It looks like one of the main take-aways from the Congress for the New Urbanism 18 conference is something being labeled “agrarian urbanism.” Fast Company is calling it the “new new urbanism” and Treehugger has described the notion as the next phase in the evolution of this 30-year old movement. New Urbanism leader Andrés Duany, in particular, has been pushing pretty hard in this direction for the last couple of years.

Briefly, the idea is that walkable neighborhoods could be intentionally structured so that food production is integrated into the physical form and the lifestyle of the inhabitants. In other words, it’s a synthesis between urban and rural.

Instead of embedding hamlets within a rural landscape, the garden block embeds pockets of agriculture within the urban landscape. It is not a stand-alone community but just another gene sequence to be spliced into the DNA of existing inner suburbs and cities.

Of course, this new new urbanism is really no newer than the old new urbanism was (but that’s fine). One of the primary motivations behind Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow concept was to connect working-class households with a viable food supply to relieve some of their financial stress. He landed on the number of 12 dwelling units per acre (DUA) as the magic density for self-sufficiency with affordability, and he worked out a form of common land ownership to help it along. Urban planner Christopher Alexander thought that something more like a tenth of an acre was necessary to supply vegetables to a family of four. He had plenty of practical, timeless advice for arranging an urban living space accordingly. More recently, some architects have been using the word “rurbalization” to describe this sort of synthesis. Having recently passed through the grad-school circuit myself, I can attest to a strong interest in food systems among new graduates.

I think these are good trends. Local food systems should inform urban design and vice versa, but I’m not sure the new developments being modeled have been able to find this synthesis without swallowing one side with the other — specifically, subsuming the urbanism into the bucolic landscape. This seems to be the case with Southlands in British Columbia and Serenbe in the exurbs of Atlanta. Kaid Benfield has this to say about these “farming is the new golf” developments,

“In theory, these “new towns” are great — self-contained entities providing walkability, efficiency, and all the services of a community within the development. So, their proponents (nearly all of whom profit from them, one way or another) claim, it is a good thing to build them almost anywhere. In practice, though, the nearby once-remote locations soon become filled with sprawl, in no small part because of the initial development, and the theoretical self-contained transportation efficiency never comes. They become commuter suburbs, just with a more appealing internal design than that of their neighbors.”

So can this vision work? Or is building agrarian urbanism like serving a glass of hot cold water? I’d like to play with this a little and consider what it would look like if we followed Duany’s vision but flipped it on its head. Instead of embedding hamlets within a rural landscape, the garden block embeds pockets of agriculture within the urban landscape. It is not a stand-alone community but just another gene sequence to be spliced into the DNA of existing inner suburbs and cities.

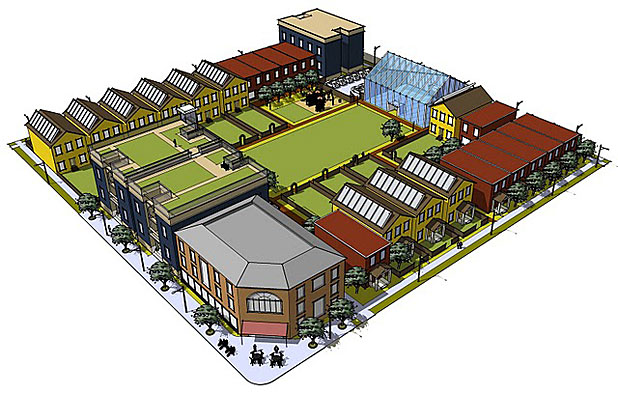

Start with the standard grid. It can be found all over North America, but the following sketch is based on the 340-by-340-foot block in the Fan neighborhood of Richmond. Cobble together property ownership for the whole block into something like a community land trust. Households would own their home individually but share ownership of the land with the other 38, in this case, units on the block. Certain commitments to planting and maintaining the garden, either personally or through payment, would be built into an HOA contract.

