The Nomadic Museum … wandering the globe.

Photos: Gregory Colbert.

Over the next few months, hundreds of thousands of animal lovers, art lovers, and the odd Bill or Billy or Mac or Buddy will take a left off Santa Monica Boulevard and head down toward the Nomadic Museum, an extraordinary structure made entirely of reusable and recyclable materials by the Japanese architect Shigeru Ban. With shipping containers for walls and brown paper beams for columns, the museum rises above Santa Monica Pier like a modern-day cathedral — complete with a vaulted ceiling, dim lighting, and horrible insulation.

The building is a destination in itself, but its main purpose is to house “Ashes and Snow,” an exhibition of the animal photography and film work of Canadian artist Gregory Colbert. Inside, Colbert’s photos hover on both sides of a long center aisle, facing inward like the stations of the cross. At the end of the aisle, where the altar would be, a large screen plays an hour-long black-and-white film on repeat.

“Ashes and Snow” installation.

As its name suggests, the museum — like the exhibition itself — was built to travel. “Ashes and Snow” first opened in New York last March, and after a five-month stop in Santa Monica, it will move on to Paris, the Vatican, and Beijing, with other potential stops in port cities around the world. Millions of people will eventually see “Ashes and Snow.” But if you don’t happen to be one of them, never fear: Colbert’s photos will soon be coming to a cubicle near you.

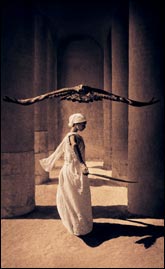

Like the museum, Colbert is something of a nomad whose explorer-cum-artist lifestyle seems like a throwback to another era. He has spent the last 13 years traipsing across the globe filming and photographing the world’s more majestic animals in highly choreographed interactions with humans — dancing, sleeping, swimming, flying. His spare, black-and-white photos are printed on large sheets of handmade Japanese paper and tinged in sepia. In one, a small herd of elephants slowly rises up from a dark lake while a canoe carrying two shawl-wearing passengers floats by. In another, an old woman and young boy sit atop a sand dune, barely clothed; beside them sits a cheetah at attention. In a third, an eagle flies through a temple colonnade while a young woman dances beneath it.

Your first thought is “Photoshop,” but Colbert insists he doesn’t manipulate his images. Thanks to deep-pocketed funders (after his last exhibition in Venice, the chair of Rolex bought the entire show), he has all the time in the world to wait for the animals to behave and the lighting to be perfect. Technically, it’s something of a marvel; as a project, it’s something of a disappointment.

Ashes to Ashes

“Ashes and Snow will reawaken in us an understanding of our shared animal nature,” the exhibition’s literature reads. “The insight will affect the way we behave in our environment and help us find the empathy and wisdom to interact peacefully in a world that was once one.” And yet the world Colbert creates in many of his photos is not that much different from the one we live in already, with humans at its center forcing animals to bend (and bow and dance and fly) to our will. The artist’s nostalgia (was the world “once one”?) elides that most fundamental of contradictions: we love, admire, and even worship our animals — and then we destroy their habitats and kill them.

There’s nothing wrong, per se, with using animals to excite our nobler ideals. Elephants and whales, birds of prey and big cats, all possess qualities so extraordinary that we are continually gobsmacked by their very existence. Since earliest recorded history, animals have been the subject of art (think Altamira or Lascaux), and humans have always made the rather wonderful imaginative leap of ascribing other powers to these animals as well — powers of healing, wisdom, magic. Indeed, animals are part of the iconography of nearly every religion. Likewise, the beauty and quasi-divine mystery of wild creatures have been important themes of the environmental and animal-rights movements, which have used these qualities to promote veneration and protection.

But the preservation of species is as much a practical issue as an aesthetic or religious one, and locating animals squarely in the spiritual realm separates them from their very real, very earthly, very endangered habitat. The challenge for an artist like Colbert (and the same could be said for environmental and animal-rights activists) is to explore the wonder inspired by the natural world without falling into the trap of sentimentality or exoticism.

That is a tall order, not least because animals have long been a problematic subject for artists. There’s not a lot of space in the contemporary Western art scene for animal-themed art that is both aesthetically and politically meaningful. National Geographic has cornered the market on breathtaking images of animals in the wild — and, in so doing, has occasionally earned the scorn of serious artists and the suspicion of many critics of social relations. Meanwhile, well-known contemporary artists who have featured animals in their work, such as Sally Mann or Damien Hirst — or even William Wegman, whose sense of irony Colbert could learn from — must weather the ire of animal-rights activists and charges of sentimentality from critics.

Unsurprisingly, then, many of the reviews of Colbert’s work have been vicious: “vacuous” and “insipid” are just a few of the epithets that have been used to describe the show. Writing for The New York Times, Roberta Smith called the exhibition “an exercise in conspicuous narcissism that is off the charts, even by today’s standards.”

While it’s safe to say that this particular piece of Smith’s criticism is equally “off the charts,” her general point — that it’s important to think about what these pictures are actually saying and not just be seduced by their prettiness — is well taken. Colbert talks about creating new myths that will reconnect humans and animals, but the way he tells his tales is disturbingly familiar. Besides being anthropocentric (or, more accurately, Colbert-centric), his photos harness a hackneyed visual language of purity: black and white, sepia tones, classical settings, the church-like exhibition space. His animal subjects only include those that come with superlatives attached: biggest, fastest, strongest. (Nary a titmouse in this temple.) His aesthetics give meaning (perhaps for the first time) to the palindrome, “Meet animals. Laminate ’em.”

Brand Slam

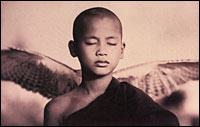

And it gets worse: In pairing his animal-gods with the likes of praying Buddhist monks and Africans in native dress, Colbert marries his wall-calendar aesthetic to a rather oblivious brand of exoticism. (And it is a brand: One image, of a pretty young South Asian woman dancing with elephants, is so reminiscent of Richard Avedon’s fashion shot Dovima With Elephants that Colbert should worry about a lawsuit.) His people are less people than pinups, and the same goes for the animals themselves. In some ways, these elephants and cheetahs are no different from dancing bears.

Perhaps that’s why the images of Colbert himself swimming underwater with sperm whales off the coast of Tonga are the most moving in the show: for once, the artist is not completely in control. Without a breathing apparatus, a stranger in the whales’ natural environment, he finally achieves the effect he says he’s going for — the respectful, awesome contemplation of how we all fit together in the world. The result is at once disorienting and sublime. In a similar way, Colbert’s film, which glides effortlessly between species and continents, achieves a meditative quality that is, at times, transfixing.

Alas, those images are the exception: a good amount of Colbert’s work suffers not only from cliché and exoticism, but also from an overdose of cuteness. His writings and interviews are full of psycho-spiritual babble and pseudo-profundity. (“Nature doesn’t have a style, it has a voice.”) Thinking people don’t need to be lectured about the majesty of animals, or fed images of young Asian boys reading to elephants — as if there’s some secret wisdom that only Asian boys and elephants share.

When dealing with the natural world — as when dealing with so much in life — we must be able to handle competing realities: the political, spiritual, emotional, and intellectual; the practical and the ideal. Great artists relish the tensions between these realities and manipulate them to create a new way of seeing the world. Colbert’s art takes an easier path, borrowing its profundity from the tired icons of old and the easy consolations of religion. Would that he had filled his modern-day cathedral with ideas worth thinking about after the hour of worship was over.

“Ashes and Snow” is on exhibit at the Santa Monica Pier in California through May 14, 2006.

Discuss this story.