Beneath our feet there is an invisible ocean. Within the cracks of rock slabs, sand, and soil, this water sinks, swells, and flows — sometimes just a few feet under the surface, sometimes 30,000 feet below. This system of groundwater provides a vital supply for drinking water and irrigation, and feeds into rivers, lakes, and wetlands. Across the globe, it contains 100 times as much fresh water than all of the world’s rivers and lakes combined.

As Earth warms, groundwater — long seen as an immutable resource — is in flux. Most often, climate change is associated with a decrease in groundwater, fueled by worsening drought and evaporative demand. But in some areas, this water is actually creeping higher, thanks to rising sea levels and more intense rainfall, bringing a surge of problems for which few communities are prepared.

Places in the United States where the water table is inching higher — along the coasts, yes, but also inland, in parts of the Midwest — are already beginning to experience problems with infrastructure. Cracks in aging and poorly maintained pipes are being inundated, leaving plumbing unable to carry away stormwater and waste. Pavement is degrading faster. Trees are drowning as the soil becomes soupier, starving their roots of oxygen. During high tides and when it rains, groundwater is even reaching the surface and forming temporary ponds where there never used to be flooding.

This phenomenon — groundwater rise — could also have dire effects on people’s health, exposing them to new or unearthed pollutants. In the San Francisco Bay Area, rising groundwater threatens to spread contamination that can evaporate and rise into the air inside homes, schools, and workplaces. In Beaufort County, South Carolina, it is flooding septic systems, leaching raw sewage into nearby waterways. Along the Vermilion River in Illinois, it is seeping into unlined pits containing coal ash — a hazardous waste — and carrying heavy metals into drinking-water aquifers.

These three communities, profiled below, demonstrate the risks that other parts of the country may soon face as climate change alters a system long taken for granted.

