Swati Prakash is environmental health director for West Harlem Environmental Action (WE ACT), a nonprofit, grassroots organization working to improve environmental quality and to secure environmental justice in predominately African-American and Latino communities.

Monday, 1 Oct 2001

NEW YORK, N.Y.

Monday morning. My first thought as I go through my morning ritual is, “Will this week see New York returned to ‘normal’ (whatever that means)?” It’s been almost three weeks and from my perspective, living and working all the way uptown, life has been slowly settling back into a slightly awkward version of “before.”

I live in West Harlem, at the northern end of Manhattan. I take the bus to work in the morning, past one of the six diesel bus depots located in northern Manhattan and within two blocks of another one of those depots. My morning commute also takes me past smaller diesel bus and truck depots, the North River Sewage Treatment Facility, and several dozen auto body shops, dry cleaners, and other chemical-intensive small businesses. It is also a ride through one of the most vibrant and culturally rich communities I have ever lived in. I pass several public schools, including the former Harlem School of the Performing Arts, the City College of New York, a community swimming pool, multiple day-care centers, several tiny parks and backyard gardens, and four high-density public-housing developments. The bus cruises along block after block of beautiful old brownstone apartment buildings. Like many lower-income urban communities of color, this is a community of contrasts, where some of our most valued and vulnerable assets exist side-by-side with sources of pollution.

Our office is located almost adjacent to the Apollo Theater (rumored to be the most frequently visited tourist attraction in the city of New York) on 125th Street, a historic and bustling retail thoroughfare.

Sitting at work today, I’m thinking about how and when we are going to reschedule our national conference on “Human Genetics, Environment, and Communities of Color: Ethical and Social Implications,” which was originally slated to take place here in New York City shortly after the terrorist attacks. On the Friday after the World Trade Center was destroyed, we had to make the difficult decision to postpone our conference; now it’s time for me to set the new date.

I have been planning this conference since this time last year. How does an environmental justice organization come to organize a national conference on genetics and communities of color? We initially approached the issue through our experience with conducting and promoting research on environmental health concerns in communities of color. Environmental health researchers are increasingly investing resources into understanding the genetic basis for vulnerabilities to environmental toxins, in the belief that this knowledge could lead to the development of improvements in environmental health. At the same time, some environmental and health advocates have expressed concern that growing attention to the genetic factors could divert attention and resources away from efforts to reduce exposure to toxins. Another concern is that this research could subtly shift the perception of who is responsible for environmental health problems from polluters to the individuals living in polluted environments.

The idea for the conference came about last year when we realized that genetics research is likely to affect the work we do as environmentalists and as people of color. It seems important that environmental justice activists have at least a working understanding of the state and nature of research in the field of genetics, and that we have some forum for expressing ethical and social concerns. Now the conference will have to wait until some time in March.

11 a.m.: My phone rings. “I need help,” says a woman who identifies herself as the parent of a child in a public elementary school located a few blocks from the World Trade Center site. She tells me that although the school remains closed, there is talk of sending the children back in a few weeks. She is concerned because independent tests conducted by a contractor near the school have found high levels of asbestos (2 to 3 percent) in dust — still more data to add to the environmental puzzle emerging from the WTC disaster. I know the U.S. EPA has been monitoring air and dust for asbestos, and reassuring the public that the levels it has found are safe. There are also on-going clean-up efforts, including 10 giant HEPA (High Efficiency Particulate Air) filter vacuum trucks that have been brought in to clean up sidewalks and streets in the vicinity.

Yet this is not the first concerned person who has called me to ask if I know “what’s really going on.” I wish I knew more about what is really going on. EPA samples taken shortly after the disaster showed elevated levels of dioxin, lead, and chromium in the air. The results of more recent samples are not yet available. I’ve heard that environmental scientists from nearby universities have taken their own samples, but I know nothing of their results. In the frantic rush first to deal with the acute crisis and now to clean up the site, environmental health concerns were placed on the back burner. However, as New Yorkers attempt to return to “life as normal,” these concerns are starting to emerge. There is unmistakably something in the air still; when you walk around the downtown blocks nearest to the site (as I did over the weekend), you still catch the smell of burning metal and rubber. The questions to be answered are: Exactly what is in the air and in the dust that continues to settle to the ground, and how much of it is there? I feel challenged to find my place in assessing and evaluating actual public health risks from my community base three miles away in Harlem.

