On a sunny Friday evening in early April, a group of Seattle activists met in a window-lined, trendy events hall to celebrate a change to the city’s zoning code. The room was euphoric. Toddlers crawled on couches; beaming adults embraced and posed for photos. It was also tinged with relief. The passage of a plan that allows denser development in the city had taken four years, countless meetings, and a court battle.

So far, this is the biggest step Seattle has taken towards tackling its housing crisis. Before the plan, 75 percent of the city was set aside for single-family homes, a policy which squeezed new growth into a few neighborhoods and drove up the price of housing citywide. The new plan would allow for denser development on about 6 percent of that exclusionary zoning. That might not seem like much, but for Seattle, where long-time homeowners love their quaint, bungalow-lined streets, it was a big deal. At April’s party, every speech ended on a similar note: “This is just a first step.”

All across the country, activists in liberal cities are pushing for zoning reform to allow for more density. Many American cities are booming — Seattle’s population is up 20 percent since 2010 — and to accommodate that growth, they can either build up or out. Dense, walkable cities mean more families can afford to stay and public transport gets a boost. They’re also better than the alternative: Suburbs, with their large homes and car-dependent multitudes, are a huge driver of carbon emissions. As pro-density leaders in California put it: “Housing policy is climate policy.”

But changing zoning rules isn’t easy. Housing policy might be critical to cities, but it’s also dry and inaccessible, and so the work of these pro-density agitators hasn’t necessarily been changing hearts and minds; it’s been about connecting the dots for those who didn’t see what they had to gain.

The losses are much more visible. Homeowners and neighborhood groups often rise up when cities attempt to update zoning rules. These groups worry that putting more people in a neighborhood will bring more traffic and gentrification and that greedy developers will tear down beautiful old homes for bland, look-alike condos.

It’s easy to see the appeal of that argument. The changes brought by density are immediate: cut-down trees, a lack of parking, and the demolishment of that adorable bungalow down the street. The benefits, on the other hand, play out over years in the ether of the rental market.

But opponents can also veer into NIMBYism (not in my backyard-ism) that can be extreme. That was on display at Seattle’s public comment meetings in late February and early March: “The density Bolsheviks are coming to town,” said one man, “and they’re gonna burn your single-family house to the ground.”

It’s easy to get density opponents fired up — they feel their neighborhoods are threatened, after all. So a big part of the YIMBY (yes in my backyard) movement boils down to building a base that actually cares about zoning.

There’s one YIMBY movement that exemplifies that success — in Minneapolis.

In December, the city council passed Minneapolis 2040, the first zoning reform of its kind anywhere in the country. The plan will eliminate all single-family zoning in the city: Developers will be able to put small, three-unit apartments known as triplexes on any lot. The plan also expands protections for renters, encourages development around public transit, and engages historically marginalized communities in planning decisions.

Minneapolis’ plan has been applauded in liberal enclaves from Vermont to Seattle, and the activists who fought for it are giving talks from Boston to Portland, Oregon. So how did Minneapolis pass such an ambitious plan, when Seattle and other cities are still inching along?

Bringing up YIMBY

The story of Minneapolis 2040 starts in 2013 with the election to the city council of someone looking to implement a denser vision for the city: Lisa Bender, now the council’s president.

Bender has a mantra: “80 percent of my constituents are renters.” That meant she entered office in 2014 with her eye on a group of residents that was more diverse, less wealthy, and younger than those who usually show up to city council meetings on zoning.

She soon got a seat on the city’s zoning planning committee. “I was so excited about the opportunity for a comprehensive plan update in our city,” she said, then paused. “That’s probably an unusual thing to want to work on.”

At first, that meant incremental change. The council loosened restrictions for homeowners to add rentable structures like mother-in-law cottages, then reduced parking space requirements for some new buildings. Those victories, Bender has said, opened up new conversations in the city, and gave residents concrete examples of what it would look like if, say, some multi-family houses were built in single-family neighborhoods.

Around the same time, Neighbors for More Neighbors, a pro-density group that describes itself as only “YIMBY-aligned,” began as the pet art project of John Edwards and Ryan Johnson. Or, as Edwards put it bluntly: “We started out doing these memes.”

The seed of Neighbors for More Neighbors was planted when Edwards went to his first neighborhood meeting. He’d seen NIMBY posters warning about a proposed apartment building, and wanted to know what the problem was. “The meeting was shockingly hostile,” he said. “A crowd of older white people who didn’t want more renters in the neighborhood.”

Edwards was a renter at the time, and began tweeting what he heard at the meetings, partly as catharsis, partly for entertainment. In the amorphous style of internet activism, those tweets morphed into a local-news blog, then a series of pro-density memes produced along with Johnson.

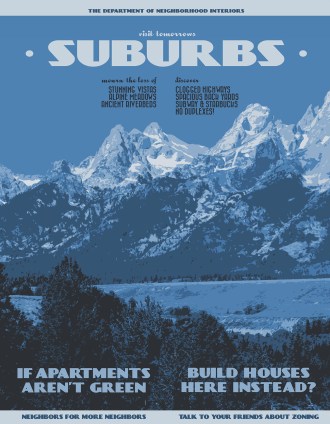

The way Edwards sees it, the NIMBY talking points — concerns over neighborhood character and belligerent renters — are a kind of propaganda, “so it’s time for some counter-propaganda.” The early Neighbors for More Neighbors memes were done in the style of National Parks advertisements. “Remember: Only you can prevent sprawl,” says a beaver in a park ranger hat. “Help keep America green. End single-family zoning.”

The goal was to make denser zoning palatable, Edwards said, because although most people have a stake in zoning reform, it’s the kind of bone-dry policy work that makes eyes glaze over.

By 2017, the posters were being handed out at a new national YIMBY conference, and Edwards and Johnson were sending out action alerts to their followers, trying to build local support for new housing developments. Bender, the city councilmember, directed supporters to Edwards’ blog during one particularly vicious pro-NIMBY attack by a reality TV star.

In the meantime, the city was cranking away on Minneapolis 2040. Under the leadership of Bender and a freshly elected group of progressive city councilmembers, the city had focused on getting feedback for the plan from traditionally overlooked groups, like immigrant communities and historically black neighborhoods.

It wasn’t until last year, when news of the plan was leaked to the Minneapolis Star Tribune, that Neighbors for More Neighbors coalesced into a political organization. Before the plan was public, Edwards said, the pro-density advocates were “just loosely a group of people who believed in the same thing.” Some were environmentalists, others racial justice activists or tenants advocates.

At the time, said Andy Mannix, a reporter with the Minneapolis Star Tribune, “There was momentum on the city council, but there were undecideds as well.” Red signs proliferated across the city, warning of bulldozers gassing up to level homes for big developers, and several councilmembers had expressed opposition to the plan.

Five years ago, that might have been where the ambitious plan faltered. Instead, Neighbors for More Neighbors kicked into high gear.

“We wanted to make the city aware that they had support for a positive long-term vision,” said Anton Schieffer, another group leader who came to YIMBYism by way of social media.

“It’s so easy for housing opponents to say ‘no’ to everything. But saying no is essentially advocating for the status quo” — a status quo with segregated neighborhoods and rising rents, Schieffer said.

The memes might have developed a YIMBY base, but it was the subsequent face-to-face organizing that made a difference, said the group’s leaders. When the plan’s comment period opened, Neighbors for More Neighbors organized supporters to comment on the plan’s website (Heather Worthington, Minneapolis’ director of long-range planning, said the city read every comment, and changed the plan in response).

Neighbors for More Neighbors brought supporters to public hearings and printed signs. “At street festivals over the summer, people would ask, ‘Are you guys the opposite of the red sign people?’” Edwards wrote on his blog, referring to the rapidly proliferating NIMBY signs. “And then they would take home [our] sign.”

They also held neighborhood walks and invited city councilmembers. “Walking around the neighborhood opened up conversation topics that wouldn’t come up otherwise,” Schieffer said. They pointed out how rising property values created an incentive for developers to buy small houses, tear them down, and build McMansions on the empty lot, because the city’s zoning rules didn’t let them build apartments — a factor cited by one city councilmember in his eventual support for the plan.

Neighborhood groups, usually centers of NIMBYism, largely stayed out of the fight. At least one, the Prospect Park Association, even testified in support. Vince Netz, the association’s then-president, said that other board members originally “hated” the plan. But the association took an inventory of existing housing stock — originally with help from Neighbors for More Neighbors — and realized that Prospect Park, ostensibly single family, already had plenty of small apartments and multi-family homes. “Once we started showing people that, they slowed down,” he said. The association’s board voted unanimously to support the 2040 plan.

In the end, the city council passed Minneapolis 2040 on a 12-1 vote, just nine months after it was leaked. The final hearing brought out detractors. But it also had supporters: Elderly people speaking in favor of walkable neighborhoods; young people concerned about climate change; and a union president who argued that sprawling cities were “bad for workers, and bad for families.”

