The opening game of the 2022 FIFA World Cup is just days away, and all eyes are on host country Qatar, which has been getting ready to host the international soccer tournament since 2010. The preparations for the event, which organizers pledged would be “carbon-neutral,” have stirred up a significant amount of criticism related to worker exploitation and alleged human rights violations. Now, a climate watchdog group says the tournament’s organizers, which include representatives from FIFA and the Qatar government, misled the public by undercounting carbon emissions in one key area: stadiums.

Qatar has been on a decade-long World Cup construction boom, building seven new stadiums, 30 practice facilities, thousands of hotel rooms, and an expansion to the Doha International Airport.

Back when Qatar was awarded hosting privileges for the tournament, the event’s organizers pledged to offset all unavoidable emissions, largely through carbon credits. But achieving this “carbon-neutral” goal depends on a comprehensive accounting of all emissions associated with the World Cup, something researchers at the group Carbon Market Watch say FIFA and Qatar have failed to do.

“The main issue we found was with the construction of the stadiums,” said Gilles Dufrasne, policy officer for Carbon Market Watch and the author of the report, which was updated last month. He raised concerns about the placement of the stadiums and how they might be used in the future – two factors he says organizers did not sufficiently take into account in their carbon footprint calculations for this year’s tournament.

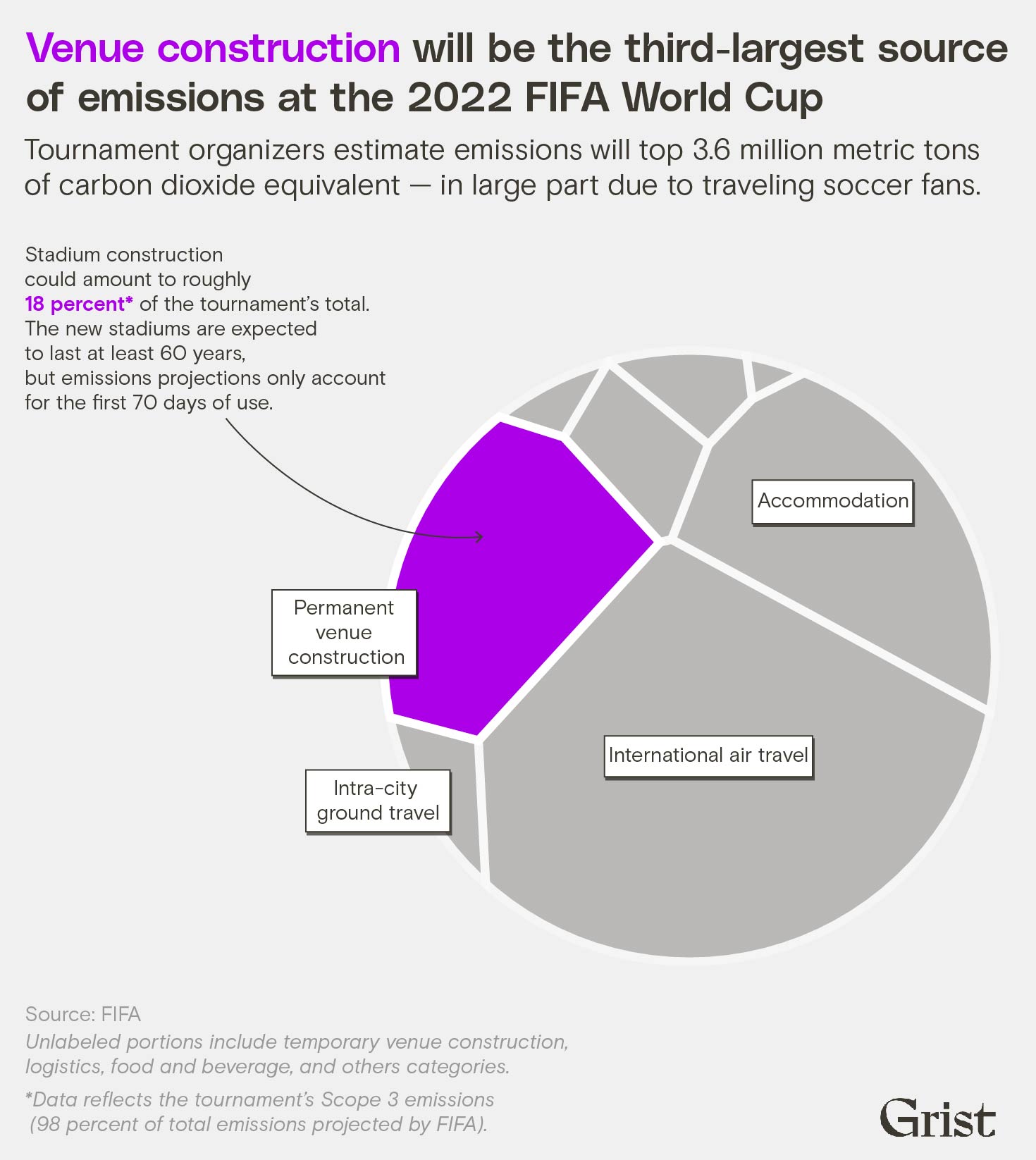

Already one of the hottest countries on Earth, Qatar faces worsening heat waves and water shortages as climate change intensifies. FIFA predicts activities related to this year’s World Cup will amount to 3.6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, the equivalent of nearly 460,000 homes’ energy use for a year. According to FIFA’s latest emissions report, the largest sources of tournament-related emissions come down to air travel and accommodations, as more than 1.2 million fans are expected to attend the event from all over the world.

