This story was originally published by HuffPost and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

“Christmas,” Mariner Ostolaza said mournfully, like it’s the name of a loved one who died too young. “Do you know what a Christmas is in Puerto Rico?”

She sets her coffee down, freeing her hands to gesticulate pizzazz, and answers her own question. It starts on Thanksgiving and it ends in mid-January with Fiestas de la Calle de San Sebastián, a street festival.

“It’s three months of partying, drinking, and freaking good-ass music,” she said, sighing. “Being here, it was sad. My family over here is already Americanized, so they don’t do the same parties or the same traditions we have over there.”

The 28-year-old fled to Florida’s largest city in October after Hurricane Maria inundated Levittown, the middle-class San Juan suburb where she lived in a one-story home with her grandmother and great-grandmother. She agonized over the decision to leave.

The night the floodwaters came, just hours after the winds and rain subsided, she watched swarms of cockroaches and rats engulf entire lampposts as they scurried to drier heights — a nightmarish, almost Biblical omen. She had believed she might die as she navigated her packed 2005 Toyota Corolla through streets that had become fecal rivers.

She spent the next week wading through sewage, air-drying clothes and old love letters, and chasing evasive bouts of sleep in the sticky nights without air conditioning. Then, one morning while she waited in line for gasoline at 4 a.m., service blinked onto her phone for a moment, and she got a text from her aunt in Miami. A family friend working at Royal Caribbean secured spots for Ostolaza and her grandmothers on a cruise ship leaving San Juan the next morning.

“I didn’t want to come,” she said. But her job was less secure than it once was, since the hotel where she worked didn’t know when it would welcome tourists again. And her uncle, and — once she finished weeping — her mother, convinced Ostolaza leaving was the only choice. The next day, she joined her grandmothers, who were depending on her to be their English translator, and boarded the ship. She arrived in Miami on Oct. 3, her dad’s birthday, the first one she’d ever missed.

Nearly nine months later, Ostolaza feels stuck in a city with expensive housing, limited jobs and — the weather and plentitude of Spanish speakers aside — few resemblances to her island. Puerto Rico remains in shambles and without reliable electricity. Federal authorities have yet to even determine the final death toll from the storm, though Harvard University researchers this week pegged the number at 4,645 — 70 times the official tally and nearly three times higher than Hurricane Katrina in 2005. On Friday, a new hurricane season begins.

Roughly 136,000 Puerto Ricans fled to the mainland United States in the months after the storm. That figure, based on school enrollments as of last February, is expected to surge well above 200,000 when states release new data in September. Almost half of them stayed in Florida.

But few are settled. Ostolaza got a job waiting tables at a Puerto Rican restaurant in Kendall, south of Miami, but she still lives rent-free with her aunt and uncle. She is debating when, or whether, to go back, wondering if remaining in Miami, with its increasingly flood-prone streets and heedless waterfront construction, is any less delusional than returning to Puerto Rico in an era of rising seas and warming temperatures.

‘Miami can barely handle the people who live there now’

Ostolaza’s predicament demonstrates policymakers’ failure to prepare for sudden influxes of migrants fleeing the kind of extreme weather that is becoming more frequent as climate change worsens, scientists say. Her reality also highlights a more subtle effect of displacement, a quiet epidemic of homesickness and depression, particularly among Americans with as unique a culture as Puerto Ricans.

The problem threatens to become much worse in South Florida. Caribbean nations that neighbor Puerto Rico are particularly at risk, and not just from sea-level rise. Since the early 1980s, countries like Jamaica, Haiti, and St. Lucia began adopting neoliberal economic reforms pushed by the U.S. and the International Monetary Fund. These policies devastated agriculture on the islands, as study after study shows, forcing them to rely on imported food and bottled water, and revolve their entire economies around tourism.

“The only thing that keeps the entire Caribbean economy from completely collapsing is tourism,” said Jesse Michael Keenan, an expert in climate migration at Harvard University.

Like in Puerto Rico, where the island’s $70 billion public debt has strangled the local economy, financial hardship already makes many in the Caribbean eager to leave. When extreme weather ravages infrastructure and makes it difficult to import and distribute products, countries are thrown into chaos, and South Florida is the closest entry point to safety in the U.S.

