Tucked away in the most extreme nooks and crannies of the Earth are biodiverse galaxies of microorganisms — some that might help scour the atmosphere of the carbon dioxide mankind has pumped into it.

One microorganism in particular has captured scientists’ attention. UTEX 3222, nicknamed “Chonkus” for the way it guzzles carbon dioxide, is a previously unknown cyanobacterium found in volcanic ocean vents. A recent paper in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology found it boasts exceptional atmosphere-cleaning potential — even among its well-studied peers. If scientists can figure out how to genetically engineer it, this single-celled organism’s natural quirks could become supercharged into a low-waste carbon capture system.

Cyanobacteria like Chonkus, sometimes referred to by the misnomer blue-green algae, are aquatic organisms that, suck up light and carbon dioxide and turn it into food, photosynthesizing like plants. But tucked away inside their single-celled bodies are compartments that allow them to concentrate and gobble up more CO2 than their distant leafy relatives. When found in exotic environments, they can evolve unique characteristics not often found in nature. For microorganism researchers, whose field has long revolved around a handful of easy-to-manage organisms like yeast and E. coli, the untapped biodiversity heralds new possibilities.

“There’s more and more excitement about isolating new organisms,” said Braden Tierney, a microbiologist and one of the lead authors of the paper that identified Chonkus. On an expedition in September 2022, Tierney and researchers from the University of Palermo in Italy dove into the waters surrounding Vulcano, an island off the coast of Sicily where volcanic vents in shallow waters provide an unusual habitat — illuminated by sunlight and yet rich with plumes of carbon-dioxide. The location yielded a veritable soup of microbial life, including Chonkus.