Without the YIMBYs, the Neighbors for More Neighbors organizers think, the eventual plan would have been substantially watered-down, or consensus never would have emerged. As Edwards put it, the YIMBYs had city council “looking over both shoulders.”

Seattle ZONE

That success has awarded Neighbors for More Neighbors a kind of cult status in other cities. Rob Johnson, a former Seattle city councilmember described as the “shepherd” of Seattle’s zoning overhaul, lined the walls of his office with Neighbors for More Neighbors posters. One, with words superimposed on a woodblock print of a glacier-capped mountain, reads: “They said apartments weren’t green, so we put houses here instead.” It’s beautiful, Johnson said.

The zoning update wasn’t the first time in recent history that Seattle had tried to embrace density. “For about two decades, the city had been trying to enact an [affordable] housing program with no success,” said Patience Malaba, outreach director at Seattle for Everyone, the city’s major pro-density coalition. (Seattle’s zoning reforms come with low-income housing requirements, and a similar provision was passed in Minneapolis separately from the 2040 plan.)

A mid-2000s push for density attracted criticism from the city’s powerful neighborhood groups, who received glowing press in daily newspapers. In 2013, the city rezoned a large area north of downtown, paving the way for Amazon and other tech companies to expand into the neighborhood. The backlash against it still echoes in NIMBY critiques.

And in 2015, into the fray came an early version of the plan. Crisis-level housing shortages were forcing change. While Minneapolis boomed over the last decade, its growth rate was about half that of Seattle’s, where the median house was going for over half a million dollars.

PhilAugustavo / Getty Images

Unlike Minneapolis, Seattle had maintained prohibitive restrictions on building mother-in-law cottages and other, smaller forms of density. The word YIMBY was just entering the local lexicon, and while the city had pro-density advocates, the sort of big-tent political organizing didn’t really start until after the outlines of the plan were public.

And there were grumblings about that process. An advisory committee’s recommendation to eliminate single family zoning altogether was leaked to the press. As in Minneapolis, opponents howled that the bulldozers were coming. NIMBY messaging dominated neighborhood councils and lawn signs.

“You can’t just come out with policy recommendations that you believe to be correct,” one local political operative told the Seattle Times. “You have to go out and organize to persuade people that your recommendations are right for them and our future.”

Unlike in Minneapolis, dramatic change was quickly walked back. As Roger Valdez, a density advocate and developer lobbyist put it to the Seattle Times, “None of [Seattle’s politicians] will stand up and agree that we need to make significant changes going forward.”

Early opposition and byzantine policy hurdles dragged out the process of incremental reforms. “We did more than a year of public outreach,” Johnson said. “We then did one year worth of environmental work. We then were litigated for one year. And then, it took us another six months once that litigation was completed to finally get the bill across the finish line.”

Because of that, there were consequences to taking an early stand for density. “I think it took somebody who wanted to focus on zoning reform, but didn’t care about their political future,” said Johnson, who had always planned to serve for only a single term, but who vacated soon after the plan went through. Opposition to affordable housing, bike lanes, and other measures to manage growth run strong in his district and Johnson believes that he would have faced a serious challenger for his seat if he ran for another term.

Still, by 2018, Seattle’s YIMBY coalition had found its voice. Supporters showed up to meetings and citywide, public support for zoning for density was high (48 percent of respondents in favor; 29 percent opposed). Malaba, who coordinated between pro-density neighborhood, environmental, and labor groups, said the key was “focusing on people who are supportive, but don’t have enough information.”

But building broad support for the plan also meant compromising. Just before its passage, the council proposed a flurry of amendments, scaling back some changes, expanding others, for a net loss of areas that would have been zoned for greater density. According to Councilmember Johnson, that “allowed the council to take a 9-0 vote on a controversial plan.”

The plan is now a platform for further change, Johnson said. Of the dozens of candidates in Seattle’s current city council election, only one front-runner — seeking to replace Johnson — has been vocally critical of the zoning update. The majority support further changes.

Minneapolis organizers’ strength was translating a lofty goal into a conversation that anyone in the city could join, said Calvin Jones, an organizer with Seattle’s pro-density Tech 4 Housing.

Seattle’s plan is “a real momentum builder,” he said. “You saw seven city councilmembers reference doing something more. I don’t think they would have said that if it had just squeaked by without support.”

There’s natural support for creating a denser Seattle if that means more affordable housing, Malaba thinks: “Everyone used to have a neighbor or a friend who’s not here, and more people are being pushed out of the city.”

The real work wasn’t necessarily convincing the other side, Malaba said. It was persuading enough people that changing some thing as dry as zoning codes could have an outsized influence on their homes, their neighbors, and their booming city.