You probably would’ve never heard of the fuzzy little fruit known as the kiwi if it hadn’t had a Norma Jean Mortenson moment and changed its name from “Chinese gooseberry.” Same with avocado, which achieved superstardom after dropping the name “alligator pear.” Can you imagine millennials emptying their bank accounts to buy alligator-pear toast?

Marketing works. But you wouldn’t know it from the strategy employed by environmentalists trying to get people to eat less meat. That strategy: Spread the message that a lot more people could eat with a lot less land if we simply cut back our meat-eating habit. And if it doesn’t stick? Beat people repeatedly over the head with the same message.

It’s a failed effort by any measure. A measly 5 percent of Americans call themselves vegetarians, and more than 80 percent of vegetarians eventually return to the way of the flesh. Americans ate a record amount of meat last year — some 72 billion pounds (though on the bright side, we are shifting to less environmentally harmful meats).

Now, finally, people are considering new strategies. Daniel Vennard, who directs the World Resources Institute’s Better Buying Lab project, has been working with companies that feed a lot of people — like Google, Hilton, and Sodexo — to make non-meat choices more attractive by using behavioral economics and marketing. WRI has just published a summation of the findings from this work.

“We joke that this is just marketing 101 for plant-based foods,” said Daniel Vennard, who directs the project. “It’s really simple principles, like talking about what delights people.”

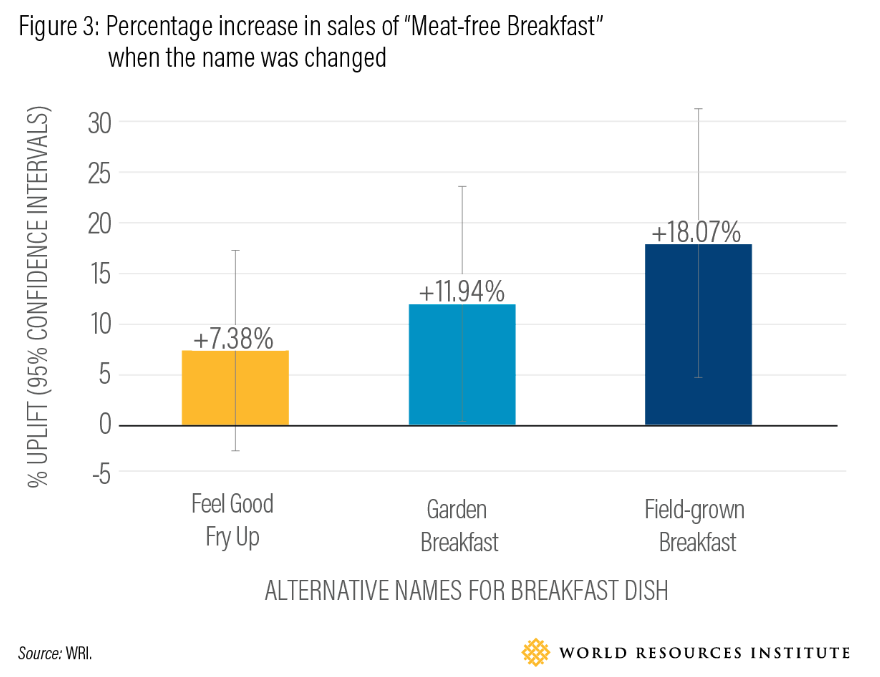

In other words, if you want to sell food, talk about what it tastes like and where it comes from, not what you avoid by eating it. For example, Vennard and collaborators convinced Sainsbury’s, the second largest supermarket chain in the United Kingdom to tweak the menu in their market cafe in the seaside town of Truro, England. It changed its “meat-free sausage and mash” to “Cumberland-spiced veggie sausage and mash” and saw sales soar 76 percent. When a Panera Bread store in Los Angeles renamed its “Low Fat Vegetarian Black Bean Soup” to “Cuban Black Bean Soup,” sales jumped 13 percent. Do you need to read this Stanford study to discover whether people were more enticed by the “zesty ginger-turmeric sweet potatoes” or the “cholesterol-free sweet potatoes”?

Language has a profound effect on the way we experience food, Vennard said. He cited a study where psychologists gave participants identical milkshakes, but labeled some “sensible” and others “indulgent.” Afterward, the people who had drunk the “sensible” shakes were hungry for more. They had three times the hunger-stoking hormone ghrelin in their systems as did the people who’d had the “indulgent” shake.

Vennard was a little surprised that veggie advocates weren’t already employing these branding ideas. The meat industry, however, clearly understands the power of marketing. For instance, there’s this piece of muscle from a beef-steer’s shoulder that butchers used to toss into the grinder along with all the other cheap scraps to make hamburger. After rebranding that muscle the “flat iron steak,” it became a sensation, with $70 million in sales in 2012.

In December, I wrote about another WRI report that looked at how the world could feed the 10 billion people expected to inhabit the planet in 2050. If we keep things as they are, getting all of them fed “would require putting an area twice the size of India under plow and pasture while emitting as much carbon as 13,000 coal plants running nonstop for a year.” Curbing our appetite for meat is a key part of preventing that catastrophe, but meat guys are beating the faux-leather pants off the veggie marketers. Vennard thinks that food companies will soon catch on. “When we started this two years ago there was practically nothing studying the marketing of plant-based food. It’s really a simple and cheap thing to change.”