conditions can hold in most Third World cities. Suffering under a series of crushing pressures, most recently a quarter-century-old regime of Draconian international economic policies, cities are systematically polluting, urbanizing, and destroying their crucial environmental support systems.

Wealthy cities in vulnerable sites such as Los Angeles or Tokyo can reduce geological or meteorological risk through massive engineering projects. And national flood insurance programs, together with fire and earthquake insurance, can guarantee residential repair and rebuilding in the event of extensive damage. In the Third World, by contrast, slums that lack potable water and latrines are unlikely to be defended by expensive public works or covered by disaster insurance.

Researchers writing in the journal Cities point out that foreign debt makes such infrastructure investment ever more unlikely. “Structural adjustment” — the protocols by which indebted countries surrender their economic independence to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund — drives sinister trade-offs that favor export-oriented production, competition, and efficiency at the expense of disaster-vulnerable settlements.

Feeling the squeeze, in more ways than one.

The global forces pushing people from the countryside seem to sustain urbanization even when the pull of the city is drastically weakened by debt and economic depression. As Deborah Bryceson emphasizes in her summary of recent agrarian research, the IMF and World Bank policies of the 1980s and 1990s caused unprecedented upheaval in the global countryside. One by one, she writes, national governments gripped in debt lost access to agricultural subsidies and support for rural infrastructure. Latin American and African nations abandoned peasant “modernization” efforts and deregulated national markets, subjecting peasant farmers to the “sink-or-swim” economic strategy of international financial institutions. Pushed into global commodity markets, agricultural producers found it hard to compete.

These anti-peasant policies had the same results throughout much of the developing world. As local safety nets disappeared, poor farmers became increasingly vulnerable to any exogenous shock: drought, inflation, rising interest rates, or falling commodity prices. (Or illness: an estimated 60 percent of Cambodian peasants who sell their land and move to the city are forced to do so by medical debts.) Meanwhile, rapacious warlords and chronic civil wars, often spurred by the economic dislocations of debt-imposed structural adjustment or foreign economic predators (as in the Congo and Angola), were uprooting whole countrysides.

Cities — in spite of their stagnant or negative economic growth — have simply harvested this world agrarian crisis. Peasants had no choice but to become urban.

The Waste Land

The fallout has been predictable: hundreds of millions of new urbanites must further subdivide the peripheral economic niches of personal service, casual labor, street-vending, ragpicking, begging, and crime. With its high-tech border enforcement blocking large-scale migration to the rich countries, the new world order has dictated a formula for the mass production of slums, and for rising suffering from flood, slides, quakes, and fire.

But of all the dangerous ecological symptoms of runaway urban poverty, none poses a bigger threat than overflowing waste. The chronic shortfalls between the rates of trash generation and disposal in Third World cities are often staggering: the average collection rate in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, is barely 25 percent; in Karachi, Pakistan, 40 percent; and in Jakarta, Indonesia, 60 percent. The city planning director in Kabul, Afghanistan, complained to The Washington Post that his city is becoming “one big reservoir of solid waste … Every 24 hours, 2 million people produce 800 cubic meters of solid waste. If all 40 of our trucks make three trips a day, they can still transport only 200 to 300 cubic meters out of the city.”

Outside Hanoi, Vietnam, where farmers and fishers are constantly uprooted by urban development, urban and industrial effluents are now routinely employed as free substitutes for artificial fertilizers. When researchers writing for the journal Environment and Urbanization questioned this noxious practice, they discovered cynicism among vegetable and fish producers about the “rich people” in cities. “They don’t care about us and fool us with useless compensation [for farm land],” as one purveyor put it, “so why not take some form of revenge?”

The subject of human waste is, of course, indelicate; but it is a fundamental problem of city life from which there is surprisingly little escape. Lovly Josaphat, a resident of Cité Soleil, the largest slum in Haiti’s capital Port-au-Prince, told author Beverly Bell, “I’ve suffered a lot. When it rains, the part of the Cité I live in floods and the water comes in the house. There’s always water on the ground, green smelly water, and there are no paths. The mosquitoes bite us. My four-year-old has bronchitis, malaria, and even typhoid now … The doctor said to give him boiled water, not to give him food with grease, and not to let him walk in the water. But the water’s everywhere; he can’t set foot outside the house without walking in it. The doctor said that if I don’t take care of him, I’ll lose him.”