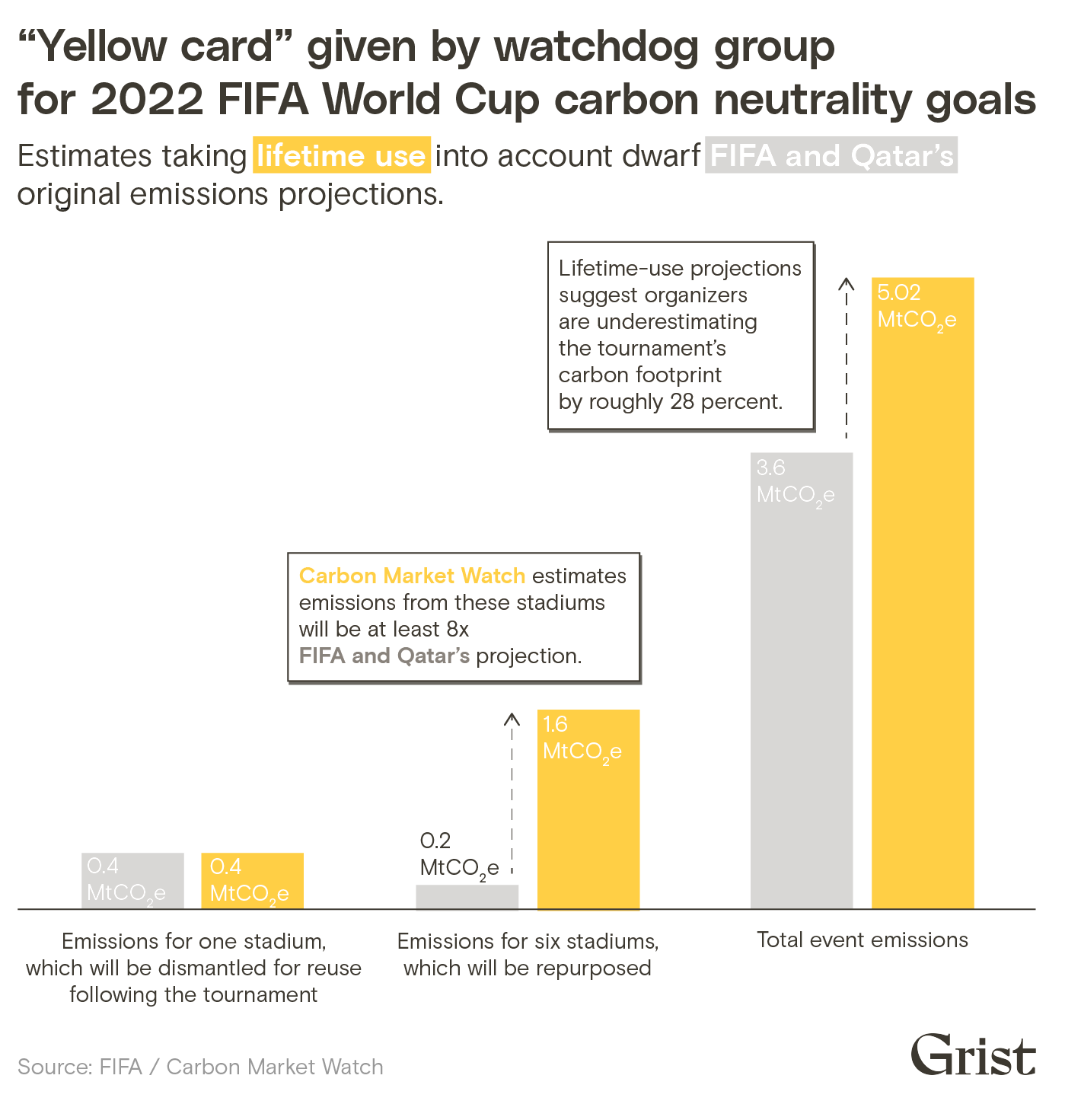

Stadium construction, meanwhile, accounts for roughly 18 percent of the group’s carbon estimations. In its report, tournament organizers calculated stadium emissions by splitting them between two different categories: temporary and permanent seats. Of the seven new stadiums built for the Qatar tournament, World Cup organizers plan to dismantle one entirely and reduce the capacity of the others by nearly half.

For temporary seats, organizers hold themselves accountable for just 70 days’ worth of emissions — the length of the upcoming tournament combined with two lead-up FIFA World Cup Club events. But Carbon Market Watch noted that methodology didn’t track with previous FIFA reports, which stated the lifetime of a stadium can be up to 60 years. The climate watchdog group used FIFA’s previous reports to estimate a new emissions total for 2022 World Cup stadiums.

Under these new guidelines, researchers found the total footprint for the six permanent stadiums will amount to at least eight times organizers’ original carbon accounting.

Then there’s the issue of location: Each of the eight stadiums used for the World Cup are within roughly 30 miles of Doha’s city center. While the high concentration of stadiums will reduce emissions associated with fans traveling between venues, the facilities could create long-term problems for the city’s 2.4 million residents.

Figuring out what to do with leftover stadiums is a well-known problem for cities that have hosted huge athletic events, such as the World Cup or the Olympics. Known as “white elephants,” these expensive, world-class venues can fall into disrepair, taking up valuable space while draining local resources.

World Cup organizers in Qatar have tried to get ahead of this issue by making plans to turn what remains of these stadiums into community hubs, hotels and education centers. But in its report, Carbon Market Watch casts doubt on the practicality of this plan.

For example, the new, 40,000-seat Al Janoub stadium is slated to become home to a local soccer team. After the World Cup, the stadium’s capacity will go down to 20,000, but that’s still a big bump up for the club, which currently plays in a stadium with 60 percent that capacity.

