Coastal residents of poor and fast-growing tropical countries face rapid increases in the numbers of once-rare floods they may face as seas rise, with a new statistical analysis offering troubling projections for regions where sea-level data is sparse.

Stark increases in instances of flooding are projected for Pacific islands, parts of Southeast Asia, and coastlines along India, Africa, and South America in the years and decades ahead — before spreading to engulf nearly the entire tropical region, according to a study led by Sean Vitousek, a researcher at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Residents of Kerala in southern India face sharp increases in the number of floods in the years ahead. Thejas Panarkandy

“Imagine what it might feel like to live on a low-lying island nation in the Pacific, where not only your home, but your entire nation might be drowned,” Vitousek said.

The researchers combined a statistical technique used to analyze extreme events with models simulating waves, storms, tides, and the sea level effects of global warming. They created snapshots of the future — flood projections that can be difficult to generate with the limited ocean data available in some places.

“If it’s easy to flood with smaller water levels coming from the ocean side, then gradual sea-level rise can have a big impact,” Vitousek said. “For places like the Pacific islands in the middle of nowhere that don’t have any data, we can make an assessment for what’s going to happen.”

The study found that the frequency of formerly once-in-50-year floods could double in some tropical places in the decades ahead. The findings were published Thursday in the Nature journal Scientific Reports.

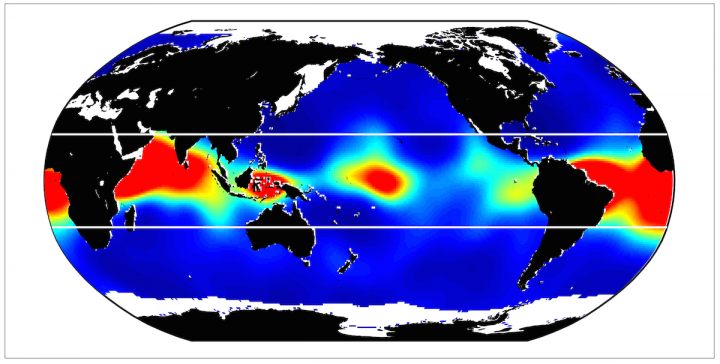

Red areas in this map represent large projected increases in the frequency of floods following 10 centimeters (four inches) of additional sea-level rise. Vitousek et al.

“This is the first paper I’ve seen that tries to combine all these different elements in the context of sea-level rise,” said Richard Smith, a statistics professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who studies environmental change. “They’ve done it in a very systematic and well organized way.”

The tropics are home to some of the world’s most vulnerable coastal residents, often living in houses made from flimsy construction materials, under governments that have limited ability to provide food, water, and care when disasters strike.

“Many poor developing countries like Bangladesh are going to see greater frequency and magnitude of flood events — even with the best efforts to reduce emissions,” said Saleemul Huq, director of the International Center for Climate Change and Development in Bangladesh.

Residents of these sweltering regions have released little of the greenhouse gas pollution that’s warming the Earth’s surface, melting ice and expanding ocean water, and causing seas to rise. Global temperatures have risen nearly 2 degrees F since the 1800s.

“These vulnerable countries and communities need to be supported to improve early warning and safe shelters — followed by economic support to recover afterwards,” Huq said.

All coastal regions face risks from rising seas, though the nature of the hazards varies. Seas are rising at about an inch per decade globally, at an accelerating rate with several feet or more of sea rise likely this century. Detailed information on water levels in many vulnerable places, however, is sparse.

“Understanding of sea-level rise in the tropics is challenging because there’s a lack of long-term data,” said Benjamin Horton, a Rutgers professor who wasn’t involved with the study. “Tide gauges were installed for navigation in ports; big trade was between the industrialized nations of Europe and [the] U.S.”

Unlike vulnerable cities and towns along the East Coast of the U.S., where frequent storms and big waves lead to large variations in day-to-day water levels, tropical coastlines tend to be surrounded by waters with depths that vary less. That means many tropical coastlines were not built to withstand the kinds of routine flooding that will be caused by rising seas.