The national and international recognition for the “heroes” of the Flint Water Crisis continued Monday as LeeAnne Walters was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize.

Each year, the prize recognizes the efforts of grassroots activists from around the globe. The selection committee hailed Walters for her dogged determination in testing the lead-contaminated water that was poisoning her children, as well as spearheading citizen-led water-quality sampling “to not only expose the water crisis in Flint, but shine a light on the lead water crisis around the U.S.”

The honor is the latest that has been bestowed on one of the three people who the media made the public face of Flint, Michigan, for their efforts in calling attention to alarming lead measurements until negligent state and local officials could no longer ignore the statistics. Walters and Virginia Tech scientist Marc Edwards were recipients of Smithsonian Magazine’s Ingenuity Awards and the National Center for Health Research’s Health Policy Heroes Award. Walters and Michigan State pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha won a PEN America Freedom of Expression Courage Award. Hanna-Attisha took home a $250,000 public policy prize from the Heinz Family Foundation. She and Edwards won a $250,000 Disobedience Award from the MIT Media Lab. Both said they were donating their big winnings to child health efforts in Flint.

Hanna-Attisha even appeared on the TV game show Who Wants to be a Millionaire, where she won $5,000 for a Flint children’s fund, an amount matched by a foundation. She was part of what the show called “Hometown Heroes Week,” dedicated to people who went out of their way to devote “their energies to the greater good without expecting anything in return.”

Walters at a House Oversight and Government Reform Committee hearing with Michigan Governor Rick Snyder. SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images

