In the postmodern United States, a cultural critic laments, “The pleasures of the table are rarely appreciated at face value.”

Speak truth to flour.

A near-hysterical concern with health has replaced common sense, he continues, leading to all manner of dubious decisions: “Americans blithely drink sodas filled with artificial flavors and sweeteners, yet paste warning labels on bottles of wine; they decry the dangers of eating butter and claim that margarine, a completely manufactured artificial product, is better for you.”

For Americans, he worries, eating has been drained of joy and imbued instead with anxiety. “Are we so out of touch with our senses, our intuition, and our cultural heritage,” he wonders, “that we cannot eat without consulting medical journals and diet books?”

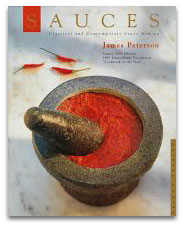

This mini-jeremiad on the vexations of the American table would not be out of place in the latest Michael Pollan essay. Yet I encountered it nearly 15 years ago, in James Peterson’s landmark Sauces: Classical and Contemporary Sauce Making.

I got to thinking about Peterson’s wonderful cookbook a couple of weeks ago, while immersed in my three-column farm bill series. My research reminded me that for most of the last 100 years, food production in the United States has undergone a steady process of mystification. More and more, Americans are content to let others not only grow their food for them, but also cook it.

A Dash of Spice

There are several ways to illustrate our alienation from food production. Here’s one: In 1905, the USDA tells us, households spent nearly 90 percent of their total food budgets on food to be consumed within the home. One hundred years later, Americans spend almost half of their food budgets eating out, and much of what they eat within the home is heat-and-serve fare that requires no real cooking.

Now, when writing about these trends, it’s too easy to lapse into a sort of nostalgia that’s really no different from historical amnesia. History offers few lost paradises. People may have been cooking and eating lots of fresh food in 1905, but social relations around food production weren’t rosy. Still 15 years from gaining the right to vote, women bore the brunt of all that household industriousness. Few Americans today could easily withstand the rigors of keeping a house without electricity, modern appliances, and a nearby supermarket. Nor will many African-Americans look back fondly on the era. The promises of Reconstruction had decisively collapsed, and white-supremacist ideology reigned in the north and south alike.

Even so, it’s worth cataloging what’s been lost as food production industrialized over the course of the century. A country marked by sturdy regional cuisines, enriched by waves of immigration from throughout the globe, mutated into Fast Food Nation. Homogenization, portability, and convenience became the hallmarks of U.S. eating. Flavor became less the concern of the farmer and cook and more the realm of the corporate food scientist. Untethered from the dirty work of production, U.S. consumers became “free to choose” from a vast array of items at supermarkets and fast-food chains — most of which, it turns out, amounted to clever combinations of corn and soybeans, our two most prodigious, subsidized, and thus inexpensive crops.

Yet things are never as clear-cut as they seem. In the post-World War II decades, just as these trends gained force, a backlash began to take root. It started when young Americans like Julia Child and Richard Olney traveled to southern Europe and tasted farm-fresh food prepared with flavor and tradition — not volume and profit — as the primary motivating factors.

These writers didn’t plan to launch a revolution. They fell in love with vibrant flavor and fell upon cookbook writing as a means for building a career around food. Their audience certainly wasn’t 1905-style rural homesteaders feeding a family from backyard produce. Rather, the target was a burgeoning middle class — buoyed by the postwar boom — that could be convinced to see cooking as a leisure activity.

Thus a new genre was born. Previous American cookbooks had been geared to harried housewives scraping together family meals from common ingredients. Child and Olney ushered in an age of almost scholarly texts, where American writers venture off to foreign lands and record their culinary customs with the zeal of anthropologists. We remain in the midst of the cookbook renaissance they launched.

A New Crop of Cooks

By the early 1970s, the post-war boom had gone bust and 20 years of solid growth in real wages had ground to a halt. But the idea of elaborate weekend cooking lived on. In my own early-1970s childhood in Austin, Texas, my (working) mother plied us with Hamburger Helper and TV dinners during the week. But on the weekends, she would occasionally expand her reach in the kitchen for lavish dinner parties — often using Child’s epoch-making Mastering the Art of French Cooking, which she had gotten as a wedding gift 15 years before, as a guide.

I was a terrible eater as a child. I considered McDonald’s burger, adorned with French fries shoved under the top bun (I despised pickles; lettuce was taboo), the height of culinary excellence. I didn’t have much interest in many of my mother’s weekend kitchen triumphs. But I remember being stopped in my tracks by the genius of my mom’s Julia Child éclairs — made from a pastry dough called pate a choux that puffs up when baked to create a hollow, to be filled with custard. The tops of the little masterpieces are then topped with melted dark chocolate. Wolfing down a McDonald’s burger or three was fun but fleeting; getting my hands on one of those éclairs, though — that was an experience, a message, not to be heeded until years later, that food offered subtle satisfactions.

All over the nation, even as our culinary culture continued its descent into the dead-end alleys of industrialization and fetishized convenience, similar epiphanies were afoot all over the country. Writers like Paula Wolfert, Diana Kennedy, Jeffrey Alford, and Naomi Duguid continued down the trail blazed by Child and Olney. Something remarkable had happened. A nation that had all but eviscerated its own regional cuisines and outsourced its cooking to Kraft and McDonald’s had nevertheless given birth to a vibrant and revolutionary food literature. I say revolutionary because their work has awakened people all over the country in unpredictable ways to the power of vivid flavor.

As I mentioned above, the goal was never to overthrow industrial food, much less to challenge the brutal class politics that govern food production. Rather, it was nothing more or less noble than to sell books to a prosperous middle class. But the pure passion for food with which those books were written gave them force well beyond those modest intentions.

Today, even as corporate giants such as Monsanto and Archer Daniels Midland consolidate their grip over how most food is grown and consumed in this country, people are forging new relationships with and around food. They’re flocking to farmers’ markets, joining CSAs, growing food in urban community gardens. And apolitical food writers like Julia Child occupy an unexpected but undeniable place in that movement.

To this day, they help us reimagine our relationship to what we eat and give us access to strong regional traditions the world over. When I get lost in the details of planning the upcoming farm season or poring over arcane points in the 2007 farm bill debate, they remind me that so much of what I’m doing is all about the food.