Flooding is already the most expensive natural disaster in the United States, costing the country more than $1 trillion in damages since 1980. And it’s only getting worse due to climate change.

A quarter of all critical infrastructure in the United States, 36,000 facilities including airports, utilities, and hospitals, is at risk of becoming inoperable due to flooding today, according to a new report from the First Street Foundation, a New York-based research group.

In addition, 2 million miles of roads, nearly 1 million commercial buildings, and more than 12 million homes are also at risk of being shut down or severely damaged by flooding.

“As we saw following the devastation of Hurricane Ida, our nation’s infrastructure is not built to a standard that protects against the level of flood risk we face today,” Matthew Eby, founder and executive director of First Street, said in a press release, “let alone how those risks will grow over the next 30 years as the climate changes.”

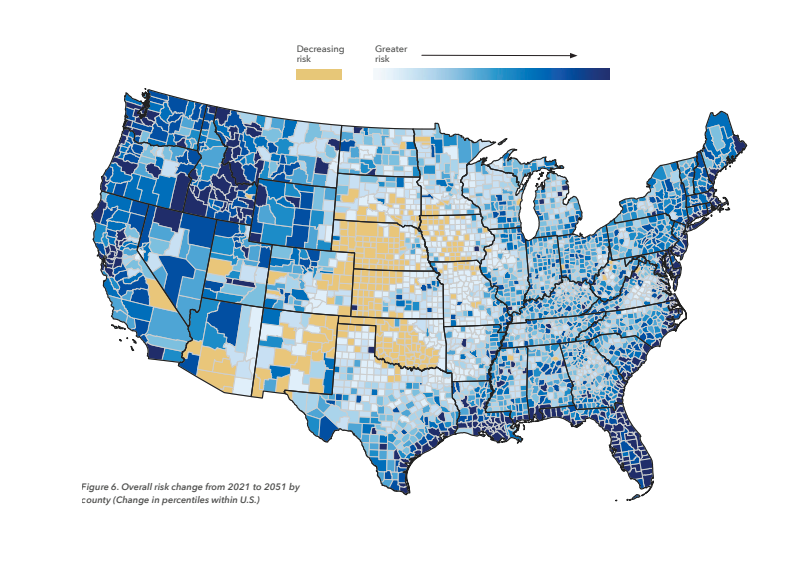

As global temperatures rise, “an additional 1.2 million residential properties, 66,000 commercial properties, 63,000 miles of roads, 6,100 pieces of social infrastructure, and 2,000 pieces of critical infrastructure will also have flood risk that would render them inoperable, inaccessible, or impassable,” the report found.

The research, “Infrastructure on the Brink,” looked at all types of flood risk in every city and county across the U.S. It is the most extensive analysis of its kind to date.

The parts of the country most at risk include the obvious contenders, Louisiana and Florida, but also some not-so-obvious ones: Kentucky and West Virginia.

Alan Fryar, a hydrogeologist at the University of Kentucky, told Grist that low-lying places in Kentucky and the Appalachian Mountains, areas already susceptible to flooding, have become “sitting ducks” in recent years, as rainfall has increased but investment in infrastructure has remained the same.

Along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, flooding is expected to increase due to rising sea levels and increases in storm surge. In the Northwest, flood risk is expected to worsen due to more precipitation, and runoff from increased snowmelt.

“This report highlights the cities and counties whose vital infrastructure are most at risk today,” Eby said in the press release, “and will help inform where investment dollars should flow in order to best mitigate against that risk.”

The report is released amid intense debate in Congress over an infrastructure bill that would provide more than $1 trillion over the next 10 years to fund projects such as making buildings and roads more resilient to climate impacts. Many are pressuring Congress to pass the bill before the end of the month, ahead of the global COP26 climate summit.

“We’re at risk of losing our edge as a nation,” President Joe Biden told Michigan residents last week during a visit to promote the bill. “To oppose these investments is to be complicit in America’s decline.”

This summer was a blatant example of the increasing risk floods pose to communities across the U.S. Hurricane Ida was the fifth costliest hurricane in the nation’s history, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In the aftermath of Ida, floods killed dozens of people in eight different states, left hundreds of thousands without power, and damaged a number of properties.

In areas like Cameron and Orleans Parish in New Orleans, up to 94 percent of critical infrastructure is at risk of becoming inoperable, according to First Street. So when natural disasters like Hurricane Ida occur, local emergency services are almost guaranteed to be overwhelmed, leading to a more catastrophic flood event than if the region had adequate infrastructure.

“Even if local folks are able to repair flood damage to their properties, flooded critical infrastructure may take a longer period of time to build back,” Fryar told Grist. “Water treatment plants, highways, electrical lines — it’s all of that. If that infrastructure hasn’t been maintained, that’s really cause for concern.”