This is part five in a series on “great places.” Read parts one, two, three, and four.

This great place will delight you.

This great place will delight you.

Place enthusiasts (I really need a better term for that) are prone to lapsing into the wonky language of engineers or city planners: transit-oriented development, mixed-use buildings, etc. So let’s not forget, one of the things that makes a great places truly great is simple delight. They aren’t just efficient, effective, and productive; they also surprise us, please us, make us smile or exclaim.

Seattle’s Fremont troll, clearly delighted.If you’re like me, when you think of delightful places you often think of ornamental or artistic features scattered throughout the more pedestrian, pragmatic structures in which we do our business. For instance, almost every Seattleite has been delighted by the Fremont troll. (That’s him over on the right, lurking under a highway bridge and clutching a real VW bug.)

Seattle’s Fremont troll, clearly delighted.If you’re like me, when you think of delightful places you often think of ornamental or artistic features scattered throughout the more pedestrian, pragmatic structures in which we do our business. For instance, almost every Seattleite has been delighted by the Fremont troll. (That’s him over on the right, lurking under a highway bridge and clutching a real VW bug.)

But there’s no reason function and delight have to be separated, as they have been in American suburbs, where a monocrop of beige shopping centers and cookie-cutter houses has taken over. With some imagination, it is possible, even within the bounds of financial rectitude, to make structures that are functional, sustainable, and delightful.

Copenhagen’s Amagerforbraending waste-to-energy plant, not delighting anyone.Consider one of my favorite examples of the last year. Copenhagen is going to replace its 40-year-old Amagerforbraending waste-to-energy plant with a new, bigger, more efficient facility. The Amager Bakke plant, set to open in 2016, will provide the majority of heat and power for Copenhagen with fewer emissions. Still, it’s going to be a huge factory — the tallest building in the city save the Christiansborg spire — and huge factories aren’t typically welcome neighbors.

Copenhagen’s Amagerforbraending waste-to-energy plant, not delighting anyone.Consider one of my favorite examples of the last year. Copenhagen is going to replace its 40-year-old Amagerforbraending waste-to-energy plant with a new, bigger, more efficient facility. The Amager Bakke plant, set to open in 2016, will provide the majority of heat and power for Copenhagen with fewer emissions. Still, it’s going to be a huge factory — the tallest building in the city save the Christiansborg spire — and huge factories aren’t typically welcome neighbors.

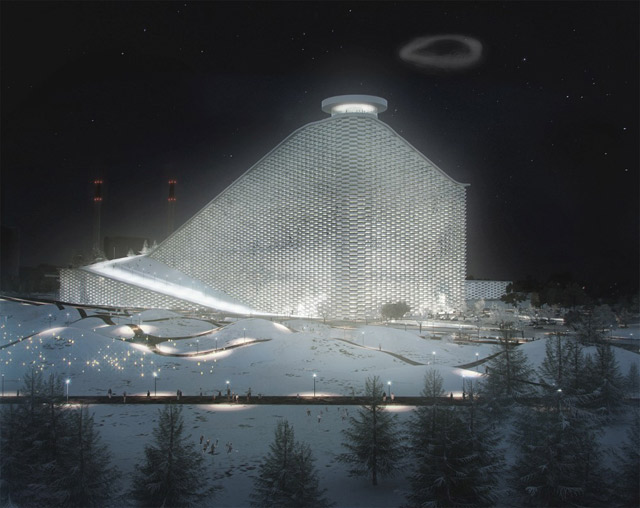

The winner of the high-stakes competition to design the facility was Danish architectural firm BIG, founded by Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, who once described his ultimate aim as “a pragmatic utopian architecture that takes on the creation of socially, economically and environmentally perfect places as a practical objective.”

OK, that’s heady, but … lasers! There are lasers coming later.

Instead of just reducing the plant’s visual impact (a dreary concept, no?), Ingels endeavored offer something delightful. In this case: skiing. An elevator will ascend nearly 330 feet through the center of the building, from which three slopes will be accessible: a green, a blue, and a black run, each of which return to the bottom of the elevator. The idea is to take advantage of the fact that, as Ingels puts it, “we have the snow but not the hills.”

Note the delightful ski bunnies.

Note the delightful ski bunnies.

“When you’re building a big power plant that casts shadows and blocks views in the middle of the city, you normally get a lot of NIMBYs,” Ingels told me. “In this case, we’ve been getting a lot of mail from people asking when it is going to be realized. They are looking forward to it as an addition to their neighborhood.”

(For the record, the snow will not be artificial, but created by capturing rainwater and misting it above an Astroturf-like padding.)

The developer had reserved some money for artistic beautification, but Ingels envisioned something more meaningful. “This power plant will be the cleanest in the world when it’s done,” he says. “It’s going to be blowing very clean, non-toxic smoke. But the smoke will contain CO2. We thought to play with this fact, and be open about it instead of trying to hide it.” So each time the smokestack fills with a tonne of CO2, a disc at the top compresses, releasing a giant smoke ring:

“CO2 emissions are an abstract, uncountable, ungraspable thing,” Ingels says, “whereas now we can make it measurable and visible.”

Here’s where the lasers come in. They will be aimed at the smoke rings, using them to display information about the plant, its emissions, and other energy-related matters. Or, just to make something pretty:

The facade of the building, on the other side from the slope, is also designed for both beauty and function. It will be covered in windows, each ledge planted with with vegetation:

Consequently, the interior will be filled with natural light:

The plant will also contain a visitor center for educational purposes, and be adjoined by open public parks.

Ingels has done other projects to delight the residents of Copenhagen, including a celebrated harbor bath taking advantage of the fact that the city’s industrial port is so clean you can swim in it:

If you head over to BIG’s website, you can see many more such projects (including a killer apartment building for West 57th in NYC) and proposals (including a mindblowing presentation on self-piloting urban cars traveling on solar roadways).

Making places ecologically and socially sustainable “is not a moral dilemma or a political limitation,” Ingels says. “It’s simply a design challenge. We can use sustainability not as a sacrifice, but an upgrade.” He calls it “hedonic sustainability.” I call it making great places.

——

Bonus TED video from Ingels: