Thinking outside the loft.

Catch the aboveground S train in Brooklyn and you’ll whiz through the neighborhood of Crown Heights, an industrial pocket of warehouses and factories that once stored and manufactured everything from artillery to pickle jars. These days, the buildings you pass appear to be abandoned relics in a bleak concrete landscape. But then, just as T.S. Eliot is coming to mind — “What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow / Out of this stony rubbish?” — you hurtle by a bright green oasis of richly vegetated roofs and a glossy black array of solar panels on a refurbished 1850s warehouse.

This anomalous building has just been renovated by Brooklyn sculptor Benton Brown, 31, and his wife, Susan Boyle, 30. Both novices in the fields of construction and engineering prior to this project, Brown and Boyle managed to achieve a mind-boggling feat of ingenuity and perseverance. Over two and a half years, they transformed a 14,000 square-foot derelict brewery and ice-storage house into an apartment building of such style, sustainability, and sophisticated engineering that it establishes the couple as pioneers among a new generation of green builders.

Susan Boyle and Benton

Brown.

Next month, Brown and Boyle will finally declare their project complete. The building houses six loft units complete with radiant heating, natural ventilation, Energy Star appliances, a rain-water collection system, a high-efficiency condensing boiler, and vast expanses of super-insulated, floor-to-ceiling glass windows. Solar energy provides nearly half of all the building’s electricity.

The project has been so successful that the couple won a $75,000 “Green Cinderella” grant from Keyspan Energy Company to cover one-third of the clean-technology costs, and are on track to get a silver rating from Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) — the gold standard in green building ratings. What’s more, they have a waiting list of potential tenants lined up to lease their units, and they expect to entirely recoup their sizable investment in this project within two decades.

Above all, having approached their project with a do-it-yourself, learn-as-you-go philosophy, the couple has proven that anyone can be a pioneer in sustainable building. Anyone, that is, with a basic knowledge of construction, a fearless relationship to blow torches, a penchant for grant writing, super-human patience with Building Department code and green-construction manuals — oh yes, and a network of private investors.

Taming the Salvage Beast

When Boyle and Brown first encountered the old factory, it had been inhabited for the past 20 years only by a healthy population of rats and pigeons. So there wasn’t too much competition when, in November 2001, they made an offer on the old industrial carcass — pests and all — for a sum they decline to name but say was dirt cheap by New York standards.

Bathroom outfitted with salvaged

wood and fixtures.

Two years and $1.1 million later (with funds coming largely from private investments by friends and family), they had trained a team of seven unskilled workers, taken torch guns to I-beams, changed the floor elevations, added mezzanines and cantilevered balconies, and installed vegetated roofs, reused fixtures, a seven-kilowatt system of solar panels, and a long list of energy-saving mechanisms.

“We definitely got a few Masters degrees and built our home at the same time,” said Susan Boyle, the namesake of “Big Sue LLC,” the development company she started with Brown. The real Susan — who, despite having had no previous construction experience, was the subcontractor on the project — is petite as could be, standing not much higher than five feet tall. But when you hear her bark orders at workers (she’s been known to grab people nearly twice her size by the collar to make a point clear), the derivation of the company’s name becomes abundantly clear.

Having worked for years at Transportation Alternatives lobbying for better urban infrastructure for cyclists, Boyle says she has always been interested in focusing her environmental energies in urban spaces. “New York City, to me, is the greenest city in the world,” she said, “for the energy efficiency of its compact living and ease of public transportation.”

Brown, on the other hand, started out with little interest in the environmental aspect of the project. “I’ve never been much of a political activist,” he said. “All I knew about green building was, you know, yurts [and] structures made of tires and straw bales and stuff. It’s not my thing.”

What Brown grew to appreciate was the economic and construction logic behind green building. “It was just amazing to find out how much better sustainable building functions than conventional building, how logical it is,” he said. “I think of it more as ‘high-performance’ than eco-friendly.”

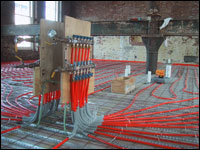

Installing the radiant heating system.

Brown admired, for instance, the logic behind radiant heating. Embedded in the concrete floors (made of 45 percent recycled fly ash, the waste material from burned coal), the heating system warms up the flooring. The concrete floors, in turn, emanate heat upward into the lower seven feet of the room — rather than the full 20-foot-high expanse of the lofty ceilings. And he appreciated the functionality of the green roof, which covers 2,400 square feet and is comprised of four inches of soil planted with low-maintenance groundcover plants. It’s comparable in cost to a regular roof and provides better insulation while also improving air quality and reducing runoff into city streets. (Water runoff in New York City overflows into the sewage system, thereby flushing sewage into the rivers surrounding Manhattan.)

Brown was also impressed by how easy it was to install the rooftop solar system by Unisolar. The system is comprised of adhesive-backed flexible solar panels that can be applied literally in hours to a standard pitched metal roof. “Peel-and-stick, pollution-free, electricity generated on site — not a bad concept,” said Brown.

As a sculptor, Brown also appreciated the aspects of sustainable building that go beyond technology and make use of reclaimed building material and found objects. Much of the construction material used in converting the warehouse, including the beams, bricks, doors, and window frames, were salvaged from the existing building. The kitchen cabinets are rehabbed lockers used by factory workers. All the tubs and pedestal sinks were purchased and delivered by a local scrap metal collector who roams the neighborhood in search of discarded fixtures. The couple’s commitment to reuse castaway items cut down significantly on cost. The only new fixtures in the rental units are the energy-efficient appliances.

Brown is no longer concerned that the project cramps his style. “You wouldn’t look at this [building] and go, ‘what an Earth-ship thing to do.'”

Crown Heights crowning glory.

LEED-ing the Way

Boyle, on the other hand, isn’t shy about her hopes that this project will be recognized for its planet-positive ingenuity and help mobilize a larger movement. “We want people to see, intuit, and understand the difference of a building like this,” she said. “The higher goal here is simply to motivate more people to want to live in this kind of environment and take on similar steps or projects,” she said. “We’re basically in the middle of an industrial sector. There’s not a whole lot in the way of parks or trees. So when people ride by on the elevated train and see one rooftop covered with vegetation and another covered with solar, it creates questions in their minds.”

Applying for the silver LEED certification is part of the couple’s commitment to promoting sustainable design. That designation would put their apartment complex on the map as the first certified residential green building in Brooklyn and contribute to its educational potential. “The LEED program is only about a decade old, and has a bad rap for being several steps away from user-friendly. Its guidelines are complex, but not complex enough that you can’t slog through the manual and figure it out,” said Boyle.

The payoff of LEED, she adds, is that you can quantify the benefits of building sustainably and share information with others embarking on similar projects. To this end, Boyle has gone out of her way to accommodate requests for student tours from professors at colleges and art schools in the city, including Columbia University and Parsons School of Design. She and Brown have also hosted tours of the building for dozens of city officials, developers, and energy-industry representatives.

“It’s been incredibly satisfying to get students and architects and city officials circulating throughout the building and watch them get a sense of what sustainability means, why it works, what it feels like,” said Boyle. “The hope is that they begin to see how it relates to their own lives.”

Interior motives.

But perhaps more gratifying than anything else for Boyle and Brown is the lesson they learned in perseverance. Brown says both he and his wife experienced “extremely high levels of stress for both of us throughout this whole project. Most of the time it has been a mad, jumping-around freak show.”

Take, for instance, the time one of their workers was wearing flip-flops while installing windows at 30-foot heights. Or the time a window installation failed during a snow storm, leaving them to work for days with the snow blowing in. Or the time an electrician drilled a hole in the radiant heating tubes, so they had to tear out the concrete floor and start over.

“I don’t know how we’ve made it, because working together and living together and loving each other is a hard combination,” said Brown. “We fought a lot, but I guess we’ve learned getting through this that our marriage is pretty durable.” Durable enough, in fact, to help establish sustainable design as a durable phenomenon as well — and to incite interest in it among a new generation of green builders.

Sustainable building was always hip among hippies. Then it started to spring up in gated movie-star compounds, yuppie ski towns, and lefty do-gooder cities. Recently, even corporate headquarters, suburban planned communities, low-income housing developments, and city government buildings have begun to make the solar switch. But for the most part, younger, urban crowds have yet to catch on. What Boyle and Brown have shown is that a hipster green-building subculture is viable for the rest of their generation.