West Oakland, California

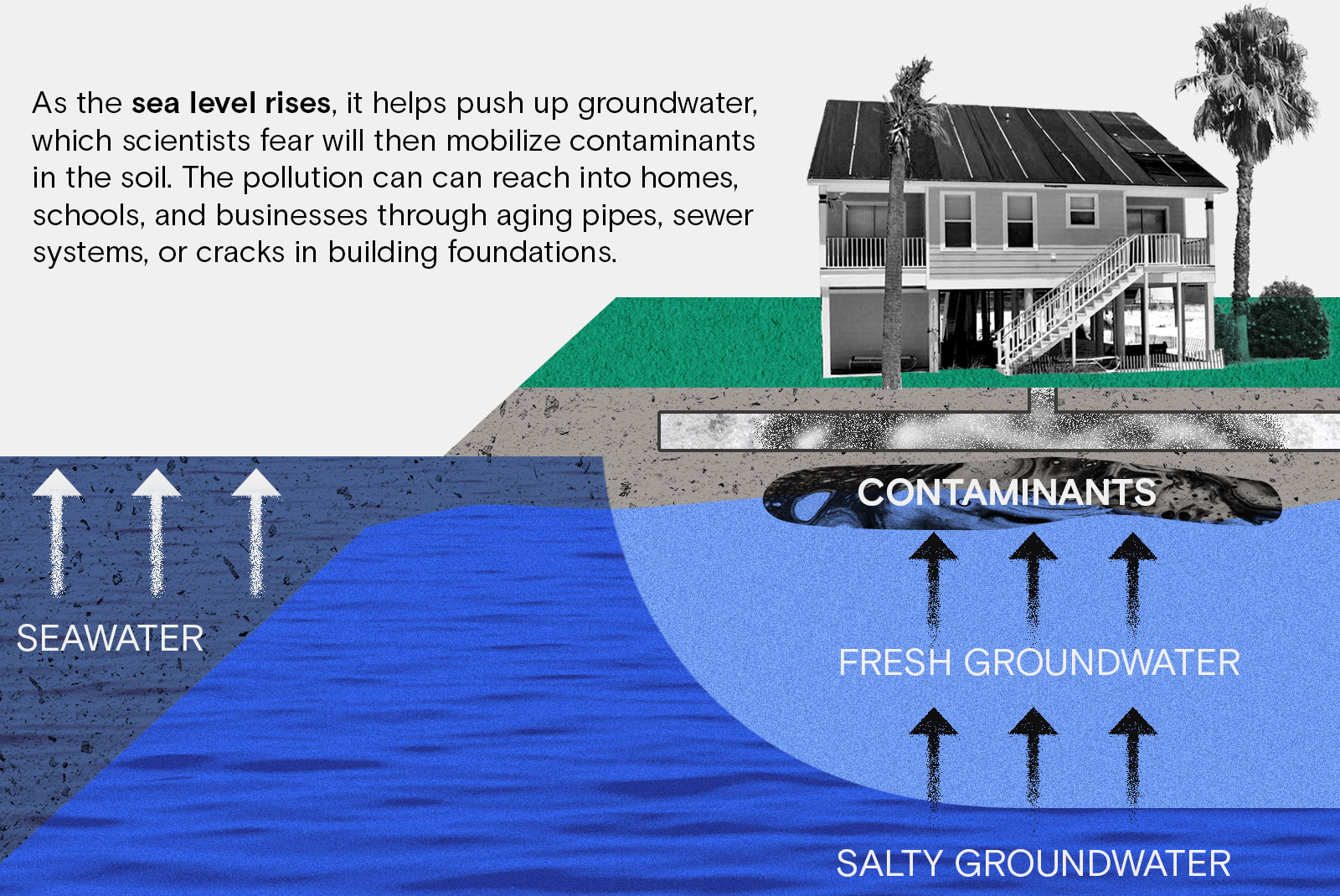

Oceans do not stop where the sea meets the shore. Along the coasts, saltwater creeps through porous soil and rock, creating an underground saltwater table that can extend miles inland.

Many Americans are familiar with sea-level rise. As we crank up the planet’s thermostat, the melting of glaciers and ice sheets and the thermal expansion of seawater mean the oceans are rising and intruding farther and farther inland — both on top of the land and underneath it.

Few regions expect an inundation from below, explained Kristina Hill, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies rising groundwater in urban coastal areas. “They think that building a levee is going to protect them from rising seawater. But, of course, a levee doesn’t affect much about the way that groundwater rises behind it.”

One of many concerning possibilities is that rising groundwater will mobilize contaminants that have been lurking in the soil for years, left behind by industrial and military sites, and allow them to spread, unnoticed, beneath our feet.

Phoenix Armenta has been working to educate communities around the San Francisco Bay Area about this threat for years. In February 2020, McClymonds High School, which is not far from where Armenta lives in West Oakland, was forced to close for several weeks after a cancer-causing chemical called trichloroethylene, or TCE, was found in the groundwater below the school.

West Oakland — a once-thriving Black community decimated by racist urban-planning practices — has been the site of shipyards, car manufacturers, metal smelters, and a former Army base, and is close to a major port and several highways. It’s unclear where the TCE in the groundwater below McClymonds High School migrated from, but NBC Bay Area reported that the industrial solvent could have come from any or all of five polluting sites within a half-mile of the school, including a metal-finishing shop and a former dry cleaner.

Armenta, who was working for a local environmental justice organization at the time, was deeply concerned, but not surprised, by the news. “That entire school is surrounded by toxic sites and toxic contaminants,” they said.

Hill said that rising groundwater could have played a role in transporting the TCE from a contaminated site to below McClymonds High School. U.S. Geological Survey modeling shows that groundwater levels in West Oakland are already climbing, meaning more contamination is likely on the move in parts of the city. But it’s difficult to link specific instances, like what happened at McClymonds High School, to changes induced by rising seas — that would require more monitoring wells to track groundwater levels at a granular level and to map the flow of contamination.

Contaminants that have a gas component, like petroleum products and solvents, are particularly dangerous because they can wind up in the air people breathe. These substances can enter sewage systems through cracked pipes, evaporate, travel up into buildings, and then seep into homes, schools, and workplaces. They can also enter directly through cracks in building foundations.

The California Department of Toxic Substances Control conducted testing and found that TCE was not present in the air inside McClymonds High School. Eventually, the agency allowed the school to reopen, but that doesn’t mean the risk has gone away. As groundwater in West Oakland continues to rise, scientists and activists warn that more contamination will spread, and the risk of hazardous substances seeping into homes, schools, and businesses will grow. “It’s likely to be a hot spot where these things will happen early,” Hill said.