Meanwhile, the concerned mother on the phone is waiting for a response from me. She doesn’t want her child sent back to the school in a few weeks if there is still a health threat, and asks if we can help her organize to ensure that the school is truly safe enough for the children to return. I share with her what I know about EPA’s cleanup efforts and monitoring information, take her number and tell her I’ll get back to her. It is going to require some time and phone calls to track down and try to make sense of all the existing monitoring data and find out exactly what the long-term cleanup plans are for this area.

Tuesday, 2 Oct 2001

NEW YORK, N.Y.

9 a.m. Today’s thought of the morning is: “There’s no way there are enough hours in the day.” As I get into the office and look at my long list of “current activities,” I take a deep breath and tell myself “Yes, I can do this.” But it’s always good to ask for a hand. After all, I remind myself, that is a key element of our community-based research model for combating environmental racism — leveraging scientific and other academic tools to promote environmental health and justice in communities of color.

Yesterday afternoon as I sent out emails and made phone calls about environmental sampling and health issues in the wake of the World Trade Center disaster, there was a knock at the office door. A law student from a local university came in and asked if she could have some information about our organization. Drop-ins like this are common, although they are usually from community residents or area employees. It’s one of the great aspects of being located right in the middle of the community.

Department of Sanitation garbage truck depot on 99th Street in Ea

st Harlem.

Photo: WE ACT.

This student is from a community-organizing law clinic at her school. “Good,” I think. It’s always helpful to have access to legal resources, particularly from people who are sensitive to the complexities of using the law as a tool in broader community organizing efforts. I give her our brochure and a quick summary of some of our local organizing and community outreach efforts. One of the initiatives I tell her about is a tenants’ association in East Harlem that wants to get a Department of Sanitation garbage truck depot out of its backyard. The association came to us for assistance, and we are currently helping to organize a community forum. Scheduled for later this month, the forum will discuss asthma, air quality, and the impact of the diesel-producing garbage trucks. In addition to approaching us, the association asked public interest lawyers to assist with the case.

I am happy to hear that my student visitor is with a law clinic that focuses specifically on community organizing, and I’m curious to meet her professor. I’m very interested in how the law can be used as a tool to supplement broader community organizing efforts on health, environmental, and housing issues. It’s important that these legal approaches do just that — enhance community organizing efforts rather than overriding or replacing them. If legal tactics are the only tools a community has and they fail, what’s left is disappointment and disempowerment.

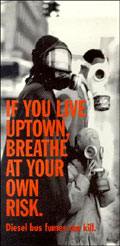

Later in the day, I get on the phone with Patrick Kinney, an air pollution scientist at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health in the Department of Environmental Health. Columbia is our university partner on several community-based research projects. Last year, WE ACT, Columbia, and the University of Southern California were jointly awarded a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to develop and teach an air-pollution curriculum focusing on pollution from traffic, particularly diesel-powered vehicles. The curriculum includes the use of a portable device for measuring fine particulates in the air — particles whose diameters are less than 2.5 micrometers, a millionth of a meter. (For comparison, a human hair is roughly 100 micrometers, or microns.) This curriculum complements the efforts of our four-year-old diesel campaign, “If You Live Uptown, Breathe At Your Own Risk,” designed to alleviate the disproportionate use of diesel vehicles in northern Manhattan.

I call Dr. Kinney to ask if he’ll speak at the East Harlem community forum on the health effects of diesel-powered garbage trucks. He agrees. We discuss the relative merits of portable devices that take real-time measurements of airborne fine particulate counts versus those that read the mass concentration of fine particulates. In other words: Do we want to know how many fine particles are in a standard volume of air, or do we want to know the combined weight of fine particles in that air?

Health-based standards, including the U.S. EPA’s new National Ambient Air Quality Standard for fine particles, are given in terms of mass concentration, read as “micrograms per cubic meter” (a microgram is a millionth of a gram). However, diesel exhaust consists mostly of really tiny particles, called ultrafines, which have diameters of less than 0.1 micron. Ultrafines are so small they hardly weigh anything, so Dr. Kinney and I decide that it’s probably better to count the particulates rather than trying to measure their mass. Still, we decide to hold off on purchasing the equipment until he talks to other scientists who have used both instruments and until I talk to colleagues about the potential policy-related benefits of measuring fine particulate mass.

