In a remote stretch of Costa Rica, where towering trees give way to spindly mangroves, mornings start with a roar. Monkeys high in the canopy howl to greet the sunrise. Hammers bang and tools scrape as workers hustle to beat the heat. Sawmills shriek from a grassy clearing, slicing enormous logs into smooth, broad planks.

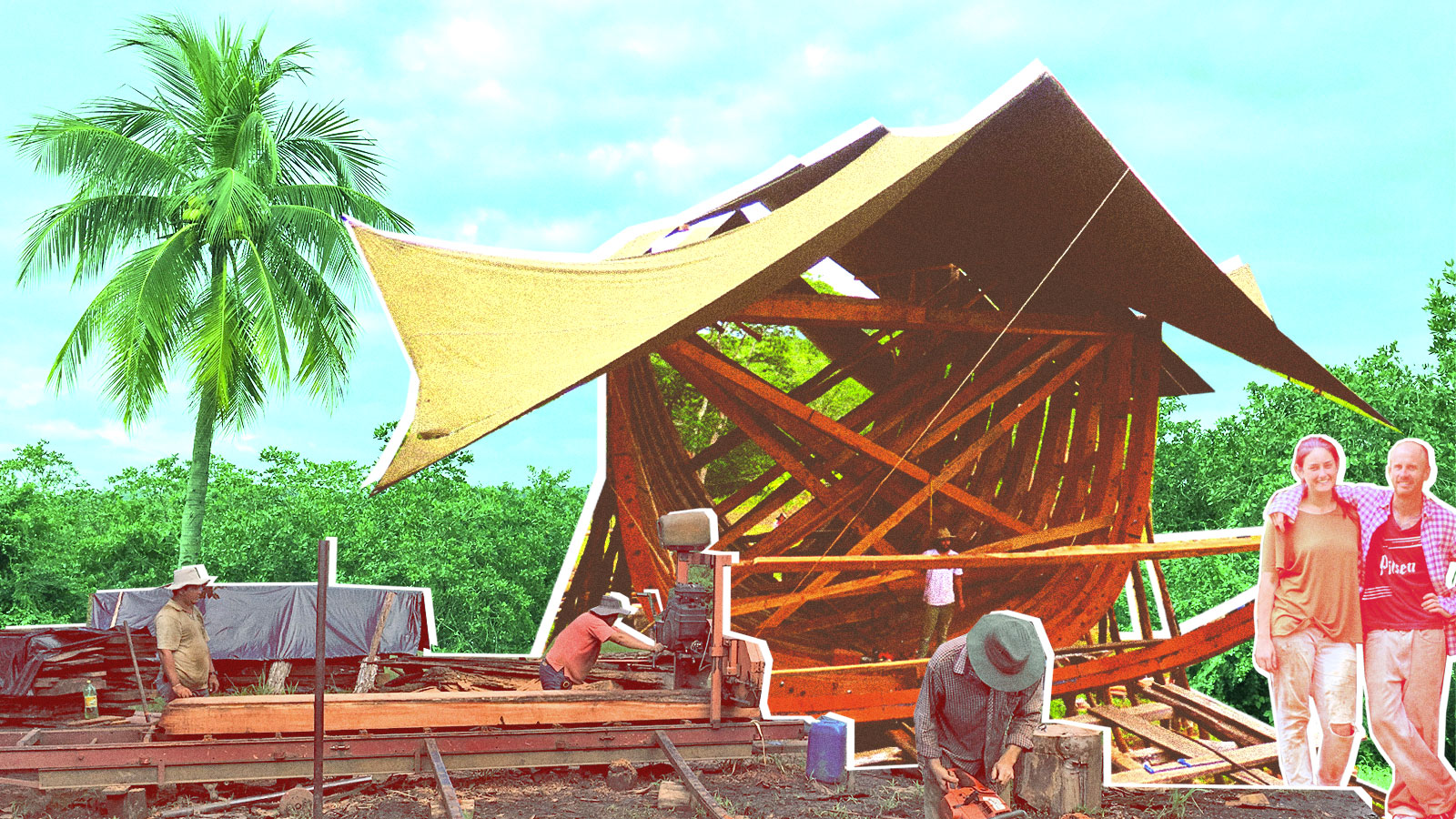

A makeshift shipyard is emerging here in Punta Morales, a tiny fishing town on the Pacific coast. The skeleton of a sailing ship has taken shape, with tall wood frames rising from a 106-foot-long spine like a rib cage. Once completed in late 2021, the Ceiba — named for the tropical tree — is expected to carry cargo throughout the Americas. The schooner will use canvas sails and an electric engine instead of burning bunker fuel, the dirty staple of the modern shipping industry.