The communities most at risk are disproportionately people of color and people with low incomes. Racist housing policies, including redlining, have pushed Black Americans, in particular, into low-lying areas that flood frequently and neighborhoods surrounded by refineries, factories, and other sources of pollution. “Now those areas have both polluted soil from military or industrial activities, [and] they also have rising groundwater,” Hill said.

Armenta wants to see better monitoring, and they also want to see the toxic sites remediated. “The businesses that have been polluting in this community should be cleaning it up,” they said. If the sites are left unaddressed, rising groundwater will continue to spread contamination and people will get sick.

Beaufort County, South Carolina

Everywhere you look in Beaufort County, South Carolina, there is water. The low-lying coastal county, which sits at the bottom of the state, is laced with streams and rivers, and flanked by marsh and barrier islands. Sea-level rise is obvious here, according to Larry Toomer, who owns an oyster market and restaurant in Bluffton, a fast-growing town in the southern part of the county. On sunny days, water pools in parking lots, and during the full moon, the high tide overtakes roads.

But Toomer worries about the water he can’t see.

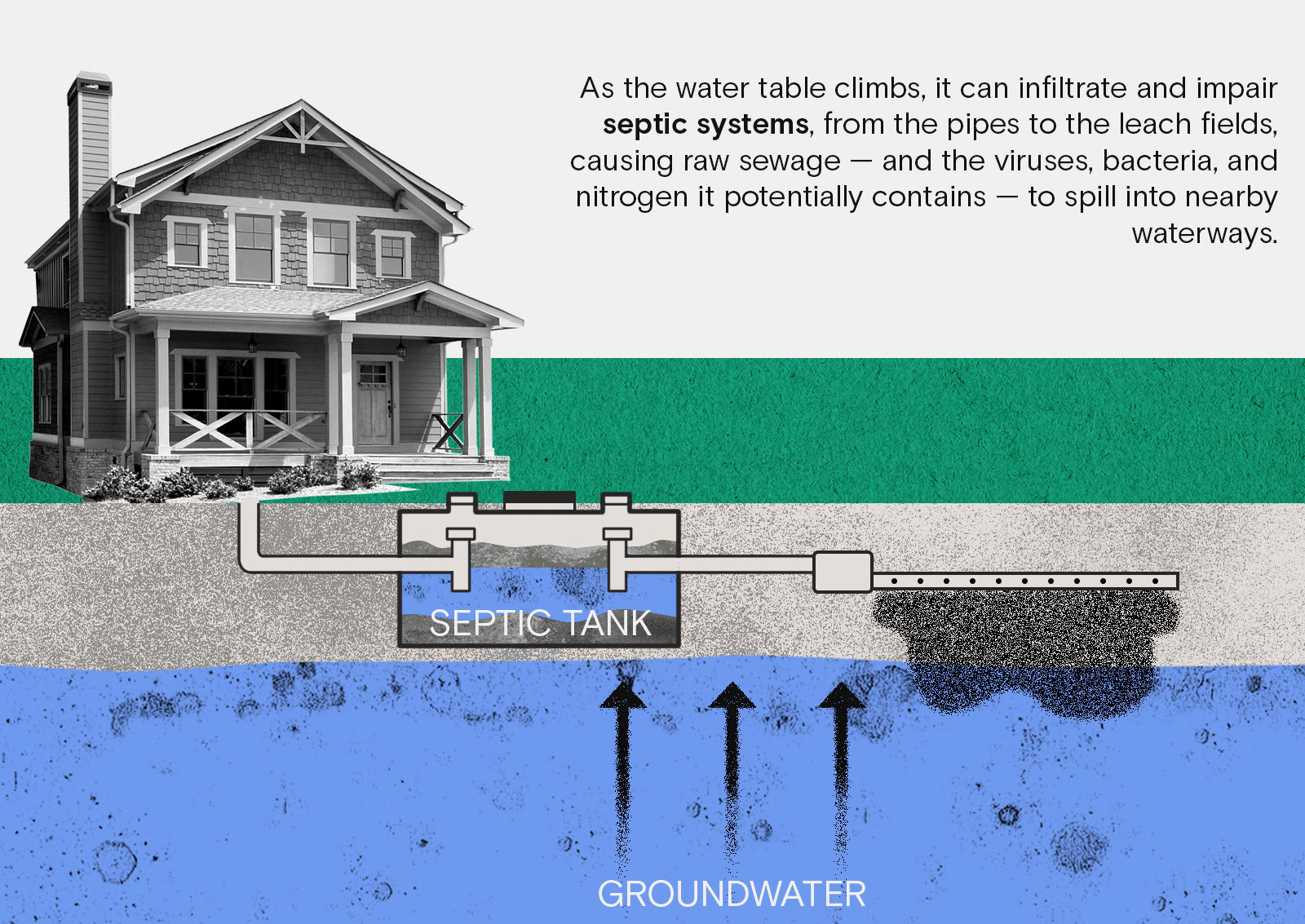

Similar to San Francisco Bay, sea-level rise in this part of South Carolina is pushing water not only up, but inland, raising groundwater levels miles away from the coast. For the rural communities that dot Beaufort County and rely on residential septic systems, this creep spells trouble. As the water table climbs, it can infiltrate and impair septic systems, from the pipes to the leach fields, causing raw sewage — and the viruses, bacteria, and nitrogen it potentially contains — to spill into nearby waterways. It’s an existential problem for a town like Bluffton, where shellfish harvests fortify the economy and residents spend days on the water and nights roasting oysters over the fire. “Without good water quality, you won’t have good seafood,” said Toomer, who serves on the Bluffton town council as mayor pro tempore.

A working septic system depends on the distance between its underground tank and the groundwater below. Waste flows from homes into a tank, where solids sink to the bottom to be eaten by bacteria and liquids flow into a nearby field. There, the wastewater seeps through the earth, where it’s filtered by soil and digested by bacteria. Eventually, clean water trickles into the groundwater.

When rising seas narrow the gap between a septic tank and groundwater, waste can’t be properly treated. Toilets back up, and raw sewage oozes into yards, where it can be washed into surrounding waterways. The fumes can cause respiratory problems, while nitrates may spur algal blooms.

