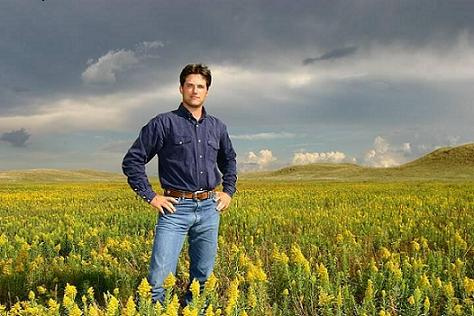

Fresh from an overwhelming primary victory in Nebraska’s U.S. Senate race, 32-year-old rancher, Yale Ph.D., and college history teacher Scott Kleeb spoke with me on the phone about his “brand of change” for a clean energy economy and the environment.

Kleeb shocked the political establishment in 2006 by getting 45 percent of the vote in Nebraska’s 3rd Congressional District, one of the most Republican districts in the country. Then, as now, he ran as a clear progressive on most economic and environmental issues (while staying coy on some contentious social issues).

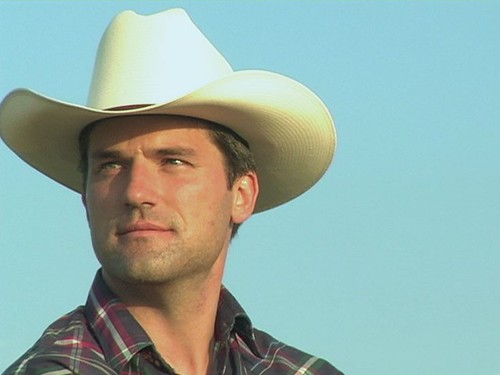

One of Kleeb’s core concerns has been meeting the challenge of the climate crisis through a clean energy revolution on the prairie and through aggressive use of domestic and international forest and farm carbon credits. Through it all, Kleeb has been aided by a huge renewable resource of his own: megawatt good looks that won him “The Hot Rancher” award from Young Voter PAC.

Now Kleeb is hoping his unique combination of deep Nebraska roots, Ivy League cred, and movie star charm will help him overcome his opponent: President Bush’s former agriculture secretary (and former Nebraska governor) Mike Johanns, who’s based his career on support for Big Ag, free trade, and fossil fuels.

Q. Where do you see Nebraska’s economic future, and what role do you think clean energy will play in it?

A. We’ve got to transform the way we produce and consume energy. There’s a failure of leadership we’ve seen at all levels of government. We’ve got to figure out how to do more with less. That’s true of our elected officials and true of ourselves as individuals. This is a generations-long process. We are on the cusp of it right now. Biofuels and wind energy and solar energy and algae-based energy is just the tip of the iceberg.

Nebraska’s economy is going to be transformed by that revolution. Farmers will find new ways of feeding or, once we get to cellulosic ethanol, fueling the world.

Q. Recent studies have suggested that devoting American land to growing biofuels instead of food is causing massive deforestation in carbon-rich tropical forests. How can switchgrass and cellulosic ethanol be viable if it’s just causing food to be grown in these highly sensitive ecosystems thousands of miles away?

A. The rainforests are the world’s largest carbon sink. The impact [of deforestation] there is much more important than what we’re talking about in this country. You saw it in the farm debate on what we do about Conservation Reserve Program land [agricultural land that’s set aside for conservation purposes]. You’re even seeing an internal battle. Many farmers are members of the Farm Bureau or the Farmers Union, but are also members of Ducks Unlimited or Pheasants Forever. On one side, they’re being lobbied by their farm organizations who talk about $5 [a bushel] corn or $6 corn and talk about how great it is and how we should produce more of it. On the other side, they’re being lobbied by the organizations they’re members of like Ducks Unlimited talking about increasing the CRP acreage. Farmers are personally conflicted about it. That’s only going to get bigger. These are not easy questions that we’re trying to deal with.

The advantage of switching to switchgrass is that you can do it because you don’t harvest it the same way you harvest soybeans or corn or other row crops. You don’t have to plough up the ground or disrupt the soil. With switchgrass, it’s a little bit like mowing your yard. You never actually dig the roots out of the system. You never actually turn over the soil in any way, you just sort of mow off the top part of it. You don’t actually disrupt the soil underneath it. You can raise switchgrass in areas we now consider marginal lands, low water lands so that it would not be competing with the river systems like the Mississippi or the Platte or some of the Corn Belt states where they do have a lot of rain or wherever it might be. You’re competing on a different set of areas than you would be for food production.

Q. You talked a lot about carbon sequestration. Could you talk about how that fits into your vision of a new energy economy?

A. We’ve got to not only work on the production side. We’ve got a tremendous amount of carbon. We talked about the sink of the rainforest. We’ve got to discourage taking down of the rainforest as well as our trees in this country. There should and can be sequestration. The Chicago Carbon Exchange should be built up much larger so that companies can begin to invest. It’s also benefiting farmers and ranchers as they embrace the notion of not tilling their land and getting a carbon credit.

But we need to also encourage business to capture some of that CO2 and return it underground. I don’t understand the science as much on the potential of sequestration, but there’s no doubt we can actually find a way to take out the CO2 from the top of a smokestack and find a way to sequester it once we’ve done so. I know there’s been work done to pump it underground or otherwise neutralize it.

Q. But these coal carbon-sequestration techniques haven’t proven cost-effective.

A. The cost of not doing anything about the CO2 in our atmosphere is far greater, so we’ve got to work on it.

Q. A lot of environmentalists say it’s a lot easier and cheaper to invest in efficiency, clean energy, biological carbon sequestration than continuing our reliance on the dirtiest source of energy of all, coal. What do you think of coal’s future?

