This is part of a series of interviews with presidential candidates.

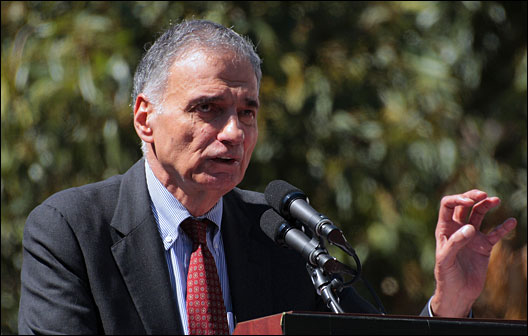

He brought you the seat belt. He launched a consumer advocacy empire. He got 2,883,105 votes in the 2000 presidential election, which critics argue helped put George W. Bush in the White House. Ralph Nader has earned fame — and infamy — for many doings over his 40-plus years as a firebrand activist. Perhaps less well-known is his contribution to environmental protection in the U.S.

Nader, who entered the 2008 presidential race in late February, was on the frontlines of environmental advocacy in the 1970s. He went to bat for the first auto fuel-economy regulations and was a major voice against nuclear-power development. He fought for the passage of cornerstone environmental laws including the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. In the years since, he’s pressed on with green advocacy, publishing numerous studies, essays, and editorials decrying coal and nuke power and advocating ultra-efficient cars and a solar-powered economy.

But for all his work in these areas, Nader has done little so far to flesh out an environmental and energy platform for his presidential campaign. The only specifics on his campaign website are that he supports solar energy and a “carbon pollution tax” and opposes nuclear power. To rustle up some particulars, I called Nader on his cell phone as he journeyed from one campaign stop to the next.

For more info on his environmental stances and record, check out Grist’s Nader fact sheet.

Why should voters consider you the strongest environmental candidate?

I was a big advocate of renewable energy back in the ’70s — all forms, from wind power to photovoltaic to solar thermal to passive solar architecture. I was a very early opponent of nuclear power. As a lobbyist, I was instrumental in the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, along with legislation to control air pollution and other toxic substances. I was also involved in the passage of the first motor-vehicle efficiency laws back in the ’70s. So my words on this issue as a candidate reflect what I’ve done, rather than what I hope to do.

Going forward, what sets your environmental platform apart from the other candidates’?

I’m basically promoting a massive conversion from a hydrocarbon-based economy to a carbohydrate-based economy. I’m not talking about corn ethanol, which has a very poor net energy- and water-usage characteristic. I’m talking about industrial hemp. I’m talking about plant life that can be efficiently converted to fuel — like sugar cane, agricultural waste, cellulosic grasses, and certain kinds of biomass that can be grown with a spectacular ratio of energy inputs to outputs. I’m talking about a very fundamental remodeling of our economy — a conversion from industrial-age, 19th-century technologies like the internal combustion engine to renewable, sustainable technologies of efficiency and production. We should have vehicles that get well over 100 miles per gallon. As Amory Lovins and Paul Hawken have shown, we can create far greater efficiencies in the use of our natural resources, whether it’s copper, iron, oil, gas, timber, you name it.

Let’s get more specific about how you would implement this massive shift. You propose a carbon pollution tax, for instance. How would that work?

You tax inefficient technology and you tax pollution. The carbon tax would not be a credit exchange [as in a cap-and-trade program], which can be easily manipulated. It would be a straight-out tax on hydrocarbon production at the production source — where it’s far, far removed from consumers and forces better choices of technology from the get-go.

Would energy producers then pass an increase in prices along to consumers in the form of higher gasoline and electricity prices?

Not necessarily, because it will provide a competitive opportunity for companies to say, “Hey, it’s now more expensive to produce polluting technology than it is to produce non-polluting technology.” And they will begin to break ranks from one another in an effort to innovate, and the magnet will be toward the more efficient option.

To protect consumers, you could have an excess profits tax on companies such as Exxon, and rebate it back to the customer. Or we could use the proceeds from the pollution tax to build more alternative public transit — that would relieve the burden on consumers.

Some people argue that a carbon tax is political suicide because you can’t make taxes appeal to voters, period.

Look, this is not a gasoline tax. This is not a final product tax that directly hits consumers. It’s a tax at the coal mine, a tax at the oil well.

Your website says, “No to nuclear power, solar energy first.” How do you plan to phase out nuclear and phase in renewables?

Oh, this is easy. The first thing you gotta do to stop nuclear power is prevent government guarantees of Wall Street loans to nuclear power companies to build plants. They will not get private-sector financing without a 100 percent Uncle Sam guarantee. You appeal to conservatives and liberals who don’t like corporate welfare and say, “Let’s stop rigging the playing field and cut off loan guarantees to nuclear power.”

As far as the renewables are concerned, you can do it in two ways: You can basically eliminate all direct and indirect subsidies to fossil fuels and nuclear and say, “Let’s have a level playing field.” Or you could actively increase tax credits and subsidies to solar power because it has superior environmental and geopolitical benefits. Furthermore, the government’s a big customer — it can take its entire procurement power and direct it toward solar energy and sustainable technology.

Keep in mind that we’re currently paying six, seven dollars a gallon for gasoline if you include all the military expenditures to safeguard the global oil pipeline. That’s something that taxpayers are paying for, even if it doesn’t show at the pump.

Nuclear makes up 20 percent of America’s electricity supply. Coal makes up more than half. Would you phase out coal as well, or do you believe in the promise of advanced coal technology?

There’s no such thing as clean coal. Anybody who’s been down in a coal mine knows that. You’ve got to phase out all fossil fuels: first coal and oil, then natural gas.