Bluffton is bisected by the May River, which isn’t a river at all, but more like a river-shaped bay, fed by the tides of the Atlantic. In recent decades, extreme rainfall and booming development have eroded the river’s water quality. In 2009, high levels of fecal coliform, bacteria like E. coli associated with human and animal waste, led the state to halt shellfish harvests on the upper third of the river. While fecal coliform aren’t always dangerous, they’re considered an indicator for water quality.

Kim Jones, Bluffton’s watershed resilience manager, said the city has surveyed septic systems, looking for failing tanks. As of last summer, they’ve only found five. “But we continue to get these positive hits,” Jones said, indicative of bacteria being swept into the river when tides below ground encounter groundwater.

Around one in five households in the U.S. rely on septic systems to treat wastewater, meaning they’re not connected to a central public sewer. Rising groundwater will challenge systems up and down coastal areas, particularly lower-elevation states like Florida and Virginia. Communities need to plan for this now, said Molly Mitchell, a coastal researcher at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. “Houses built today, in 30 years, will be in a very different environment,” she said. “Being aware of it could help reduce a lot of future impacts.”

Bluffton is in the process of phasing out septic systems and constructing a community sewer system — a major investment that requires building sewer lines and hook-ups to each home. But many communities can’t afford such projects, or residents may not be willing or able to pay new monthly bills on top of connection fees. Other alternatives — like community septics or above-ground systems — aren’t cheap, either.

Meanwhile, an effort is underway to assess how sea-level rise affects groundwater throughout Beaufort County. Scientists are measuring the height of the water table and how it changes with the tides. That can be used to model what will happen as oceans keep rising or rainfall intensifies. Already, residents complain of pumping out waterlogged leach fields. Alicia Wilson, a project scientist from the University of South Carolina in Columbia, expects that will only become more frequent. “The question is,” she said, “when do things fall apart?”

Such data collection isn’t widespread but will be crucial for helping towns prepare for the future. Rising groundwater is “out of sight, out of mind,” Jones said. But the tides underfoot shape the health, economy, environment, and very essence of her town. “It’s going to be an increasing issue for a lot of communities.”

Vermilion River, Illinois

Inland, far from America’s coastlines, climate change is driving a rise in groundwater levels through an increase in rainfall. Heavy precipitation — particularly when it comes over a short period of time — can cause lakes and rivers to flood and saturate the ground directly. That excess water then percolates down through the soil, raising the groundwater below, explained Mark Hutson, a geologist who previously worked for the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency.

