For decades, the residents of San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood have sounded the alarm that industry emissions and pollution in their backyard are making them sick.

Located right off the Bay in the southeastern corner of the city, the historically black neighborhood has played host to a number of pollution sources over the years. It is home to a sewage treatment facility and surrounded by freeways that carry vehicle fumes over residences. A former Navy nuclear research facility is now a Superfund site dogged by a sloppy cleanup that workers involved in the project say was faked.

“Bayview-Hunters Point is a picture postcard of environmental racism and injustice,” says Bradley Angel, executive director of Greenaction, a grassroots health and environmental group based in San Francisco.

Studies had found higher rates of some cancers in Bayview versus the city at large. And asthma has been a serious public health issue: A 2000 report found that one in six kids and one in ten overall residents reported having the respiratory illness.

But with so many polluters in this neighborhood, there has been little accountability, notes Michelle Pierce, a longtime resident and executive director of Bayview Hunters Point Community Advocates. In response to the community’s health complaints, she says local government tended to stick to the same line: “We can’t place blame on any one factor.”

Now it can at least assign some responsibility to a now-closed industrial facility. Two recent studies have assessed the effects on reproductive outcomes caused by a single local polluter: a Pacific Gas & Electric power plant that had operated in the neighborhood from 1929 to 2006. More than a decade since the PG&E plant closed in Bayview-Hunters Point, the new research lends credence to residents’ long-espoused health concerns.

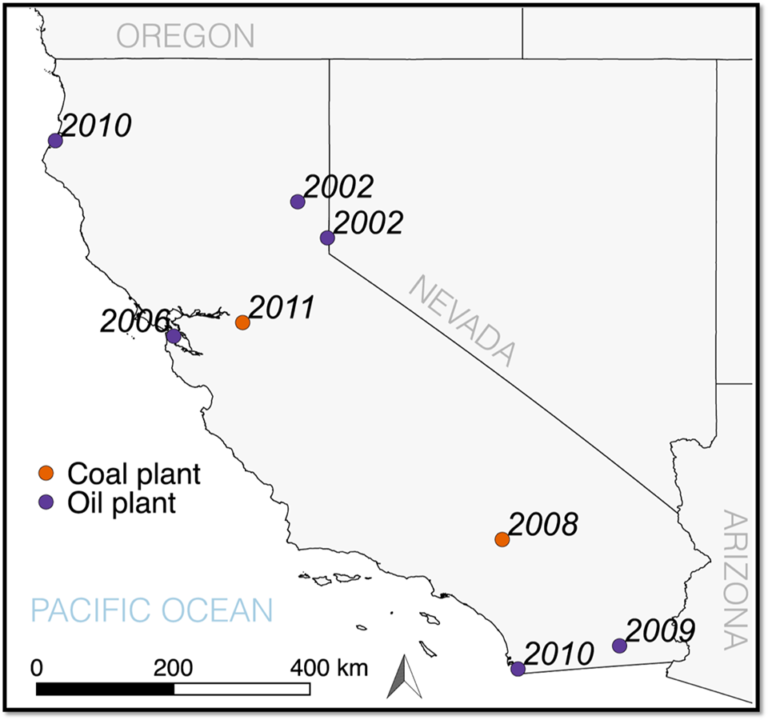

A study published in May in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that after eight coal or oil-fired power plants closed between 2001 and 2011 in California — including the PG&E facility in Bayview-Hunters Point — fewer babies were born preterm in surrounding communities.

Previous research has shown that air pollution may cause reactions in the body, causing pregnant women to give birth early, says Joan Casey, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral scholar at University of California, Berkeley. (Grist board member Rachel Morello-Frosch is also a study coauthor.) Babies born preterm — before 37 weeks of pregnancy — are at an increased risk of death, as well as conditions such as cerebral palsy or asthma.

The eight California coal and oil-fired power plants closed between 2001 and 2011 included in the study. Image courtesy of Joan Casey

The researchers analyzed birth data in areas near all eight power plants before and after each closed. Those numbers were compared with communities further away from the facilities — and presumably less affected by the site — to help isolate the impact of the power plants.

For those living within roughly three miles of the plants, the team concluded that closing the facilities dropped preterm birth rates from seven percent to 5.1 percent, effectively decreasing the number of preemies born by a quarter.

In a separate study published in Environmental Health in May, the same group of researchers found that retiring those eight power plants resulted in another health benefit: an uptick in fertility rates — the number of live births per 1,000 women.

Interestingly, the benefits of a power plant’s closure weren’t distributed equally across race. Black residents, for instance, experienced one of the greatest drops in preterm birth rates — and Casey points to several factors that help explain that finding.

Low-income groups and people of color are more likely to live close to a power plant. Black people, for example, are 75 percent more likely than the average American to live next to an industrial facility. And in the case of the eight sites studied, on average, black women tended to live within roughly a mile of the retired power plants, while white women, for instance, lived more than 2 miles away.

Black women are also at a 50 percent higher risk of delivering their babies early, in general, and thus had more to gain from the plant closure, Casey explains. This startling and mysterious statistic is relatively stable across education level, and some doctors suspect it’s due to higher levels of stress experienced by black women due to the racism they face in the U.S.

“This is a really concrete step that could be taken in terms of potentially reducing health disparities,” Casey says. “Some of this information could be used perhaps in decisions about which power plants to focus on retiring first to improve health equity.”

It was grassroots organizing from groups like Greenaction and Bayview Hunters Point Community Advocates that finally helped close the PG&E plant in 2006 — in what Bradley Angel calls “an incredible example of community persistence.” The new research validates those groups’ work, though the results don’t surprise Michelle Pierce at all.

“We absolutely knew to expect those kinds of health outcomes,” she explains. “It’s not news to anybody with a little bit of technical knowledge or anybody with direct contact with the people out here.”