“It is unclear whether the local team will attract a sufficient crowd to fill, and maintain, the new stadium, and what will happen to the 12,000 seat stadium they previously used,” Carbon Market Watch reported. “Overall, it is very difficult to assess the credibility of the legacy plans. These depend strongly on demand from the local population, as well as interest from companies to invest in maintaining the infrastructure.”

As for Qatar’s temporary Stadium 974, named after the country’s international dialing code, FIFA has not yet announced any concrete plans for how or if the materials might be reused. The stadium was built from shipping containers so that it could theoretically be dismantled and reconstructed elsewhere. Carbon Market Watch noted that FIFA has not announced plans on where the stadium might find a new home, nor plans for the upper-tier seats that will be removed from the permanent stadiums. The emissions accrued during the transportation and reconstruction of these materials are not accounted for in FIFA and Qatar’s carbon calculations.

“It’s an interesting concept,” said Dufrasne on the idea of repurposing a stadium. But there’s a catch: “If you have the temporary stadium, and you transport it quite far away, and you reuse it only once,” he said, “then actually it’s potentially worse than having two permanent stadiums in those two different locations.”

According to its sustainability report, FIFA and Qatar plan to offset unavoidable emissions with carbon credits and through other measures such as planting trees. But Carbon Market Watch argues the groups should not market this year’s World Cup as carbon-neutral until organizers do a more comprehensive accounting of the event’s long-term footprint. Carbon Market Watch called on FIFA to take on a new carbon calculation that includes direct and indirect emissions.

“It’s highly misleading to make carbon neutrality claims today,” Dufrasne said, “ and there are very, very few, if any, companies that do it correctly.”

FIFA did not comment on the findings of the Carbon Market Watch report, but it is expected to release an updated emissions report following the conclusion of the tournament.