In the Midwest, this change is already underway. As the climate has warmed, the frequency of extreme rainfall events in the region has doubled since the early 1900s. In some places, the resulting rise in groundwater levels from this extreme rainfall — known as “groundwater flooding” — is temporary, receding once the earth is able to absorb the extra moisture. Elsewhere, like in the Great Lakes, steadily rising water levels — which could be up to 17 inches higher on average by 2050 — can permanently change the depth of the water table.

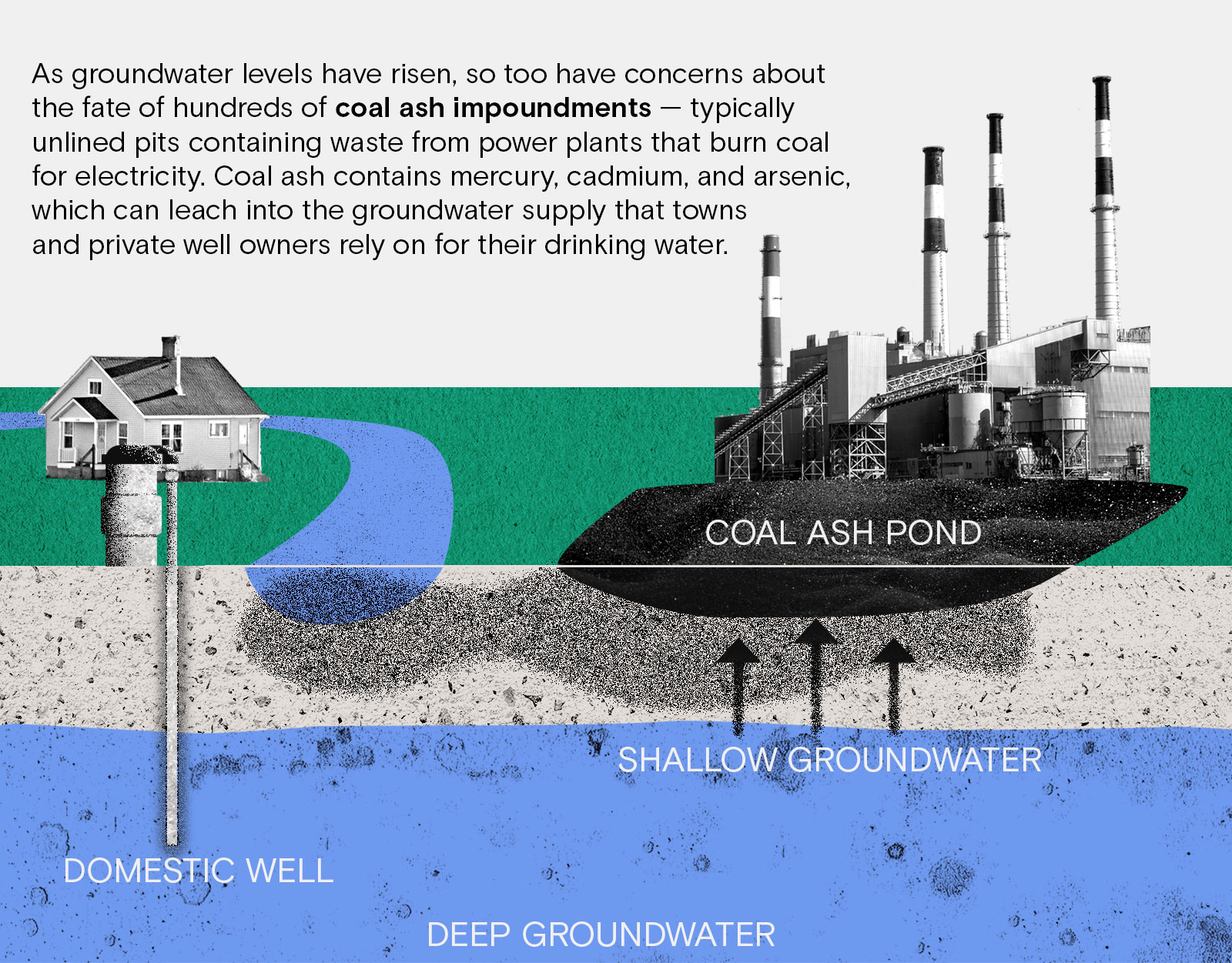

As groundwater levels have risen, so too have concerns about the fate of hundreds of coal ash impoundments — typically unlined pits containing waste from power plants that burn coal for electricity.

