Vietnam wants to build a massive number of coal plants. But a former United States secretary of state is offering the country a cleaner path forward.

John Kerry is working with the Vietnamese government on an alternative to its coal plan — one that could provide the same amount of electricity, but with hydroelectric dams and solar panels instead of fossil fuels. It’s a scheme that would save the country billions of dollars, prevent pollution-related deaths, and keep greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere.

Hints of this effort have surfaced in the Vietnamese press, but a representative for Kerry said he was not ready to speak about his efforts on the record. However, the former presidential candidate discussed his work last week at the Clean Energy Finance Forum held at Stanford University. While remarks made at the forum were initially off the record, Stanford’s Precourt Institute for Energy subsequently posted a video online of Kerry’s chat with Anne Finucane, a Bank of America vice chairman. (Update: Since Grist published this story, Stanford has taken down the video featuring Kerry and Finucane.)

Kerry’s work with Vietnam started when he was secretary of state under President Obama, and it has continued into President Trump’s administration. At the forum, Kerry said Trump didn’t appear likely to embrace efforts to stave off climate change, so he figured, “I’ll try to do some back channel diplomacy.”

To pull this off, Kerry needs to get the money right. If he can convince investors to buy into his plan, it could make the clean energy alternative affordable to Vietnam. But renewable energy projects are often considered untested, risky investments — especially in less developed countries. So Kerry and the experts assembled at Stanford have figured out some ingenious methods to squeeze the risk out of these deals.

The centerpiece of the Stanford conference was a new report laying out the ways we might find the $2.3 trillion the International Energy Agency says we need to invest each year to make a transition to clean energy. That’s a lot of money — three times the amount the world is currently spending on everything from smart grids to zero-carbon power plants to energy efficiency.

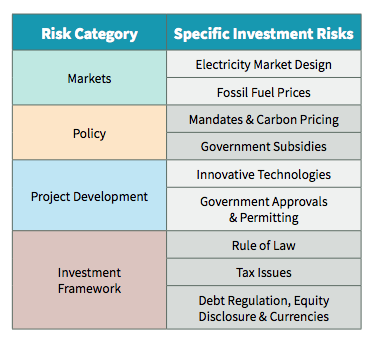

The risks associated with renewable energy projects are legion: Corrupt officials siphon away revenue, warfare halts the construction of dams, drawn-out government reviews stall proposed solar farms, newer technologies (like advanced nuclear plants) always seem to go over budget, and big swings in the price of fossil fuels make it hard to predict if any of these cleantech projects will ever turn a profit.

So many clean energy investment risks! Reicher, Brown, and Fedor

So how do you — in the jargon of the global finance bigwigs gathered at Stanford — “de-risk” these projects and draw in more investment money? Well, the report details the possible solutions, and Kerry’s strategy for Vietnam offers a good case study that could become a proof of principle.

Vietnam is planning to build a more than $120 billion electrical system in the next 20 years. And foreign corporations are already investing billions to build coal plants there because they know how to make money in the dirty energy business.

Kerry’s proposal to build solar plants, dams, and a smart grid isn’t the tried-and-true formula that makes investors feel comfortable. So he wants to put together a deal that will allow Vietnam to tell private investors that, if anything goes wrong, they get paid first. That means someone would have to agree to get paid last — philanthropies and the World Bank could take this role and shoulder the riskiest portion of the investment, leaving a lower-risk pool that would draw in money from the open market.

Under this kind of scheme, investors would bid for the chance to buy into lower-risk pools. That competition will entice private investors to offer Vietnam lower interest rates on the money they could use for these projects, saving the country “tens of billions of dollars,” Kerry said.

In return, political leaders could ask that developing countries make reforms to ensure transparency in the way their countries do business. “We can go to these countries and read them the riot act at the highest level of political leadership,” Kerry said. “Say, ‘Hey, we’re prepared to help you develop. But you’re going to have to provide the following guarantees, and they are going to have to be ironclad.’”

If this arrangement works for Vietnam, it could spread to other countries. Then the money faucets will open up, according to Kerry. “It’s going to be the private sector that solves it,” he said. “And it’s going to solve it because it wants to make money.”

While Kerry is leveraging his status as a well-connected individual to try out his experiment with Vietnam, he noted that governments should also be working to make these investments less risky. Some of the methods for de-risking clean energy are familiar to greens: A carbon tax would sure help. So would cessation of fossil fuel subsidies. Cutting the red tape required to build new clean energy plants would make things easier. And spending more money on energy research definitely wouldn’t hurt.

But as we’ve learned, what seem like fairly simple tasks to the common, environmentally minded citizen — or even the failed presidential candidate — can be a big lift for governments.