How quickly would you phase out fossil fuels?

If we had the will, we could convert most of [the infrastructure] in 20 to 25 years, and that includes a significant portion of the housing and building stock, which you’ll replace with different types of structures and solar architecture, and retrofit existing buildings for solar water heating and photovoltaic.

I think solar energy is on the verge of exploding in this country. California is adding jobs by the day. The beauty of solar energy is, the jobs it adds are very decentralized, right down to “fix it yourself” firms in little towns. It’s wonderful for climate, it doesn’t promote wars abroad, and we’ve got a 4-billion-year supply. And Exxon cannot eclipse the sun in order to produce a shortage.

Do you see renewable energy costing consumers more than conventional electricity?

If you include the costly military and environmental externalities of fossil fuels and nuclear, solar has been cost-competitive for years. If you exclude the externalities of finite fuels, wind power is already competitive, passive solar architecture is competitive. Meanwhile, the price of photovoltaics and other forms of solar-generated electricity are coming down very fast every year, and are on an upward curve of innovation — with new technology, refined ways of producing the film, etc. They will be uniformly competitive within the next 10 years.

Remember that consumers are paying [for today’s energy system] in many other indirect ways: strip mines, acid runoff into lakes and streams, pollution in their lungs, medical costs. Sixty-five thousand people a year die from air pollution, half of them from coal-burning utility plants. Those are just a few of the external costs operating here.

Would you use revenues from your carbon tax to provide incentives and tax breaks for renewable innovation?

Industry argues for public subsidy, but I think renewable energy technologies are moving very, very fast toward a competitive posture with fossil fuels. It’s happening on its own. That’s even without accounting for the horrendous external cost, military cost, pollution, health cost, and damage to land and water. Once you’ve incorporated all of those burdens, the cost comparison is not even close. If the geopolitical and environmental costs are so compelling, government tax credits can reverse the uneven playing field that has existed for decades to the advantage of fossil fuels and nuclear, and direct them toward solar consumers and the fledgling solar industry.

Companies from Wal-Mart to GE have been launching green initiatives and building clean energy solutions. What do you think of these efforts? Do you see corporate America today as a breeding ground for transformative change?

Oh yeah. Why not? I mean, when they start competing over light bulbs and things like that, that’s a sign the solar age has come of age. After General Electric monopolized and stagnated the electric light bulb for decades, costing billions of dollars and many, many megawatts of waste, it’s nice they’ve finally recognized that consumers want efficient lighting systems.

Many argue that the U.S. shouldn’t commit to a global greenhouse-gas reduction target that doesn’t involve China and India. Do you agree with this? How would you bring them to the table?

You bring them to the table by restricting imports of badly emitting greenhouse-gas technologies. Then you devise an international treaty where you analyze very carefully which countries really need aid in this area, which countries don’t need aid, and you proceed accordingly. You have a deliberative process under an international body with a global goal of restricting greenhouse gases and acid rain and other things.

What do you think is the most important environmental issue we face after climate and energy?

It’s all about solar, in all its manifestations — from passive solar to active, including photovoltaics, solar thermal, and efficient biomass [plant life fed by sunlight]. Wind is also a form of solar energy, because the sun creates the earth’s climate, including the winds within it. Solar is the greatest universal solvent for environmental hazards.

What do you think of Al Gore’s climate activism? Has he been an effective agent of change?

At last. Where was he when he was vice president? We couldn’t get him to make a speech on solar energy. But now, like Martin Luther King Jr. said, he’s “free at last, free at last,” and he’s made a major contribution.

Many have called George W. Bush America’s worst environmental president, and some critics have said that if you hadn’t entered the 2000 race, Gore would have been president, and therefore Bush’s irreversible environmental damage never would have happened.

Well, tell those critics to take a course in elementary statistics and engage all variables, each one of which would have put Gore in the White House. Gore won, but the Republicans stole his victory in Florida. The Electoral College stole his victory nationally after he won the popular vote. The Supreme Court stole his victory. And 250,000 Democrats in Florida voted for Bush. We’ve got to stop playing the spoiler game and treating third-party candidates as second-class citizens.

If you’re going to blame me for Gore’s loss — and Gore doesn’t blame me, by the way — then you’ve got to credit me for Gore’s Nobel Prize for his alerting the world to global climate change, for all of his successes with books, and for his millions of dollars of appreciating Google stock.

Maybe you should get an honorary percentage. On to another topic: Who is your environmental hero?

There are several. One is David Brower. Another is Barry Commoner, who wrote Making Peace With the Planet, among other great books on the environment. The third one is Amory Lovins.

What was your most memorable wilderness or outdoor adventure?

Camping in Yosemite National Park when I was as a student at Princeton. I thought it was the most beautiful place on earth, in spite of the haze from 25,000 vehicles in the valley below.

If you could spend a week in one natural area of the U.S. now, where would it be?

The Green Mountains of Vermont.

What do you do personally to lighten your environmental footprint?

I consume very little except newspapers, and I recycle them. I don’t have a car. I’m the antithesis of the over-consumer.

How are you getting around for your campaign?

We use planes and cars and trains. When we get there, we spend very few resources in getting our message across.

Are you going to offset your footprint from the planes and cars?

I think that’s an indulgence. I don’t trust these offsets. We can do a lot more than that.

If George Bush were a plant or an animal, what kind of plant or animal would he be?

Poison ivy. As for an animal, I wouldn’t demean any animal species that way. It’s easy to say coyote, but that’s a stereotype of animals. What carnivore has ever, as a species, done what Bush has done to the Iraqis?