Today, I focus on writing the preface to a supplemental issue of Environmental Health Perspectives on the theme of “Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Advance Environmental Justice.” This year, WE ACT submitted a successful proposal to EHP to serve as guest editor of this supplemental issue, in partnership with Mary Northridge of the Harlem Health Promotion Center at Columbia University.

Serving as guest editor meant compiling research articles and commentaries from not only environmental health scientists, but also environmental justice advocates. It meant featuring community-driven environmental health research conducted in low-income communities and communities of color by people who literally live and breathe environmental hazards. We submitted a compilation of such articles to the editors of the magazine in August, and now we have to finish co-writing the preface to the issue. The anticipated publication date is April 2002. This monograph represents a great opportunity to communicate to environmental health scientists the importance of conducting community-based participatory research (CBPR), a model rooted physically and conceptually in the community. CBPR is driven by the principle that community residents formulate research questions, play a key role in collecting and analyzing data, and are central in helping to translate research outcomes into health improvements. As I edit the preface, a piece that four of us have been collaboratively writing, I make a mental note that we still have to find a nice cover photo representative of the environmental justice issues addressed in this monograph.

12:00. Time to join a national conference call of the Coming Clean Campaign, a coalition of activists from around the country working to challenge the chemical industry to clean up its act. We got involved with the campaign through our work educating the community about the hazardous effects of pesticides and about less toxic alternatives. Working with broader coalitions such as this is invaluable because it enables us to have a more significant impact on national policy. ‘ It’s also one of those activities that, at least for me, easily falls through the cracks in the rush to deal with all our local issues, so I’m excited to be taking part in the conference call today. … I’ll tell you all about it tomorrow.

Wednesday, 3 Oct 2001

NEW YORK, N.Y.

No profound thoughts this morning, just pleased that it’s warm outside, a welcome respite from the unexpected shock of cold that greeted New Yorkers earlier in the week. It may be October, but I’m still not ready to let go of the summer.

Yesterday, I finished up my day by doing something completely different from my normal work routine — attending class. I sat in on an evening lecture of an environmental health sciences course taught by a team of professors at Columbia School of Public Health’s Environmental Health Department. I attended the lecture to begin preparing for another round of WE ACT’s Environmental Health Leadership Training, which I’ll start working on this fall. This training, which WE ACT first conducted in 1998-99, is designed to teach community leaders basic environmental health and science. In the first two versions of the program, we covered topics including lead poisoning, water quality, ambient and indoor air quality, garbage and sanitation, and asthma. Fifty community activists from New York City completed those trainings, learning about sources and transportation of pollution, exposure routes, and health effects. They also learned basic monitoring methods and sources of data and, finally, how to incorporate scientific resources and information into their ongoing organizing and advocacy efforts.

1999 graduates of WE ACT’s Environmental Health Leadership Training.

Photo: WE ACT.

I’m responsible for this year’s Environmental Health Leadership Training, which will differ from the first two ro

unds in a few significant ways. First, the class will be open to environmental justice activists from all over the northeastern United States, and will be taught using a distance learning format. Second, in order to make sure the information we teach activists is in line with what environmental health professionals learn, the training will be based much more closely on the Columbia course I attended last night. We’re also adding three more sessions to the training so we can continue to address specific environmental health issues that we’ve identified as being of particular concern to potential participants.

As I sit in the large lecture hall, I feel like I’m simultaneously on both sides of the podium. I myself have addressed similar audiences on environmental health and justice issues, but part of me flashes back to two years ago, when I was a student listening to a similar lecture at the university where I got my environmental health degree. Now, though, the lecture is being filtered through a completely different lens than that of two years ago, or that of the other students in the room with me. As the professor introduces concepts like “dose-response” and “latency period” in explaining carcinogenesis, the activist in me continually asks herself “How does this apply to our community?” and “How could I understand this concept if I was your average community leader?” I take notes, not on the content of the lecture but on the efficacy of various presentation techniques. Sophisticated graphs are excellent visuals for graduate students who know how to read and interpret them, but they’d probably have to be a lot simpler for my audience. What would be the best way to present statistics? (The complex charts on the screen in front of the classroom just aren’t doing it for me.) On the rare occasion when my mind stops demanding answers to all these questions, I smile at how nice it is to just sit and passively learn something for two hours. I can hardly remember the last time I sat still and kept my mouth shut for this long.