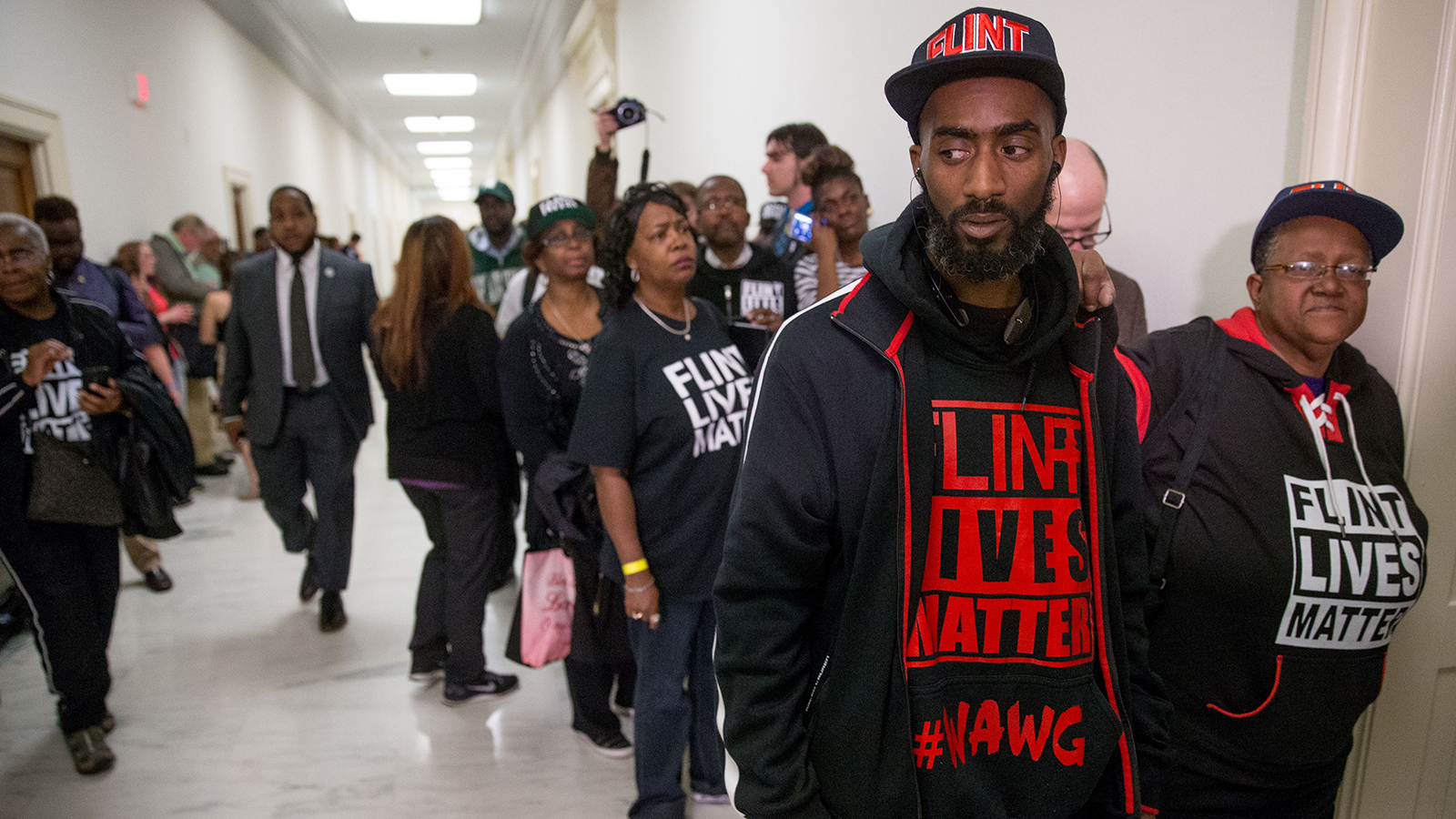

But there is a problem here. For all that Walters, Hanna-Attisha, and Edwards did for Flint — and they justly deserve all the recognition — the awards follow an all-too-familiar pattern. Flint is more than 50 percent black. Yet prizes for heroism have been the exclusive domain of non-black figures (Hanna-Attisha is Iraqi-American). The awards circuit has failed to go out of its way to recognizing and honoring the whole story.

It is the same mistake that the national media made in covering the crisis in Flint, by absentia. I analyzed media coverage in detail for a research paper published last year by the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, part of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. The nation’s top newspapers and television stations came so late to the story that it missed the months of complaints about the water, as well as activism that began almost as soon as Flint, a financially strapped city under state management, switched from Detroit’s water system to the Flint River in April 2014 to save money.

The early actions were covered by local media and featured plenty of black residents, black ministers, and black politicians complaining about the smell, taste, and brown and orange color of the water. One African-American councilwoman, Monica Galloway, even said the city was being treated like guinea pigs and lab rats. Flint did not make national news even when General Motors realized that water from the Flint River was almost immediately rusting its car parts.

As one resident, D’Andre Jackson, wrote in a Letter to The Editor in the Flint Journal that fall:

“Apparently the city of Flint’s water quality is not good enough to be used in an industrial process but good enough to used and consumed by humans … That the water can be corrosive to metal has me questioning whether or not the water is truly safe for me and my family and this community. It’s hard to imagine that this would be allowed to happen anywhere else but within a city like Flint that most politicians would like to write off and forget about.”

As the crisis deepened in the winter of 2014 to 2015, black churches organized bottled-water drives while their pastors helped lead citizens to the state capitol of Lansing to demand that the water be switched back to the Detroit source, Lake Huron. An institute established to transition ex-prisoners back into society organized some of the bottled water giveaways. The institute’s founder, Leon El-Alamin, told the Flint Journal in February of 2015, “There was an overwhelming display of humility and love from those who went to the last giveaway. The cases were gone within 15 to 20 minutes.” DeWaun Robinson, the organizer of another drive, told the Journal, “We are helping on a small scale, but this is bigger than us.”

Robinson’s quote is ironic because his efforts and those of his fellow black residents remained on such a small scale in the eyes of the national media that not a single African-American citizen or community leader was labeled a “hero” by major newspapers or television networks.

As I wrote in my paper:

“No citizens who complained publicly about the water almost right away were cited as heroes, nor were any of the pastors who organized months of protests and marches. Neither were any of the local politicians who took the people seriously early nor any of the community coalitions, local businesses or ex-felons who participated in bottled water drives when Flint was only a local story. Most of the original families who promptly conducted home lead testing remain anonymous.”

In remaining anonymous and absent from the “hero” narrative, the black residents of Flint have not been recognized as possessing the agency of non-black figures involved in the crisis. They figured into the national narrative almost exclusively as helpless or hapless victims, whose woes needed vetting by credentialed, non-black doctors and scientists. It is a type of modern racism that appears in many forms all around us.

America still too often requires a non-black hero or victim before it can turn proper attention to an issue that primarily affects African Americans. The violence in Charlottesville riveted the world because a white anti-racism protester was killed. It took white leaders from Parkland, Florida, for the youth voice on gun violence to reach center stage — after decades of efforts by black teens. The opioid crisis hitting white America hard is largely being addressed as a public health issue, while African-American drug use has long been a problem solved with prison.

The reflex to prop up white heroes saving black people remains prevalent in pop culture. Take hit films, such as Hidden Figures, where a white NASA leader destroys a segregated bathroom sign on behalf of the black heroines, or Black Panther, where a helpful, white CIA agent provides an important assist. (That’s despite the history of the real CIA playing a key role in destabilizing Africa.) In the case of Flint, those giving out awards could have consulted with community groups, such as Concerned Pastors for Social Action, to make sure they understood the full story of the water crisis before selecting honorees.

The cascade of accolades given only to Walters, Hanna-Attisha, and Edwards — as justifiable as they might be in the abstract — are a stark reminder of how America struggles to handle a narrative with African Americans with full agency. Yes, the decorated Flint trio helped expose the crisis. But a lot more people were trying before they succeeded.

Derrick Z. Jackson is a fellow at the Union for Concerned Scientists’ Center for Science and Democracy and a former columnist at The Boston Globe.