SailCargo, a small Costa Rican startup, is building the vessel with dozens of local workers, visiting volunteers, and international investors. Their lumber comes from sustainably harvested and naturally fallen tamarind and other hardwoods. The team is planting thousands more trees to rebuild forests, produce future ship supplies, and offset emissions from the project. The startup also hopes to grow a profit someday by hauling spices, cotton, cacao, and other cargo on a fleet of wooden ships.

“We want to show that, from its inception, something can be completely regenerative and carbon neutral,” said Danielle Doggett, SailCargo’s co-founder and executive director.

The project is one part of a sweeping effort underway in Costa Rica to shun fossil fuels and embrace clean energy. Many see the tiny country as a model, a place where bold ideas can take hold and spread to the outside world.

Much of the push comes from the top. Earlier this year, President Carlos Alvarado adopted a plan to decarbonize the economy by 2050, vowing to make Costa Rica one of the first countries to achieve net zero emissions. Claudia Dobles, the first lady, is spearheading efforts to green the transportation sector by adding electric freight trains and battery-powered buses and taxis. In this country of 5 million people — where nearly all electricity originates from hydropower and renewable sources — vehicles are the single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions.

Grassroots efforts and private ventures like SailCargo play roles, too. In nearby Monteverde, a small town in the western cloud forest region, a local public-private council is installing electric car charging stations along popular ecotourism routes to reduce the use of gas-guzzling cars. Electric vehicle enthusiasts in various cities host free festivals and car shows to educate the public on petroleum-free transportation.

“Costa Rica doesn’t have to be seen only as a governmental story” on climate action, said Monica Araya, founding director of the nonprofit Costa Rica Limpia (“clean” in Spanish). “The energy that you see in the streets is actually from the citizens.”

Araya, who previously represented Costa Rica’s government in international climate talks, said it’s easy to dismiss her country’s initiatives as “cute” but ultimately futile. After all, much larger economies like the United States and China continue burning and producing fossil fuels with abandon, more than eclipsing any emissions cuts from Costa Rica. The country contributes roughly 0.2 percent of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions.

Still, Araya thinks these small-scale efforts offer instructive examples of how to rally people and inspire action in a world that often seems paralyzed by indifference or fear around climate change. “If you have a cause, and you have an ability to create a community, I think that is essential right now,” she said.

Costa Rica’s flagship

When I arrived in Punta Morales, in October 2017, Doggett picked me up on her motorbike and drove down bumpy roads to the coastal shipyard. The property juts into a saltwater bay in northwestern Costa Rica, with the Monteverde cloud forest to the north and the capital San José a few hours’ drive east. During my stay, Tropical Storm Nate devastated towns around us, choking roads with mudslides and washing away homes.

The shipyard held only a sagging one-room house and scattered tamarind planks. SailCargo had just started moving to the waterfront after months of fundraising, securing leases, and setting up the business in Monteverde. Lynx Guimond, Doggett’s co-founder, put down his chainsaw to greet me. He was building an office space: a treehouse made from fallen limbs and wood offcuts. I slept up there the first night, in a tent atop a suspended trampoline. Fireflies illuminated the pitch-black sky with flashes of green and yellow.

Doggett and Guimond, both from Canada, said a big reason they’re building the Ceiba in Costa Rica is because of the country’s strong environmental policies. About one-fourth of the country’s land falls within a national park, reserve, or wildlife refuge (at 19,700 square miles, Costa Rica is smaller than West Virginia). For each tree they buy or move, SailCargo must obtain a permit from the government, a cumbersome process which aims to ensure projects don’t contribute to deforestation.

But it doesn’t exactly hurt that Costa Rica is a lush, emerald gem of a place nestled between two oceans.

Woodworkers at SailCargo’s shipyard brace the Ceiba’s 2-ton stem. Danielle Doggett

Sitting at a cable-spool table, mosquitoes nipping our ankles, Doggett showed me a blueprint of the three-masted schooner that will soon fill this space. The Ceiba’s design was inspired by the 1907 ship Ingrid, which sailed cargo in Scandinavia long after sooty steamships and diesel engines came to dominate the seas.

Today, cargo ships haul roughly 90 percent of global trade — and all but a sliver run on fossil fuels. The shipping industry accounts for roughly 3 percent of the world’s total annual greenhouse gas emissions, though that share is projected to soar in coming decades if ships stick with fossil fuels. Cargo ships are also among the world’s largest emitters of sulfur oxides, which threaten human health, particularly in communities near busy ports and shipping routes.

As a result, shipping companies face mounting pressure from international regulators, public health officials, and others to adopt cleaner technologies and reduce pollution. SailCargo belongs to a growing contingent that’s looking to the past for solutions. In the Americas, Europe, and Pacific Island nations, sailors and deep-pocketed environmentalists are renovating old ships and building masted canoes to ferry people and cargo using wind power.