Green, smelly water everywhere. “Every day, around the world,” according to public-health expert Eileen Stillwaggon, “illnesses related to water supply, waste disposal, and garbage kill 30,000 people and constitute 75 percent of the illnesses that afflict humanity.” Indeed, digestive-tract diseases arising from poor sanitation and the pollution of drinking water are the leading cause of death in the world, affecting mainly infants and small children. Open sewers and contaminated water are likewise rife with intestinal parasites such as whipworm, roundworm, and hookworm that infect tens of millions of children in poor cities. Cholera, the scourge of the Victorian city, continues to thrive off the fecal contamination of urban water supplies, especially in African cities like Antananarivo, Madagascar; Maputo, Mozambique; and Lusaka, Zambia, where UNICEF estimates that up to 80 percent of deaths from preventable diseases (apart from HIV/AIDS) arise from poor sanitation.

“At any one time,” adds a 1996 report by the World Health Organization, “close to half of the South’s urban population is suffering from one or more of the main diseases associated with inadequate provision for water and sanitation.” Although clean water is the cheapest and single most important medicine in the world, public provision of water remains widely inadequate, and often competes with powerful private interests. In Dhaka, vendors mark up the cost of water — often from municipal sources — by 500 percent; in Faisalabad, Pakistan, 6,800 percent. Unable or unwilling to pay the extortionate price of water from vendors, some Nairobi, Kenya, residents resort to desperate expedients, including, two local researchers write, “the use of sewerage water, skipping bathing and washing, using borehole water and rainwater, and drawing water from broken pipes.”

And Adjustment for All

While the restructuring of Third World urban economies has contributed to dangerous health conditions, it has also gutted the response to those conditions. Since the late 1970s, international economic policy has devastated the public provision of health care, particularly for women and children. As the Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights points out, structural adjustment programs “usually require public spending, including health spending (but not military spending), to be cut.” In Latin America and the Caribbean, according to a World Bank researcher, the enforced austerity during the 1980s reduced public investment in sanitation and potable water, thus eliminating the infant survival advantage previously enjoyed by poor urban residents. In Mexico, following the adoption of a second adjustment program in 1986, the percentage of births attended by medical personnel fell from 94 percent in 1983 to 45 percent in 1988, while maternal mortality soared from 82 per 100,000 in 1980 to 150 in 1988.

In Ghana, “adjustment” not only led to an 80 percent decrease in spending on health and education between 1975 and 1983, it also caused the exodus of half of the nation’s doctors. Similarly, in the Philippines in the early 1980s, per-capita health expenditures fell by half. In oil-rich but thoroughly “adjusted” Nigeria, a fifth of the country’s children now die before age five. Economist Michel Chossudovsky blames the notorious outbreak of bubonic plague in Surat, India, in 1994 upon “a worsening urban sanitation and public-health infrastructure which accompanied the compression of national and municipal budgets under the 1991 IMF/World Bank-sponsored structural-adjustment program.”

The examples can easily be multiplied: everywhere, obedience to international creditors, whose policies helped create slums in the first place, has dictated cutbacks in medical care and precipitated the emigration of doctors and nurses, the end of food subsidies, and the switch of agricultural production from subsistence to export crops.

More recently the World Bank has relentlessly pressured aid recipients to open themselves to global competition from private First World health-care providers and pharmaceutical companies. The bank’s 1993 “Investing in Health” report outlined the new paradigm of market-based health care, as described by Fantu Cheru, a leading U.N. expert on debt: “limited public expenditure on a narrowly defined package of services; user fees for public services; and privatized health care and financing.” A sterling instance of the new approach was Zimbabwe, where the introduction of user fees in the early 1990s led to a doubling of infant mortality. As Cheru emphasizes, the coerced tribute that the Third World pays to the First World has meant the literal difference between life and death for millions of poor people.

But if ecological reality prevails, it won’t stop there. Today’s mega-slums are unprecedented incubators of new and re-emergent diseases that can travel across the world at the speed of a passenger jet. And, as the imminent peril of avian influenza indicates, economic globalization without concomitant investment in a global public-health infrastructure is a formula for catastrophe. It takes only a little imagination — the thought of a series of ill-fated airplane trips — to remind us that we’re all living on the same planet of slums, under the same economic regime.

The conditions creating the slums — greed, inequity, poor planning, and disrespect for human rights — are human forces, but they tend to intensify the earth’s natural forces. Those forces, ecological and biological, don’t always behave as predictably as we would like, or stay within their bounds.

To read an extended version of this article, request a free trial issue of Orion Magazine.