A massive, bipartisan clean water infrastructure bill passed the Senate 89-2 on Thursday. The Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Act would create a $35 billion fund for states and tribes to improve water systems — 40 percent of which would go to underserved, rural, and tribal communities.

The legislation would fund projects that address aging infrastructure and improve water quality, remove lead pipes from schools, and update infrastructure to be more resilient to the impacts of extreme weather and climate change. The bill, having passed the Senate, will now move to the House of Representatives.

Such an influx in funding for America’s aging water systems is long overdue, policy experts, environmentalists, and urban planners argue. A 2018 study of 30 years of data found that in any given year, as many as 10 percent of community water systems in the United States have health-based violations, affecting up to 45 million people annually. In addition, more than 2 million Americans live without access to drinking water and sanitation services — such as safe drinking water, plumbing in the home, and wastewater removal and treatment — according to a 2019 report by the U.S. Water Alliance. Native American households are 19 times more likely to lack plumbing than white households; Black and Latino households are nearly twice as likely. Race is the strongest determinant of whether or not a household has access to water and sanitation services, the 2019 report found, the result of a history of racist policies in the planning and construction of water infrastructure.

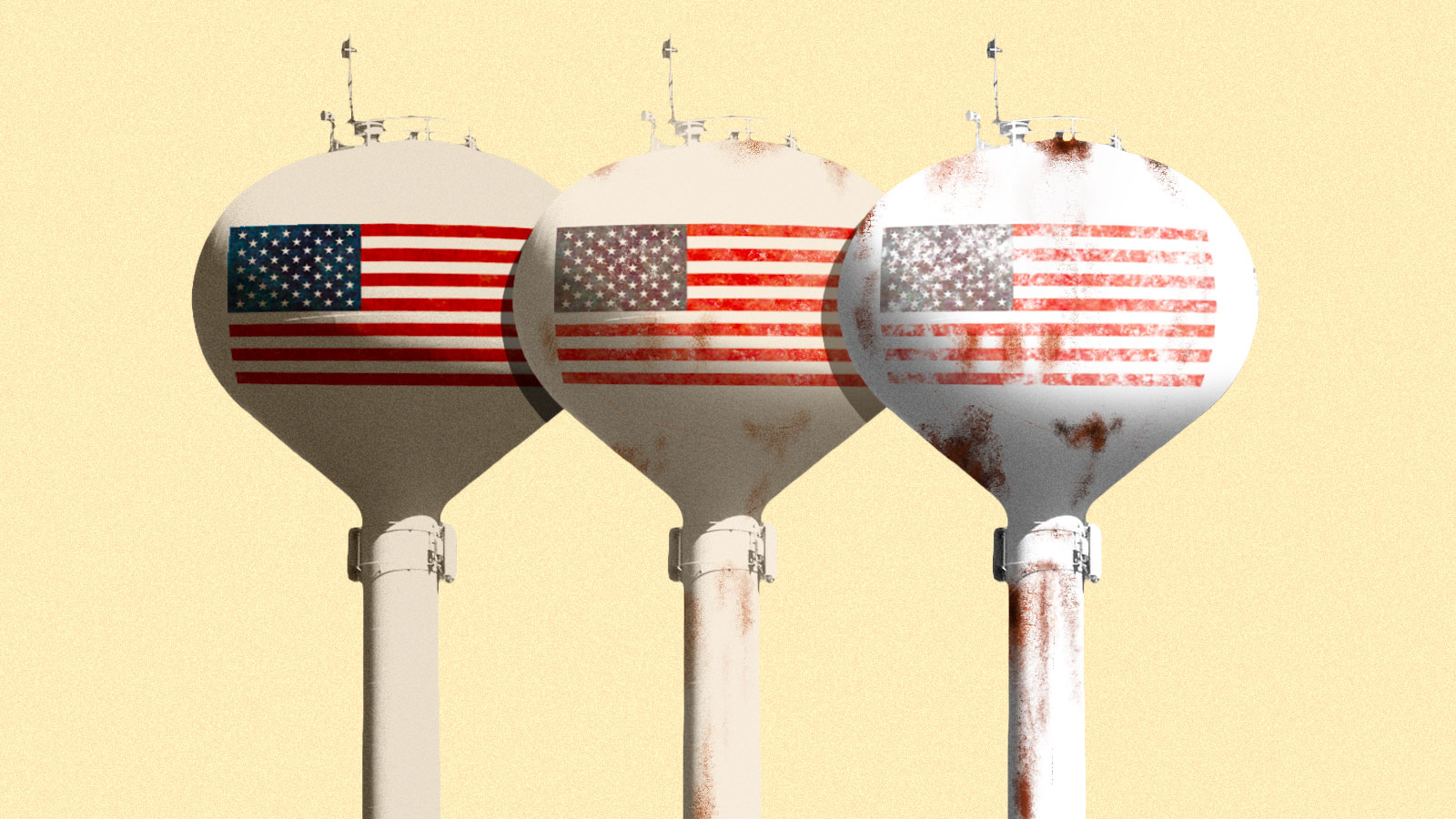

While federal funds for water systems were plentiful following the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Water Act in the 1970s, federal investment has declined dramatically, from 63 percent of capital spending in the water sector in 1977 to just 9 percent in 2017. This has produced a towering annual investment gap — one that is estimated to grow to $434 billion nationwide by 2029, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Tribal systems have been particularly underfunded: In 2016, the Indian Health Service estimated that $2.7 billion would be required to provide access to safe and adequate water and sanitation services. Nearly half of maintenance on American water systems is done reactively, meaning after they have already failed because of deferred maintenance or investment. The American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2021 report card gave the country’s water infrastructure a C grade overall.

“Access to clean water is a human right,” said Senator Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, who introduced the new Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Act. “Every American deserves access to clean water no matter the color of their skin or size of their income.”

Investments in water infrastructure can often be a hard sell politically. “A lot of these are invisible investments. Distribution networks are underground, people can’t really see them,” said Maura Allaire, professor of urban planning at the University of California, Irvine. “It can be really hard to invest — until a catastrophe happens.” The Biden administration is aiming to fill some of the existing gap as a part of the American Jobs Plan, which promises $111 billion for water systems. The administration praised the new act, saying in a statement that the bill “aligns with the administration’s goals to upgrade and modernize aging infrastructure.”

If approved by the House and signed into law, funding from the new bill would come in incremental increases to state water infrastructure budgets from 2022 to 2026. The bill also earmarked $50 million annually for tribal water systems and $100 million per year to remove lead drinking water pipes from schools. The bill also promotes investments in projects that would make drinking water systems resilient to extreme weather events and climate change.

Some say that while the bill is a significant step in the right direction, it may still not be enough. “This bipartisan legislation is an important first step to ensure communities impacted most by old and inadequate water infrastructure receive the investments their communities have been owed for decades,” Julian Gonzalez, legislative counsel for the environmental group Earthjustice, said in a statement. “While this legislation is a great start, it cannot be the final investment in communities that have been in peril even before the COVID-19 pandemic further devastated them.”