Doggett, a professional sailor, and Guimond, a skilled woodworker, met a decade ago on a sailing ship carrying rum from the Dominican Republic to France. They’ve since worked on other vessels, including the Dutch brigantine Tres Hombres and the German schooner Avontuur, cargo ships which ply the Atlantic Ocean and waters in northern Europe, carrying cardamom, organic coffee, and other foods to carbon-conscious consumers. Although some projects have carved out niche markets like these, many face financial struggles, in part because it can cost more to operate the ships — paying crew, port fees, and taxes — than they earn delivering small batches of cargo.

SailCargo is in talks with producers in Costa Rica and North America to establish regular trade connections between Pacific ports, which the company hopes will reduce expenses and provide stable returns. Craft breweries in Costa Rica, for instance, have expressed interest in importing U.S. barley. An organic avocado grower in Mexico is considering shipping products to Western Canada.

The ultimate goal, Doggett said, is to show that “a company can still turn a profit and not forget about the social and environmental aspects.”

Yet even if SailCargo and its companions can stay afloat financially, the amount of carbon emissions they can reduce or avoid will be largely symbolic given the scale of the global shipping industry. When finished, the Ceiba will hold up to 55,000 pounds of cargo, equal to about nine standard shipping containers. A new “mega” ship, by contrast, can carry over 20,000 containers. Worldwide, cargo ships moved 10.7 billion metric tons of goods in 2017, a scale made possible by power-plant-sized diesel engines and dirt-cheap bunker fuel.

“Sailing ships cannot address the volume of cargo we move today,” said Martin Stopford, a maritime economist based in England.

To curb emissions, mainstream shipping companies are retooling their massive metal freighters and tankers with energy-efficiency measures, fuel-saving software, hydrogen fuel cells, and biofuels. A handful of projects incorporate wind energy, but in the form of automated sails or spinning metal cylinders atop more conventional ships.

Still, Stopford thinks vessels like the Ceiba “have a part to play” in shipping’s transformation, particularly if sailing ships can harness trade winds to move swiftly and reliably, or if companies can establish solid markets for their premium products.

“I think of it as a niche player in the greater spectrum of green shipping,” Stopford said.

Multiplier effect

Over the last two years, SailCargo’s shipyard has transformed from piles of planks and a trampoline treehouse into a bustling construction zone. Beneath an enormous tarp, workers tug thick ropes to hoist the Ceiba’s curved frames into their upright position. In the outdoor kitchen, cooks boil plantains and stir big pots of rice and beans over the wood-burning stove.

“It’s beautiful, not just the ship itself but the whole community around it,” Marisol Vega Corrales told me recently by phone. Vega Corrales, who is from Punta Morales, works as SailCargo’s head chef. She also leads an association of women entrepreneurs who help prepare meals and sew canvas tarps. The shipyard is one of the only places to work in the area, she said.

SailCargo has so far raised more than $800,000 in private investments and in-kind donations, including machinery and lumber. To finish construction and meet its launch goal of late 2021, the company estimates it needs to raise at least $3 million more. Although SailCargo hasn’t received direct funding from the Costa Rican government, the team says it receives strategic advice and publicity from the country’s environmental and business development offices.

“We have resonated more with them, because we are a green project, rather than with traditional trading facilities like ports,” said Luis Pérez, the marketing and sales manager for SailCargo. “Our strongest message has been decarbonization.”

Last year, SailCargo won a small prize in a startup competition run by Costa Rica’s export promotion agency, PROCOMER. The team also landed a spot in a business incubation program run by the German development agency, GIZ, in San José. In September, Doggett will be a keynote speaker at Costa Rica’s top sustainable tourism conference. And she recently spoke at a green shipping forum in Panama, Costa Rica’s neighbor and one of the world’s most important maritime countries thanks to the Panama Canal.

On its own, a single wooden ship like the Ceiba will do little to transform the multi-trillion-dollar shipping industry. Much as Costa Rica itself, with its national decarbonization plan and grassroots support, won’t put much of a dent in global carbon emissions on its own. But that’s not the sole purpose of such initiatives, said Amanda Maxwell, who directs the Latin America Project at the Natural Resources Defense Council in Washington, D.C.

First steps make a difference, no matter who takes them. Small countries and tiny companies can develop programs that then gain a critical mass. In Latin America, for instance, cities like San José, Mexico City, and Medellín, Colombia have become hubs for clean transportation projects that spread across the region and around the world.

“This is where climate solutions are born that can be replicated in other countries with (a larger share) of global climate emissions,” Maxwell said.