Though these dump sites are scattered around the country, they’re concentrated in the Midwest and South. Coal ash contains contaminants like mercury, cadmium, and arsenic, which can leach into the groundwater supply that towns and private well owners rely on for their drinking water. It can also pollute nearby waterways, poisoning plants and wildlife. A 2019 investigation by the Environmental Integrity Project and Earthjustice, which examined 265 coal-fired power plants that monitored the environment around their coal ash dump sites, found that more than 90 percent had already contaminated nearby groundwater with these heavy metals.

At the Vermilion Power Station in central Illinois, which was operated by the Texas-based Dynegy corporation until its closure in 2011, three unlined ponds contain over 3 million cubic yards of coal ash, which has already contaminated the groundwater with boron, arsenic, and sulfate, testing by the Illinois EPA found. And that groundwater has already begun leaching toxins into the nearby Middle Fork Vermilion River; according to a 2018 report by the Illinois nonprofit Prairie Rivers Network, “the riverbank nearest the coal ash is stained brightly orange and has an oily sheen.” The organization has pointed out that groundwater flooding after heavy rains in this region could carry even more pollution from the Vermilion site.

In 2015, hoping to address concerns about groundwater pollution, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency adopted new regulations that required most of the country’s coal plants to stop sending waste to unlined pits and begin closing them entirely. (New coal ash waste has to be sent to lined sites that don’t cut into the aquifer).

That usually meant capping them with a hard shell to prevent rainfall from getting in — but the rules said nothing about the threat from below, said Andrew Rehn, a water resources engineer with the Prairie Rivers Network.

“If you have an ash pond, and it’s got a cap on it, and it starts raining, that cap does prevent that rain from getting in the ash,” Rehn said. “And then you say, ‘Oh, look, it works.’ [But] you’ve ignored groundwater.”

The rules also exempted hundreds of coal ash sites that weren’t actively receiving new waste, but which contain as much as half of the coal ash ever produced in the U.S. Groups like Earthjustice have sued the EPA to force the agency to regulate these so-called “legacy” impoundments.

Under the Biden administration, the EPA has started to look more closely at how groundwater affects coal ash sites. Last year, the agency created a list of 163 coal ash sites with waste potentially located below the water table. Nearly half of these are located in just four states: Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, and Indiana.

Dealing with the problem would require moving coal ash to a landfill that’s “high and dry,” Rehn said. But sites like the coal plant in Waukegan, Illinois, plan to cap and monitor the coal ash instead, despite protests from local communities.

“This is a very urgent issue, because the closure is required, the closure is happening,” said Jenny Cassel, an attorney with Earthjustice who worked on coal ash cases. “And in some places, it’s happening in ways that are not going to alleviate the problem.”

Across the United States

This slow-moving crisis is popping up in communities across the U.S., but there are some common steps that can be implemented anywhere to help stem the spread of contaminants through climate-driven groundwater rise. Hill said one of the most important for government agencies and municipalities to take is simply more monitoring — in particular, at “maximum groundwater moments,” such as a few days after a heavy rain or at a high tide. Currently, sampling tends to be so infrequent that it doesn’t catch the movement of the contamination.

“There are ways that we could be sampling and trying to catch the maximum risk, instead of kind of smoothing it all over with sampling that isn’t related to rain events or tide events,” Hill said. “Ideally, we’d help local people be involved in that sampling so that they know what’s happening in their own neighborhoods.”

Understanding, though, has to be paired with action. Along with taking broader steps to address climate change and its impacts, agencies need to ensure polluters clean up toxic sites, rather than just capping them and hoping for the best.

Mitchell, the coastal researcher in Virginia, hopes that officials will use such data sets to more proactively address groundwater rise.

“I think sometimes when we talk about issues related to changing environments, it can seem overwhelming or depressing,” she said. “But I really think the important thing is that when we have good information about the future, we make better decisions.”