Hello, Nathanael here. Fire season is waning and so are we.

There are just six large, uncontained fires still burning in the West, and even those have stopped growing. There will undoubtedly be more flare-ups before the end of the year, but the fall’s cool, wet weather has dampened fire behavior enough that we feel these weekly updates aren’t quite as useful as they once were. Therefore, we are retiring this newsletter for the season. This week will be our last regular dispatch for The Burning Issue.

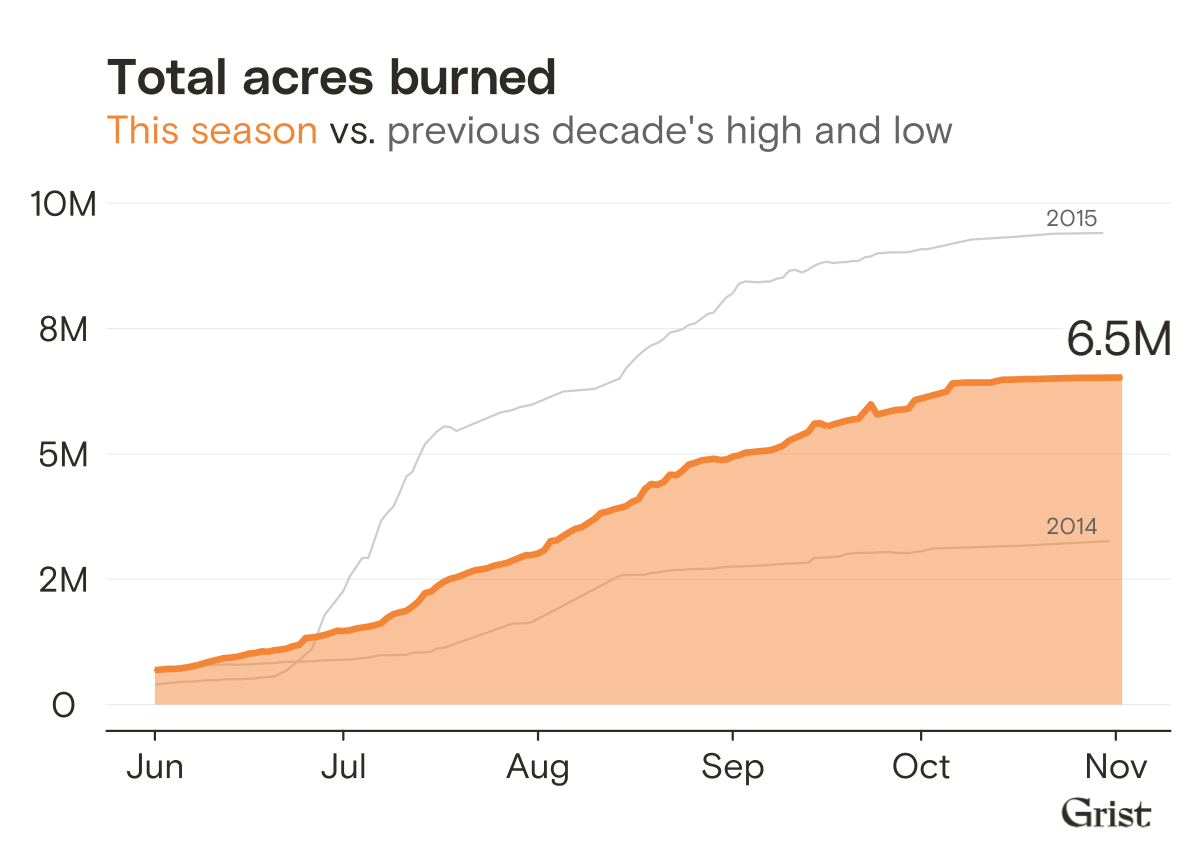

The most striking statistic from this fire season is the price tag: Taxpayers have forked over $4,410,531,182.45 for fire suppression, a billion dollars more than any other year. It’s not because there were bigger fires: The area burned was roughly average for the past decade: 6.5 million acres. The previous record of around $3 billion was in 2018, when Paradise burned in California, and Washington state declared a state of emergency. This season was so expensive because the fires were uniquely fast, powerful, and intense. In trying to protect homes and infrastructure, officials deployed far more firefighters than normal, while also dispatching dozens of bulldozers and calling in helicopters and airplanes.