Puerto Ricans heading to Orlando after Hurricane Maria. Pedro Portal / Miami Herald / TNS via Getty Images

“Miami can barely handle the people who live there now,” Keenan said. “It’s hard to imagine a future where they could handle much more influx from the Caribbean.”

Hurricane Maria became the deadliest disaster in modern U.S. history, not because it was a Category 5 storm, but due to the failure to provide emergency relief quickly enough, if at all. The Harvard survey found that the number of deaths soared in the months after the storm as a result of the interruption of medical care. About 14.4 percent of households reported losing access to medications, 9.5 percent said the widespread blackouts left respiratory equipment useless, 8.1 percent said nearby medical facilities remained closed, and 6.1 percent said there were no doctors at those clinics. Nearly 9 percent of households in remote, mountainous areas could not reach emergency services by phone.

In the weeks after the hurricane made landfall, food and medicine stayed packed in shipping containers as the Federal Emergency Management Agency struggled to find ways to distribute the much-needed goods around the storm-ravaged island. (The agency insisted they were retail goods, not aid.) Companies contracted by the agency failed to deliver millions of meals to hungry Puerto Ricans. Federal contractors hired to rebuild the island’s crippled electricity grid became the subject of corruption allegations. At one point, the company Whitefish Energy Holdings suspended work on power lines until Puerto Rico’s bankrupt electric utility paid up. Last month, Puerto Rico plunged into darkness yet again after an excavator working too close to a fallen transmission tower got too close to a high-voltage line.

The Trump administration, after some debate, tweaked welfare rules to allow Puerto Ricans to buy prepared meals with food stamps. But the White House refused to offer aid money to Puerto Rico in January, insisting the island undergo means testing that determined it was too rich to qualify for the funding, despite the poverty rate surging from 44.3 percent to 52.3 percent after the storm.

As the administration continues to ignore and marginalize scientists whose research warns that climate change is making the frequency, strength, and speed of hurricanes more cataclysmic, mismanaged relief efforts could well become a permanent fixture.

The federal government’s bungled response to the storm extended to the states that took in displaced Puerto Ricans. It took FEMA more than a month to activate a transitional housing program for displaced survivors. The agency planned to discontinue paying for Puerto Ricans to live in hotels in April. But after state and local officials scrambled to shore up funding to keep the Puerto Ricans housed, FEMA reversed its decision and approved a request to extend a transitional housing program to 1,700 Maria survivors. But that program expires on June 30 and FEMA has no plans to extend it again.

FEMA spokesperson Lenisha Smith said the agency was working “closely with survivors of Hurricane Maria from Puerto Rico, including those in Florida, on finding more permeant housing solutions.”

Finding permanent housing has been a struggle, particularly in Florida.

“They don’t have the money for renting any house that they can afford in Florida,” said Angel Marcial, a bishop with churches in Orlando, the top destination for Puerto Ricans in Florida. “Many of them don’t have enough money for the down payments or the deposit, even what they receive monthly is not enough for a monthly rent.”

But in Orlando, at least, the Puerto Rican community is filled with more recent arrivals and is close-knit, making it easier to access community services.

Miami, the second-strongest magnet for Puerto Ricans and almost twice Orlando’s size, is a bit tougher. The cost of living there is 10 percent higher, according to Expatistan, a site that compares living expenses between cities.

Puerto Ricans also don’t have central hubs in the city, like the Cuban and Haitian communities do. They’ve instead dispersed as the neighborhood once known as Little San Juan undergoes rapid gentrification. Land prices in Wynwood, a neighborhood just north of downtown, quintupled between 2012 and 2016, according to real estate data cited by The Real Deal. Lease rates more than doubled. For many, the neighborhood has become too expensive for natives, let alone newcomers.

Andrea Ruiz-Sorrentini, a University of Miami researcher studying how Puerto Ricans displaced by Hurricane Maria are adapting to Miami, said evacuees despaired over the dearth of go-to cultural locations in the city.

“There is not a renowned hub in Miami to go and experience what it is to be Puerto Rican,” she said, sitting in a rec room of a Puerto Rican cultural center in the Roberto Clemente Park, one of the last prominent emblems of Wynwood’s Puerto Rican heritage. “Yes, Wynwood exists, but in recent years it hasn’t been the same.”