A. I think that there is going to be a part of coal in the equation for a long time and there are cleaner ways of burning it. But I’m all about the other stuff, too, if we actually challenge industry and challenge ourselves and if we talk about green-collar jobs. When we talk about the potential of green-collar jobs, it’s not just a farmer out here in Nebraska, it’s not just a person building a cellulosic ethanol pipeline across our country, not just someone rebuilding infrastructure for train travel because it’s more efficient, it’s not just a way to produce energy more efficiently; it’s all of this. The spin-off from this is fantastic. It’s beyond what we can actually imagine.

Coal is going to be a part of it because there’s going to be a lag time. A magazine like yours, Grist, has a tremendous advantage and we have a need for it in its ability to think long term. Coal is something we’re going to need in the short run. Longer term, I’m all about the other stuff. I’m about the stuff we haven’t even thought of, Glenn. I’m about the fact that a few years ago we weren’t even talking about algae, but now we are. You put scientists and engineers to work and ask them hard questions and let them figure it out. It’s great.

Q. What mix of technologies would you like to see?

A. I’ve done a lot of work in the field with the environmental community and the agricultural community and was actually hired by the Natural Resources Defense Council to work on climate change and agriculture. We have the theoretical wind potential to supply the world’s energy needs 15 times over. Although that’s just theoretical, you’re still talking about major potential from wind. Where does Nebraska fit into that? We’re the sixth-biggest state in terms of wind-power potential. Wind is gonna be huge! The remarkable thing is that it goes all the way back to when people first homesteaded. Way back in the 1950s, farmers were using a wind charger and generator for electricity. Now when you drive around, you again see people with their own personal wind-powered generators.

Q. What do you think about the Boxer-Lieberman-Warner climate legislation? [Editor’s note: The bill hit a dead end on June 6.]

A. I’d like to see market forces at play, the involvement of government and individuals at all levels, and a significant reduction in greenhouse gases. With a 71 percent reduction by 2050, this bill is a step in the right direction. The real challenge is that the devil is always in the details. When you talk about allocating the type of money that’s going to be generated from a carbon cap-and-trade system, there’s going to be a big impact on [lower-income] families. I’ve got them in my state. My neighbor was evicted from her house because she couldn’t pay her fuel bills.

What do you do for families who can’t afford a $3 or $4 lightbulb now because they’re deciding whether to eat or buy medical care, so they continue to buy their 60-cent incandescent lightbulb? While we all believe in climate change and that we need to do something drastic to fix it, we also can’t increase the numbers of poor people in this country, and we have. In the last seven years, the numbers of poor people in this country have gone up because of the Bush administration. We need to do whatever we can. The short answer is that I like [Boxer-Lieberman-Warner]. I’m for a bipartisan agenda that looks at a cap-and-trade system that reduces our impact on this planet, and that has to start happening.

Q. Is there a certain threshold of reductions in greenhouse gases that you’d like to see? Most scientists have said it’s necessary to have an 80 percent reduction by 2050 if we’re going to avoid the most serious consequences of the climate crisis.

A. Well, then, that sounds pretty good to me. It’s high time we started to look at the science again … Let’s start listening to the scientists again. You know, when 99 percent of scientists are saying something, then who am I to disagree with it? I have a Ph.D., but it’s in history.

Q. Urban agriculture and skyscraper agriculture are increasingly popular ideas because they’d offer ultra-energy-efficient, ultra-land-efficient ways of producing our food. What do you think about this technology and whether it could transform much of Nebraska once again into a giant wilderness?

A. There are fewer people living in many counties here than when we had sustainable localized agriculture. When food becomes localized, then we are going to have to find ways to maintain our economy. The way we’re living is not exactly energy efficient. The way we live is going to change. I don’t necessarily think what we’re talking about is an ultra-urbanization here. Many of these smaller towns have the potential of getting repopulated.

Q. What inspired you to start working on environmental issues?

A. The most obvious is that I have two little girls … [E]ach of us is asking, what type of world do we want them to inherit? If we do something [to avert] the doomsday scenario, if we think about the upside of the world they could inherit — not just environmentally but economically and in terms of national security too — we’ve got to diversify the energy supply in this country so we’re more able to withstand system shocks. Right now, we’ve got a system shock on oil and we’re tied specifically to oil, which is why it’s had such a tremendous impact across our economy. Think about the security they’ll have in both their food supply and energy supply if we get to a sustainable food production model where it’s much more localized production, and things she could potentially inherit and if I could work toward those things and I could help her to get those things and to live and operate in that world, then I have to. It’s as simple as that.

Where does this come from? It comes from my parents taking me out. My dad and I used to hike around the mountains for weeks on end. Living outdoors, going hunting, enjoying sitting by a river. I went around for more than a year and visited every national park and monument west of the Mississippi in my pickup. When you’re sitting there in Glacier National Park and the guy is telling you that there’s not going to be glaciers in 20 years — it’s a bit of a problem.

That trip was fantastic. I lived in my pickup, which wasn’t that carbon friendly, but just slept in the back of it. I built some shelves in the back. I just had a topper in it, not a camper or anything. I was doing research on the cattle trade in the late 19th century American West [for my Ph.D. thesis]. It was about foreign capital coming in and setting up these big ranches we all know from the period of the cowboys.

I set off from Connecticut for the trip, but before I left I spoke with [Yale professor] Robin Winks about it. I said, “Robin I’m getting ready to go on this trip. For every day that I spend in an archive or library, I’m going to spend a day in a national park or monument.”

“That’s great,” he said, “but make it two days … no, make it three days.”

Q. Outside of energy and climate, what do you want to achieve for the planet?

A. Water is an increasingly important resource. We have whole river systems in our country that are important. The potential of oceans in biodiversity and what can come from them in medical research and science. Our oceans and our water systems are something that we need to focus on.