After class I walk slowly home through Washington Heights, past the Audubon Ballroom where Malcolm X was assassinated (now home to a biotech facility), past bodegas and flower shops, past children on bicycles, past Boricua College and the majestic cathedral of Intercession Church, past entrepreneurs who’ve spread their wares — clothing and books, jewelry and toys — on blankets on the sidewalk and are calling out to me in Spanish, “Mira, no vas a encontrar un precio mas mejor.” I decline their challenge to bargain-hunt and keep walking.

The view from the apartment of one of the residents we’re working with.

Photo: Swati Prakash.

When I get home I read through one of my favorite manuals: “Organizing for Social Change,” published by the Midwest Academy. This evening I’m attending a meeting of the tenants association in East Harlem; this is the group I mentioned yesterday that is organizing to get a Department of Sanitation garbage truck depot out of their backyard. Lest you think this is just another “Not In My Backyard” attempt to displace an unwanted land use to “anywhere but here,” take a look at what I mean by “backyard.” There are 20 garbage trucks lined up 15 feet from people’s apartments, and another 10 lined up on the street, in front of a hospital and across the street from a junior high school (which, ironically, also houses the High School for Environmental Studies). When the trucks start up at 4 a.m., nearby residents are treated to an extra early wake-up call of revving engines and clouds of toxic diesel fumes. When the trucks return in the evenings they are often not completely emptied of trash, creating a haven for rats and other pests. The residents have repeatedly asked for help from the Department of Sanitation, and questioned the legality of placing garbage trucks so close to residences. After two years of getting the runaround from the officials in charge, the people who live here are ready to step up their efforts through more concerted organizing and, if necessary, legal action.

This is the heart of environmental racism: the placement of noxious facilities in low-income communities and communities of color. One can speculate as to how such facilities end up in these communities — whether it’s subconscious racism on the part of planners and facility owners, whether it’s the explicit desire to site such facilities in areas where residents are least likely to protest, or whether it’s some complex combination of economic factors like land value. Whatever the causes may be, the way I feel about it is that there’s no way you’d ever see garbage trucks this close to an apartment building in a middle-class white neighborhood. East Harlem is one of the last communities that needs diesel facilities. It has one of the highest rates of childhood asthma in the country, with a childhood asthma hospitalization rate of 28.8 per 1,000 children in 1997, compared to a nationwide average of 3.7 per 1,000. I’ve been amassing scientific literature on the association between exposure to diesel exhaust and asthma exacerbation, and there is no doubt in my mind that diesel exhaust is a terrible thing for people with asthma, especially children.

Thursday, 4 Oct 2001

NEW YORK, N.Y.

This morning I feel like I’ve inadvertently stumbled into some bizarre Three Stooges episode. The refrain echoing in my mind all morning is more coffee, but when I get to work and open the fridge to drop off my lunch, I’m greeted with a pool of water at the bottom. Somehow, the fridge mysteriously decided to defrost itself overnight. After I clean it out with help from a co-worker, I realize there’s no water left in the cooler to make coffee. By the time I replace the empty bottle with a new one from our other office down the hall, I forgot why I needed the water in the first place. It’s 10:30 before I finally get my coffee and get settled in. Maybe this is a sign that I should try to take it easy today.

Along with getting a cup of coffee, my other challenge for this morning is figuring out my travel schedule for next month. I need to be in Los Angeles during the second week of November to help teach an air pollution curriculum developed jointly by WE ACT and the University of Southern California (I referred to this on Tuesday). But I also need to be in Detroit for three days right in the middle of that week for a U.S. EPA Air Toxics workshop. I get on the phone with a colleague at USC and we finally work out a plan that will enable me to get to L.A. by Friday of that week. We decide to spend that day on a class field trip in which the students take a “toxic tour” of point and mobile sources of air pollution in the community and conduct air monitoring with hand-held monitors. I offer to teach my portion of the curriculum during that field trip. By then our own youth program, the Earth Crew, will have completed some of the same curriculum, so I can share our experiences with the youth group in Los Angeles.

Newspaper photo of Earth Crew participants conducting a traffic count in 1997.

Our two communities, Harlem and East L.A., have partnered on this grant because both areas are heavily burdened with diesel exhaust, other sources of particulate air pollution, and traffic noise. Our youth group has also conducted related air monitoring projects in the past, including one in which they measured fine particulate and black carbon concentrations at four intersections in Harlem and compared the results to concurrent traffic c

ounts. The results of this study were written up in both Environmental Health Perspectives and The Uptown Eye, a community newspaper published by WE ACT.