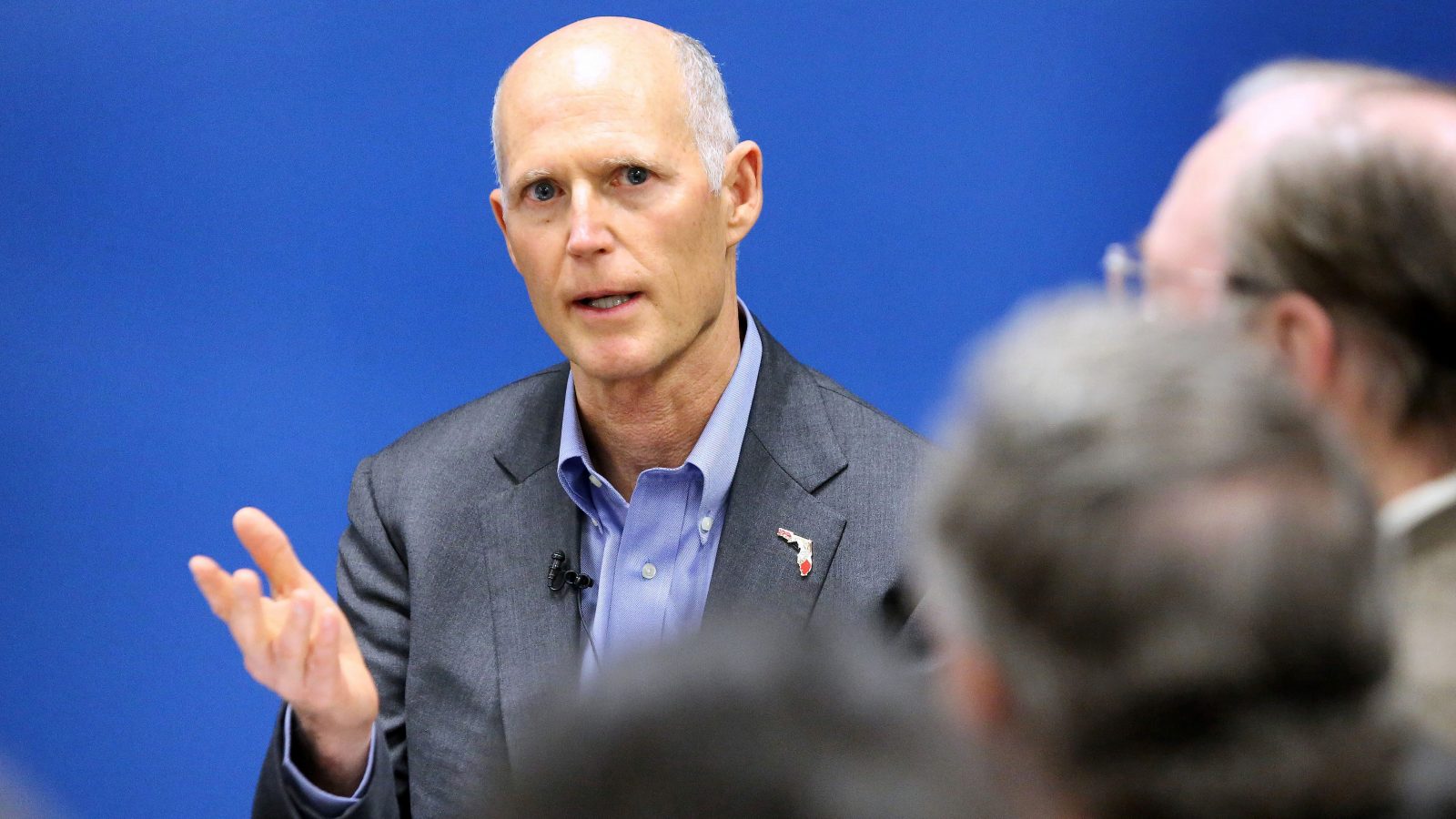

In October, Florida became the only state to enter into a host-state agreement with FEMA, and Republican Governor Rick Scott began urging federal officials to fund relief efforts. In January, nearly four months after the hurricane, the federal government granted Florida $13 million to help displaced Puerto Ricans find jobs. In response, Scott unveiled a new $1 million employment effort with the Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce and Ana G. Mendez University the next month.

