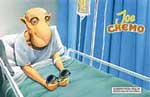

Maybe you’ve seen Adbusters magazine or the Adbusters website, with their takeoffs on common ads. “Joe Chemo,” the popular Joe Camel, sits sad, sick, and bald in a hospital bed. A sports utility vehicle surges through the wilderness under the slogan: NATURE — IT’LL GROW BACK. A slumped over vodka bottle proclaims ABSOLUTE IMPOTENCE.

It doesn’t take much artful ridicule like that to undo billions of dollars worth of careful product positioning. Which, of course, is the intent. Adbusters was founded by Kalle Lasn and friends, many of them soul-sick dropouts from the advertising industry.

Lasn, born Estonian, now Canadian, seems to run on a high-test mixture of humor, creativity, and rage. His organization hands out bright McDonald’s-red stickers saying GREASE, each of the E’s a sideways golden arch. You can stick them onto trays and things at fast-food restaurants. He promotes Buy Nothing Day, the last Friday in November, now celebrated (very unofficially) in dozens of nations and languages.

Lasn is having fun and is deadly serious at the same time. His critique of the consumer culture, which he has just set down in a book called Culture Jam, is a strange combination of hilarious and furious — furious at the way marketing has taken over the world.

You reach down to pull your golf ball out of the hole and there, at the bottom of the cup, is an ad for a brokerage firm. You fill your car with gas, there’s an ad on the nozzle. Your kids watch Pepsi and Snickers ads in the classroom. You pick up a banana in the supermarket and there, on a little sticker, is an ad for the new summer blockbuster at the multiplex. Coca-Cola strikes a six-month deal with the Australian postal service for the right to cancel stamps with a Coke ad. A company called VideoCarte installs interactive screens on supermarket carts so you can see ads while you shop.

He is appalled that we put up with all this. “Corporations, these legal fictions that we ourselves created two centuries ago, now have more rights, freedoms, and powers than we do. And we accept this as a normal state of affairs. We go to corporations on our knees. Please don’t cut down any more ancient forests. Please don’t pollute any more lakes and rivers (but please don’t move your factories and jobs offshore either). Please don’t use pornographic images to sell fashion to my kids. Please don’t play governments off against each other to get a better deal. We’ve spent so much time bowed down in deference, we’ve forgotten how to stand up straight.”

Poster design: Jonathan Bambrook.

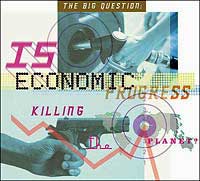

So Lasn is fomenting a revolution. Every time a G-7 summit brings together the leaders of the seven largest economies, he plots ways to get reporters or citizens or billboards in the host city to ask them, “Is Economic ‘Progress’ Killing the Planet?” He makes “uncommercials” that promote TV Turnoff Week or the demise of the automobile. When the networks refuse to sell him time to air them, he makes headlines by asking why corporations can buy ads but citizens can’t. What happened to freedom of speech?

Lasn envisions the revolution proceeding through a wave of grassroots Gandhian noncooperation. His book provides dozens of suggestions of ways to join in the fun.

Instead of standing silent and submissive in a long line at the bank, we could say loudly but politely to no one in particular, “Why can’t this bank hire enough tellers?”

When we find an unsolicited ad on our fax machines, we can fax back a black sheet of paper (which drains the toner of the receiving machine) with a small white window within which is the message, “don’t fax me ads.”

When a phone solicitation comes at dinnertime, we can say we’re busy right now, but if we can have the caller’s home number, we’ll call back. When he or she refuses, we say, “You called me at home; why can’t I call you at home?” Or alternatively we can interrupt the spiel. “Before we go any further, you should know that I bill my time at $60 an hour. If you want to talk to me it will cost your company a buck a minute. Time starts now.”

If the college hockey team requires us to wear a jersey with a Nike swoosh on the front, we can organize our teammates, call a press conference, and refuse to become human billboards. We can recognize that walking around wearing corporate logos marks us not as cool, but as tools.

We can insist that a corporation that repeatedly breaks the law lose its corporate charter. Three strikes and you’re out.

Rosa Parks won’t go to the back of the bus. An anti-Marcos rioter in the Philippines puts a flower in the barrel of a policeman’s rifle. A Chinese dissident dances in front of a tank at Tiananmen Square. “A gesture like that becomes a metaphor, living forever,” says Lasn. “One day soon people will get sick of fast food, fancy cars, fashion statements, and shopping malls. They will stop buying heavily advertised products because advertising is coercive, tawdry, and just increases the cost of the product. And our children will gaze back aghast upon our own time, a period of waste and abandon on a scale so vast it knocked the planet out of whack for a thousand years.”