Owens Lake, on the eastern flanks of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in southeastern California, was, at its peak, a 200-square-mile perennial lake. Located at the terminus of the Owens River, it held water continuously for at least 800,000 years. It is now an extreme example of the destabilizing effect of surface-water extraction in desert regions.

Beginning in 1913, the Owens River was diverted to bring water to the city of Los Angeles, and by the mid-1920s Owens Lake was dry. For decades, the lake’s dry bed produced enormous amounts of windblown dust. Indeed, it became the single largest source of particulate-matter pollution in the United States, by one estimate emitting almost a million tons annually. The dust contains carcinogens such as nickel, cadmium, and arsenic, as well as sodium, chlorine, iron, calcium, potassium, sulfur, aluminum, and magnesium.

During dust storms, air pollution around the dry lake bed has reached 25 times the level acceptable under national clean-air standards. The dust travels both north and south on turbulent winds channeled through the Owens Valley by the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the west and the White-Inyo Range to the east; the toxic dust has been tracked by satellite some 155 miles to the south into the Los Angeles area.

The city of Los Angeles owns thousands of acres of Owens Valley lands, along with the rights to the water in the Owens River. (Remember the movie Chinatown?) The river still flows through the upper part of the valley, but is then diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct 51 miles upstream from the point where it used to enter Owens Lake.

Under California law, the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District has been given the authority to order Los Angeles to undertake reasonable measures to mitigate the air-quality impacts of its water-gathering activities. In 1998, after decades of legal wrangling, the city began implementing dust-control measures to abate the toxic dust storms that come off the barren lake bed. These controls include the shallow flooding of thousands of acres along the eastern edge of the lake with a small percentage of the water that is diverted, as well as reclaiming some of the saline lake-bed soils and establishing fields of salt-tolerant grass irrigated with hi-tech buried drip systems. Los Angeles continues to implement these dust controls and will complete the $400 million project by the end of 2006.

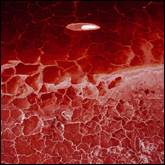

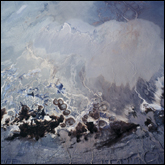

The Lake Project comprises my aerial images of Owens Lake, taken between 2001 and 2004. Viewed from the air, vestiges of the lake appear as a river of blood, a microchip, a bisected vein, or a galaxy’s map. It is this contemporary version of the sublime that I find compelling. In The Lake Project, the lake has become the locus of water’s absence. The lake is a negation of itself, a void. To grow the city of Los Angeles is to deplete, starve, or implode the body of water that was once Owens Lake, so The Lake Project images serve, in a sense, as the lake’s autopsy. In nearly every image from The Lake Project, water is harnessed for some use, and in the process it is in some manner manipulated or destroyed, its presence denied. This is not to say that it has been stripped of its inherent beauty. But its beauty has been subjugated by its use, and while its physical condition may be thrilling to behold — water in shades of red, green, amber, and purple — it is a beauty born of environmental degradation. There is a sense of both seduction and betrayal with these images, and the viewer is ultimately complicit in their absorption by this toxic site.

This past fall, I was commissioned by SF Camerawork (a nonprofit arts organization in San Francisco) to create a public art piece consisting of 12 billboards which focused on The Lake Project material, as part of their current exhibit “Monument Recall: Public Space and Public Memory.” The billboards and links to further material on the history and the demise of Owens Lake can be found at lakeproject.org. In addition, an oversized monograph book, The Lake Project, was released this fall by Nazraeli Press, with an introduction by the curator Robert A. Sobieszek of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Click here to start the slide show.