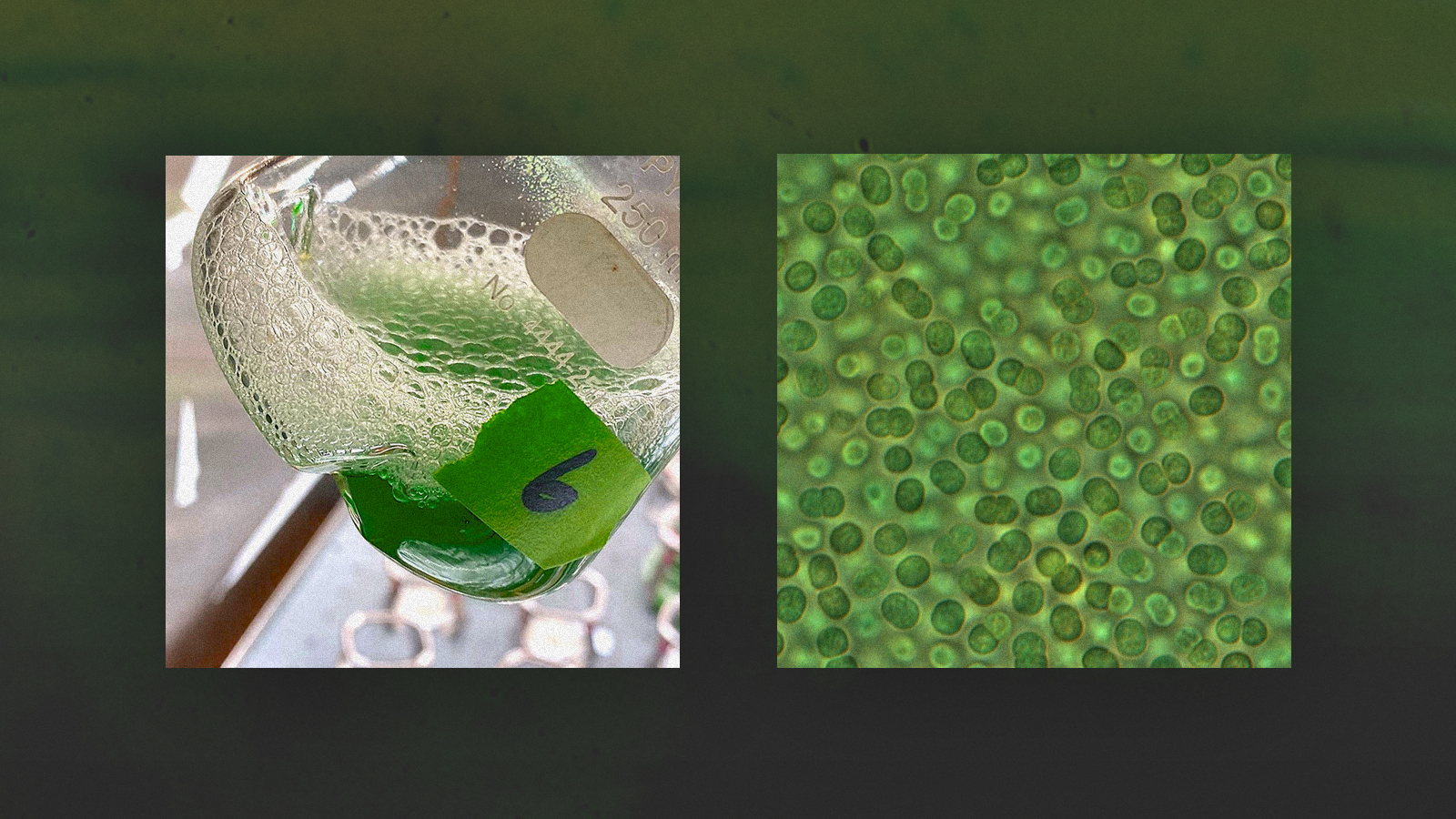

After Tierney retrieved flasks of the seawater, Max Schubert, the other lead author of the cyanobacteria paper and a lead project scientist at the scientific nonprofit Align to Innovate, got to work identifying the different organisms in it. Schubert said that out in the open ocean, cyanobacteria like Chonkus grow slowly and are thinly dispersed. “But if we wanted to use them to pull down carbon dioxide, we would want to grow them a lot faster,” he said, “and grow in concentrations that don’t exist in the open ocean.”

Back in the lab, Chonkus did just that — growing faster and thicker than other previously discovered cyanobacteria candidates for carbon capture systems. “When you grow a culture of bacteria, it looks like broth and the bacteria are very dilute in the culture,” Schubert said, “but we found that Chonkus would settle into this stuff that is much more dense, like a green peanut butter.”

Chonkus’ peanut butter consistency is important for the strain’s potential in green biotechnologies. Typically, biotech industries that use cyanobacteria and algae need to separate them from the water they grow in. Because Chonkus does so naturally with gravity, Schubert says, it could make the process more efficient. But there are plenty of other puzzles to solve before a discovery like Chonkus can be used for carbon capture.