This trip to Los Angeles will also include an opportunity to talk to a national gathering of female state legislators about promoting safe environments for children. Although I feel a little intimidated at the prospect of addressing such a group, I know it’s a great opportunity to encourage legislators from all over the country to pursue state-level policy initiatives that improve children’s environmental health and seek to eradicate the special environmental risks faced by low-income children and children of color. It’s also a good opportunity for me to get out of the niches I feel most comfortable in — air pollution and environmental health sciences, and community organizing — and become more active in WE ACT’s other major mission, to promote environmental justice through political advocacy.

The Uptown Eye, WE ACT’s community newspaper.

Last night’s meeting with the tenants association was great. We finalized the details for the community forum we’re planning for later this month, which will address environmental health concerns related to the garbage truck depot behind residents’ apartments. At the last meeting, we’d decided to start a postcard campaign — blitzing a specific official with a pre-printed postcard demanding that the truck depot be closed down — and last night we decided to have residents who attend the community forum sign the postcards on the spot. We look through some photos of the depot and pick one to make into the postcard. Then I write as the group brainstorms what they want to say in the postcard. We debate potential slogans to print on the front of the postcard, discarding “Your trucks got us all choked up,” and “What if this was your backyard,” and finally settling on “Your trucks are destroying our children’s health.”

We then discuss when would be the best time for me to do a training on community organizing for the association. Actually, I feel a little awkward when I hear myself saying, “I can give a quick training on community organizing.” Throughout these meetings, it’s been challenging to figure out the best role for me to play. How does WE ACT strike the balance between helping this tenants association solve one particular problem, and helping build the association’s own capacity to solve local problems? I envision taking the group through a training that will enable them to develop a comprehensive organizing strategy — identifying goals, potential allies, and obstacles, and then developing several tactics and tools to accomplish their objectives. The law is one potential tool, science is another, and media is a third important tactic. And if all else fails, direct action may become the last option.

Yesterday afternoon WE ACT held a staff meeting to discuss another community forum we are organizing later this month, this one about concerns in Harlem over the World Trade Center tragedy. We identified potential speakers to address four topics: emergency responses and resources for families of victims; dealing with psychological trauma; environmental health issues; and long-term political and economic implications. For a while we get bogged down in a discussion of whether to include a speaker to address backlash against Muslims and people of Arab descent. Finally we decide to accept the fact that this forum can’t address every issue that’s come up since the disaster. Instead, we agree to provide written materials and invite relevant experts to attend and answer questions if they arise. But we decide we probably will need to find a speaker to address the threat of bio-terrorism, particularly with respect to the water supply and ambient air. Suddenly this is starting to feel like a heavy-duty undertaking.

Besides the content of the forum, there are so many logistics we need to cover in order to pull off this event: providing food, securing child care on the premises, and setting up a simultaneous English-to-Spanish translation system, to name a few. I can feel the worry gathering in my shoulders; those are a lot of difficult details to pull off in a short time, on no real budget, while we’ve got plenty of other projects going on. Furthermore, as an organization we’ve struggled over how and whether to organize this forum. Our mission, after all, is to promote environmental health and justice. Although the forum will address environmental health concerns, particularly for people who work downtown, its theme is much broader. But it feels awkward to address other environmental issues in this climate, when so many people’s minds are on the attacks and their aftermath. It’s true that we have an environmental focus, but we are also a community-based organization and feel obliged to respond to community needs arising from the recent crisis. And we all agree that it will be good to contribute to restoring some comfort and security to our still-shaken community.

Friday, 5 Oct 2001

NEW YORK, N.Y.

I’m not exactly sure where this week went. Today I hope to tie up as many loose ends as I can. First I have to finish writing and editing the preface to the supplementary issue of Environmental Health Perspectives. All four authors met on Wednesday to go through our draft again; now I’m going to incorporate our edits and add a few sentences, and send it around one last time for feedback. Hopefully we’ll be able to get this off to the EHP editors by next week and I can put this project on the back burner until April, when the issue will be published. Then we’ll work to disseminate it to a broad audience of environmental justice activists, so it reaches a much wider audience than the environmental health scientists who generally read this journal.