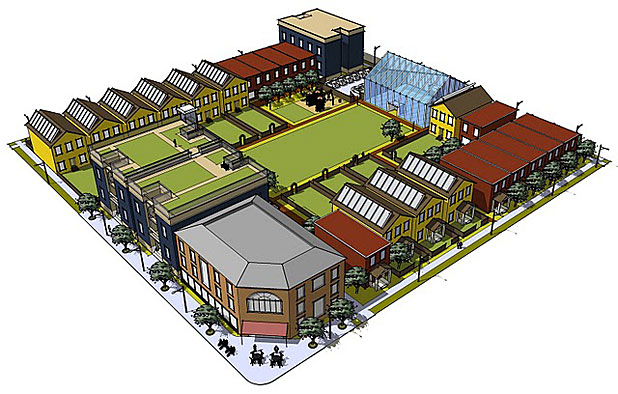

(Daniel Nairn renderings)

(Daniel Nairn renderings)

The exterior of the block functions as in any other urban area. The public streets are activated by the fronts of the buildings and streetscape features, and the full range of transportation access to the rest of the city is available. The interior, on the other hand, is devoted to the more constrained social scale of the block community, and the structures serve as a wall protecting this garden area. Enclosure is necessary to provide a degree of privacy, to protect produce from theft and vandalism, and to keep animals from wandering.

By the numbers, this block allows a density of 15 DUA while keeping 28 percent of all land for growing produce. This is not food self-sufficiency, but I’m personally not too worried about these kinds of absolutes.

Here are some of the pieces:

Mix of housing types: One might expect retirees and young families alike to be attracted to growing their own food, but there is a broad range in housing needs between these two groups. Allowing a range of housing types could facilitate lifecycle diversity, as well as allowing those from different income levels to share the same space. The larger homes include their own growing plot delineated by a short fence.

Shared resources: The shady northern side of the condo buildings is a place for the utilitarian functions. Gardening requires many resources that can be shared by the whole block. A tool shed is accessed from the side by the glass elevator. A water cistern collects and stores runoff from the buildings above. Chicken coops are lined up against the building. Although chickens need sunlight, some shade could benefit them as well. Maybe they could be on wheels. The composting bins are directly in front of the block’s dumpster, so households can deposit their organic waste while taking out the trash.

Childrens’ area: The playground and “kindergarten” is in full view of the whole grounds. Children have their own 24′ by 31′ plot to grow whatever they choose. A row of fruit trees creates a sound barrier for the adjacent rowhouses. Being within the enclosed communal area allows parents a certain assurance of safety.

Green roof: I know these things are expensive for now, but in this case it’s integral to the whole concept. Connected directly to the rest of the grounds by an outdoor elevator, it expands the growing area measurably. Less tangibly, the views to north into the block help create a sense of internal cohesion, and the southern views to the rest of the city a sense of external connection.

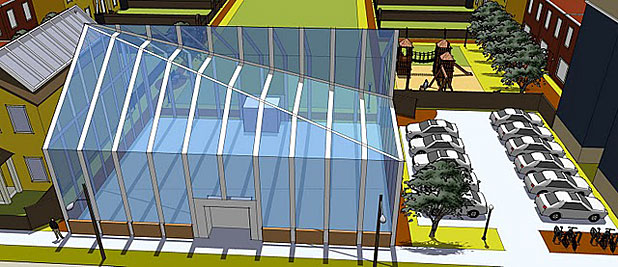

Greenhouse and car sharing: A greenhouse is one of the most efficient uses of solar energy, and it’s necessary in most climates for extending the growing season. A single 4100 sq. ft. greenhouse should be sufficient to meet the needs for the whole block. There is off-street parking available at a rate of roughly one space per three units. The relative paucity of spaces may be compensated for by car-sharing. For areas with greater transit accessibility, this lot could be substituted with two homes.

Corner store: The corner store is the public interface of the block and a neighborhood shopping hub. Possibly, excess produce and supplies from the garden could be sold here. The upper floors could be leased out to offices or any other reasonably compatible use.

So what do you think? Would you want to live in a block like this?

Republished with permission from Discovering Urbanism.