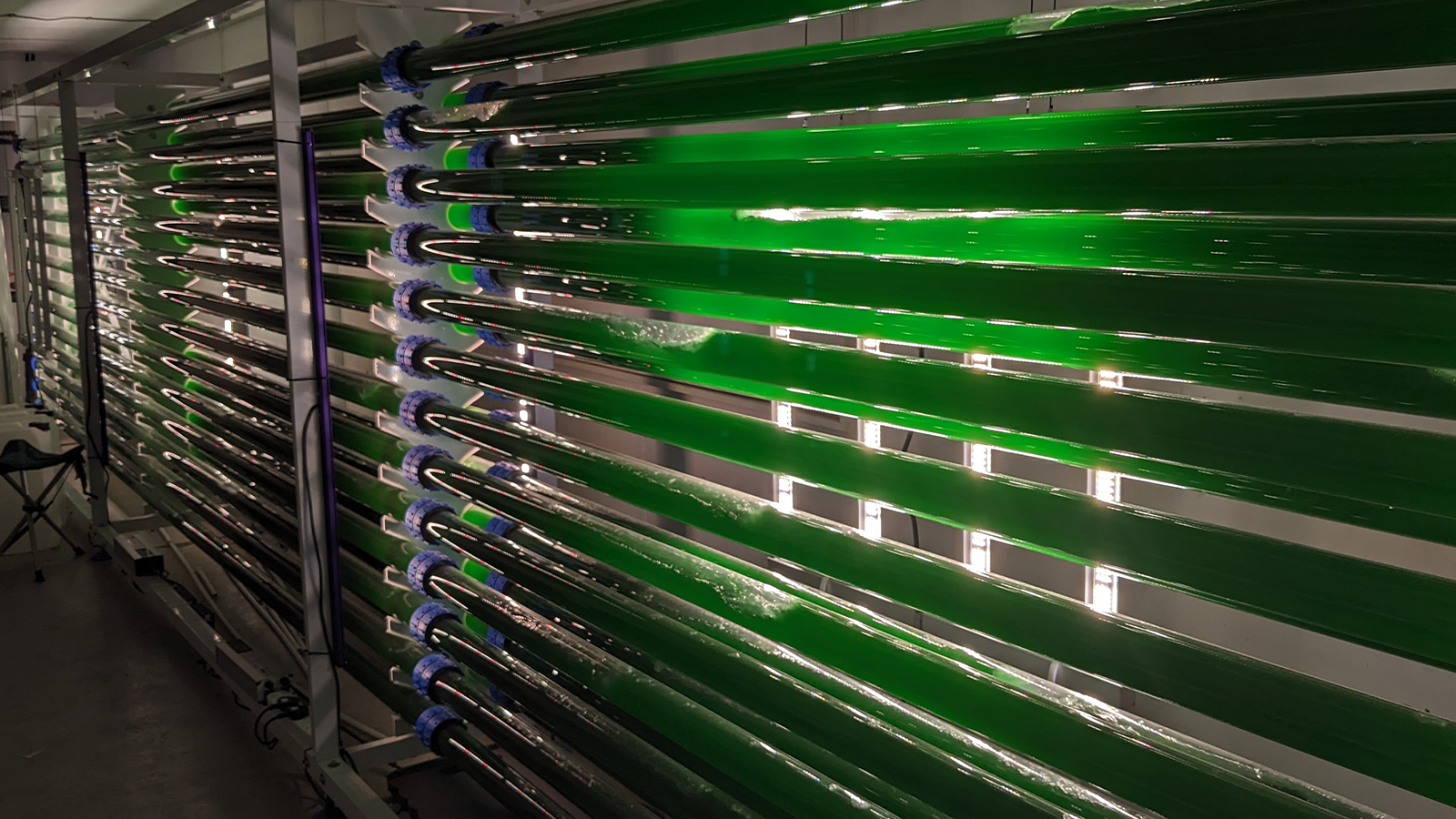

CyanoCapture, a cyanobacteria carbon capture startup based in the United Kingdom, has developed a low-cost method of catching carbon dioxide that runs on biomass, housing algae and cyanobacteria in clear tubes where they can grow and filter CO2. Although Chonkus shows unique promise, David Kim, the company’s CEO and founder, said biotechnology companies need to have more control over its traits, like carbon storage, to use it successfully, and that requires finding a way to crack open its DNA.

CyanoCapture

“Oftentimes we’ll find in nature that a microbe can do something kind of cool, but it doesn’t do it as well as we need to,” said Henry Lee, CEO of Cultivarium, a nonprofit biotech start-up in Watertown, Massachusetts, that specializes in genetically engineering microbes. Cultivarium has been working with CyanoCapture to help them study Chonkus but has yet to figure out how to tinker with its DNA and improve its carbon capturing attributes. “Everybody wants to juice it up and tweak it,” he said.

Since the expedition to Vulcano where Tierney scooped up Chonkus, the nonprofit he founded to explore more extreme environments around the world, the Two Frontiers Project, has also sampled hot springs in Colorado, volcanic chimneys in the Tyrrhenian Sea near Italy, and coral reefs in the Red Sea. Perhaps out there, researchers will find a chunkier Chonkus that can pack away even more carbon, microbes that can help regrow corals, or more organisms that can ease the pains of a rapidly warming world. “There’s no question we’ll keep finding really, really interesting biology in these vents, Tierney said. “I can’t stress enough that this was just the first expedition.”

Kim noted that out of all the microbes out there, less than 0.01 percent have been studied. “They don’t represent the true arsenal of microbes that we could potentially work with to achieve humanity’s goals.”