In April, Senator Elizabeth Warren was the first 2020 presidential candidate to propose banning oil and gas leases on public lands, but she wasn’t the last. Now, a total of 18 Democratic candidates have signed onto the idea; some of them have vowed to do it on their very first day in office. The idea has picked up steam from the last presidential election cycle, when Hillary Clinton merely wanted to “phase out” the practice.

To Americans concerned about impending climate-pocalypse, that’s a major sign of progress. To the fossil fuel industry and many Republican members of Congress, it’s a sign of the End Times.

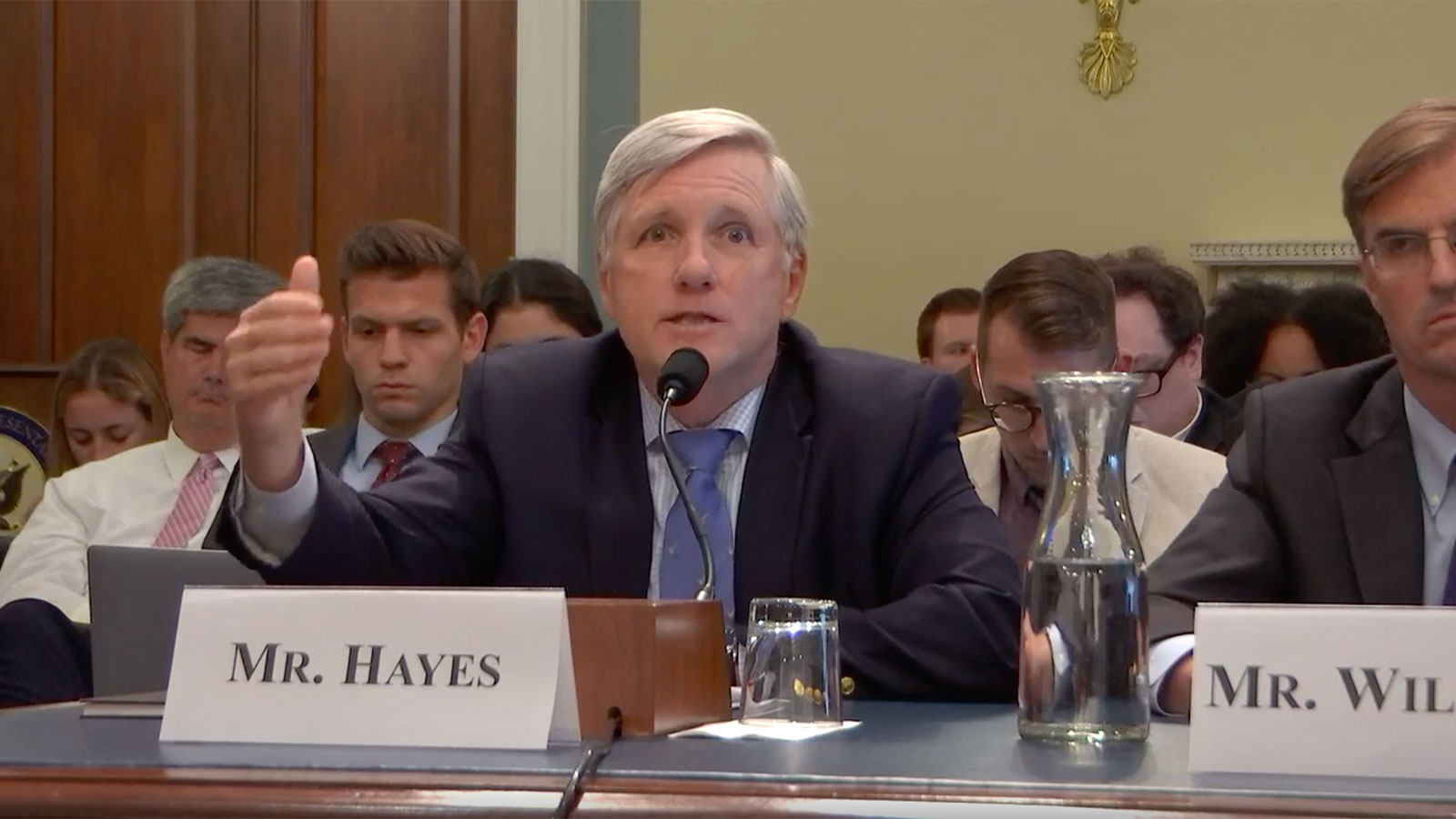

This tension was on full display at the House Natural Resources Committee hearing on Energy and Natural Resources on Tuesday — the committee’s first hearing in the 116th Congress on the environmental impact of fossil fuel production on public lands.

Democrats asked a panel of three environmental experts (and one spokesperson for the right-wing think tank the Heritage Foundation) a series of productive questions about how to reduce emissions from public lands. Republicans wanted to know why it was so cold in Arizona this May, if wildfire mitigation could perhaps help with the emissions coming from oil and gas development on public lands, and — most importantly — whether one of the witnesses, the head of an energy and science policy institute and holder of a Ph.D. in environmental management, “was familiar with statistics.”

The queries from the right side of the aisle might seem bizarre, but they’re par for the course when it comes to these climate-themed House Natural Resources Committee hearings (in an April hearing, Kentucky Republican Thomas Massie asked: “Did geology stop when we got on the planet?”). What was noteworthy about this hearing was the testimony from Nicolas Loris, the senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation. Instead of questioning humanity’s contribution to rising temperatures as he has done in the past, Loris tried a two-pronged approach.

First, he argued that eliminating emissions from fossil fuels on public lands “would not make any meaningful impact on climate change.” That doesn’t jibe with a new report from the Wilderness Society, which says that the projected emissions from oil and gas leases sold by the Trump administration surpass the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced by all 28 member countries of the European Union in a year. The study suggested that if the U.S. keeps selling public land leases to fossil fuel companies, the country won’t be able to uphold its part of the bargain to limit emissions to 1.5 degrees C — the threshold scientists say we should aim for.

Second, Loris made the case that humanity will only begin to see the truly catastrophic effects of climate change when we hit 4 or 5 degrees C. “If you have the 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius, those catastrophic scenarios really go away,” he said. In an October report, The U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that 2 degrees of warming would result in what many referred to as “climate genocide.”

When Republican Representative Doug Lamborn of Colorado asked Loris what would happen if one of the Democratic candidates running for president actually made it to the White House and instituted a ban on drilling on public lands, Loris rehashed a talking point Trump used in his “environmental address” last week. It doesn’t matter which warming scenario you use, he argued, given the global nature of climate change. In short, Democratic candidates should abandon their public lands proposals because countries like India and China are emitting more CO2 than the U.S. anyway.

Green groups weren’t convinced by Loris’ logic. “Entire small island nations along with vulnerable communities around the world, not to mention the world’s top scientists, would beg to differ with the suggestion that the difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees C of warming is inconsequential,” David Turnbull, communications director for Oil Change USA, told Grist.

“12.6 million Americans* live within half a mile of an oil or gas well and all of the pollution that comes along with that,” Andrew Grinberg, special projects manager for Clean Water Action, said in an email to Grist.

This article has been updated to reflect the fact that 12.6 million, not 17 million, Americans live within half a mile of an oil or gas well.