It’s a situation we could find ourselves in more frequently in the coming years. Climate change is ratcheting up heat and aridity, and every year firefighters stomp out most flames as quickly as possible, leaving more fuel for the next disaster.

The culture of fire suppression is starting to change: There’s a shift underway, from fighting fire to cooperating with fire — allowing both prescribed and wild burns to do the work of clearing and restoring forests. That transformation is likely the only thing that could bring costs down.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

The season through the eyes of a wildland firefighter

Zoya here. For our last issue, we thought you might like to hear from someone who knows fire inside and out. Alexandru Oarcea and I have been friends since we were kids, growing up together in Upstate New York. Soon after college, Oarcea started working for the U.S. Forest Service as a seasonal employee, first as a fuels technician in California. For the past seven years, he’s been part of a 20-person hotshot crew — a type of firefighter trained to tackle the trickiest parts of wildfires — in Arizona.

Shortly after he got back from Arizona this October, we sat down to talk about life in the burn scar, the increasing intensity of fire season, and how governments can better support wildland firefighters.

Alexandru Oarcea

Q. Statistics and news reports indicate that fire seasons are getting worse. But is that what you’re seeing on the ground, too?

A. It’s complicated. Yeah, it’s climate change, but it is also land management and fire management and all the political things that go into it. COVID played a part, too, the last two years. There are also hiring issues: the pay disparity on the federal side, and having a really hard time filling positions.

Q. Can you talk a little more about those shortages?

A. It’s made national news now that [wildland firefighters] don’t get paid very much on the federal side compared to state agencies. That has hurt us because now nobody wants to work for us. At least two or three different times in California and Oregon, [our crew would] be out on the line somewhere and state-employed firefighters would come over and be like, “Oh, we’re making three times what you are.” They put us down just based on pay. It was fucking fascinating.

Q. So what would improve work life for federal wildland firefighters?

A. Biden pushed something through this summer to make the minimum wage $15 an hour. It had been less than that. Most of our money — what makes the work reasonable — comes from overtime and hazard pay. When we’re on a fire, we get a 25 percent increase of our base pay.

But Biden also changed [a policy] this summer that now makes it mandatory to have three days off instead of two after a 14-day shift. We’re pushing for it to be discretionary. That’s a huge chunk of money we’re missing out on. Everybody’s away from home anyway. They’re there to work. On a third day off, they’re just sitting around twiddling their thumbs. Housing is a big [issue] too. Where I work, we don’t have any kind of housing and the rental market is pretty crazy. Half the guys on the crew live out of their cars. So you have two or three days off and you’re still living out of your car.

Q. When you’re protecting a home that’s built in some risky location, like the mouth of a canyon, do you ever get frustrated with people being allowed to build wherever they want?

A. I’m less frustrated with where they build and more with how they manage their property. Nobody living out West in the wilderness-urban interface should be surprised that the fire is going to come. When we show up and there’s a fire coming down the mountain, that’s not the time to use taxpayer dollars to save your house that you had years to protect. Most houses could be fine if you just did a little work, cut back bushes and thin trees a bit. If this trend of busy fire seasons continues, it’ll get to the point where we just evacuate houses and protect public infrastructure: Evacuate people and let houses burn, because we don’t have the capacity to save them all and they haven’t done the work to protect their own place.

Q. Is wildfire season ever truly over?

A. This year’s wildfire season is not over, but the government can’t keep us on for any longer or else they’d have to pay us benefits and retirement. It’s 10,039 base hours — that is the maximum we can work before we become full-time employees. So each region starts at a different time. We start in April down in the Southwest because that’s when our fire season starts. Then we get laid off at the end of September. California crews start later, at the end of May, and get laid off at the end of October and November. But it’s just the rotation of six-month periods. So my fire season is over just because I’ve maxed out how many hours I can work. It has nothing to do with whether there are fires or not. It has to do with money.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Goodbye (for now)

It’s been a true pleasure joining you each week to think through how wildfires are reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems across the U.S. West. Thank you for following along. Our fire coverage isn’t quite over yet — we have a few more in-depth features in the works. We’ll be using this newsletter to alert you when those get published. And if you’re craving more Grist content, sign up for one of our other newsletters here.