Rick Scott speaks about the influx of Puerto Rico residents. Joe Burbank / Orlando Sentinel / TNS via Getty Images

Fewer than a quarter of the 20 actions a Scott spokesperson listed the administration as taking in response to Hurricane Maria dealt directly with displaced evacuees.

Florida’s stringent rules for accessing public services make the situation for poor displaced Puerto Ricans even more dire. Scott worked closely with the Trump administration to roll back rules that expanded Medicaid protections.

“That’s emblematic of Florida’s conservative approach to social services in general,” said Edwin Meléndez, an economist and the director of Hunter College’s Center for Puerto Rican Studies. “That means the community infrastructure, the nonprofits that provide services and the privatization of government leaves services not even comparable to those in the Northeast, where other Puerto Rican communities exist.”

‘These displaced Puerto Ricans will be climate voters’

The state’s cutbacks in welfare spending mirror its reluctance to spend money to prepare for climate change, despite facing some of the greatest risks from rising seas and extreme weather. Scott, who has long denied the science behind climate change, insisted during his reelection campaign in 2014 that his administration spent $350 million on sea-level-rise mitigation efforts. PolitiFact, the Florida-based fact-checking service, declared the claim “mostly false,” noting that the governor’s office included in that figure $100 million in sewer infrastructure that had nothing to do with sea-level rise. As recently as last year, conservationists accused Scott of ignoring global warming and pushing an Orwellian erasure of the words “climate change” from public documents.

The influx of new voters from Puerto Rico could tilt the Florida electorate against representatives who deny climate change.

Eight in 10 Latinos think global warming is happening, including nearly nine in 10 Spanish-speaking Latinos, according to 2017 survey data from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Sixty percent said they would vote for a candidate for public office because of their position on climate change, and 51 percent said they would join a campaign to convince elected officials to act on global warming. That number jumps to 61 percent among Spanish-speaking Latinos.

In Florida, where Latinos make up 16.4 percent of registered voters, polling by the Environmental Voter Project found the average Latino voter to be almost 10 percent more likely to care about climate change than the average non-Hispanic white voter. The group identified 514,691 Latinos who are already registered to vote and would be highly like to list “climate change or other environmental issues” as one of their top political priorities, and that doesn’t even count newly arrived Puerto Ricans with firsthand experience of the kind of storm scientists forecast to become more common as the planet warms.

The Harvard study found that the median age of Puerto Ricans who left after Hurricane Maria was 25, placing them in the millennial age group that tends to favor policy solutions to climate change.

“In short, every bit of data tells us that these displaced Puerto Ricans will be climate voters, and any candidate who ignores them (and their priorities) could easily lose the election because of it,” Nathaniel Stinnett, executive director of the Environmental Voter Project, said in an email.

That may be fueling some Florida Republicans’ concerns about newly registered Puerto Rican voters. John Ward, a candidate in the GOP primary for Florida’s 6th Congressional District, drew criticism last week for saying displaced Puerto Ricans should not be allowed to register to vote in Florida.

“I don’t think they should be allowed to register to vote,” he said in a video uploaded to YouTube by a Republican rival. “It’s not lost on me that, I think, the Democrat Party’s really hoping that they can change the voting registers in a lot of counties and districts, and I don’t think they should be allowed to do that.”

That hasn’t stopped people like Ostolaza. She registered to vote in Miami almost immediately after arriving in the city. She doesn’t know whom she plans to vote for in Florida’s Senate election this year, in which Scott is the Republican frontrunner to challenge Democratic incumbent Bill Nelson.

But she said she couldn’t vote for someone who rejects scientists’ warnings about climate change.

“Not after living through what I did, and seeing everything,” she said. “We’re the ones who suffer more.”

The next day, at Isla Del Encanto, the restaurant where she works, Ostolaza took an order for alcapurrias. On her way to the kitchen, she wisped by a large blue and white sign that read: Boricua Vota.