I’m almost through with our edits when the phone rings. “Swati, do you know what the active ingredients of roach gels and traps are?” asks a scientist from another research center we work with, the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health. The Columbia Center is looking at the health effects of various environmental exposures on babies and children, and WE ACT is their community partner. Part of the research they’re doing includes an educational intervention called “Healthy Home, Healthy Child,” in which we educate mothers on ways to reduce their children’s exposures to home environmental hazards, including pests and pesticides. I put my caller on speaker phone while I consult the collection of pesticides I’ve picked up from the 99 cent stores in my neighborhood. WE ACT uses these pesticides as props when we do community outreach to encourage the use of integrated pest management. Many 99 cent stores in low-income communities sell the most toxic pesticides available on the market. Fortunately I haven’t recently come across any containing Dursban (which was pulled from the market last year but took a while to disappear from the street vendors and 99 cent stores up here), but there are still plenty that contain diazinon and chlorpyrifos. I sort through my collection — Black Jack Ratonicide, Raid Ant spray, boric acid (the less toxic alternative we encourage) — but don’t find any roach gels or traps. We find some outdated information on the web and finally Robin decides to conduct some field research by cruising her local 99 cent store and picking up whatever is on the shelves today.

After I get off the phone, I leave a message for the concerned mother who called Monday asking about environmental hazards stemming from the World Trade Center disaster. Unfortunately, I don’t have a lot of good news for her. While it was somewhat helpful to consult with various scientists, many of them gave me predictably scientific answers: “I’d want to look at the sampling methodology myself to see if the technique

s used were the most accurate,” etc. One person tells me he’s heard that the asbestos used in the Twin Towers was made of chrysotile, which is the least toxic of the various forms of asbestos. As near as I can tell, some isolated samples (particularly those taken shortly after the disaster) show a few individual pollutants to be at elevated levels. But for the most part, what the public is being told is that there is no longer reason to be concerned about environmental health hazards outside of the cordoned-off vicinity of the WTC site. I don’t know if this somewhat-confusing information will be encouraging to the mother or not. For every parent and resident who is concerned about health risks and air quality, there are an equal number of individuals who are desperate to return to “life as normal,” and would rather not let environmental health concerns be a stumbling block on that path.

The repercussions from the World Trade Center disaster are rippling through the environmental movement in this city, and possibly all over the country. (It’s hard to have that perspective from here). Politicians at all levels of the government, from our mayor to our president, are urging everybody to try to “resume life as normal,” implying that this is the patriotic thing to do. In some convoluted way this seems to be pitting health and environmental concerns against patriotism and loyalty to our country. I’m very worried about potential long-term health risks being sacrificed in the response to this acute crisis; worried about censorship and intimidation of concerned residents and activists; worried even about writing these thoughts down. Every government body that is conducting monitoring downtown has a vested interest in not causing panic, in promoting a sense of safety and security. Let’s face it, the idealized objectivity of science was lost during the terrorist attacks. Environmental health concerns no longer exist in the same context that they did the day before the attacks. Now the backdrop to our work is “the threat of terrorism,” or “giving in to terrorism,” and the looming cost of attempting to avoid exposure is semi-permanent displacement, a concept no New Yorker can really accept.

Here’s a concrete example of my general concerns about the environmental costs of the World Trade Center disaster: although it’s true that most of the individual contaminants that are being monitored are below levels of concern, what about the effects of breathing in all of these contaminants together? Cumulatively these exposures could have adverse health effects. Because our approach to environmental risk assessment has never adequately addressed the issue of cumulative exposure, right now there’s no good way to evaluate the true risk to New Yorkers.

Children play near a chemical plant in Norco, La.

Photo: Environmental Justice Fund.

My intense reverie is broken by a phone call from a friend asking if I’ll make it down to the 10 year anniversary of the People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, taking place in Washington, D.C., later this month. This historic summit, which was held in Washington in 1991, was the first national gathering of environmental activists of color from around the country. It was during this conference that the landmark Principles of Environmental Justice were formulated. These are the principles that guide my work as an environmental justice activist. This year’s anniversary event will include a one-day press conference and a smaller gathering in D.C.; the Second National People of Color Environmental Summit will take place next year. It was a little too early in my environmental justice career to attend that first summit in 1991, so I can’t wait until next year’s event to connect with environmental justice activists from around the country (like those working in neighborhoods in Norco, La., where residents live 20 feet from the border of chemical refineries). Making these connections will be an invaluable way for me to emotionally and intellectually “recharge,” and continue to live the passion of organizing to improve environmental health in low-income communities of color.