Hello and welcome to the first edition of The Burning Issue — Grist’s limited-run newsletter about all things fire. My name is Zoya Teirstein and below, you’ll hear from my colleague Nathanael Johnson. Every week, Grist will send you an email that will arm you with everything you need to know about this wildfire season.

We’ve reached a critical point in the 2021 fire year. Spring and early summer are historically rough in the Southwest, where fires rage early and die out as monsoon season arrives later in the summer. That is when fires in the West normally pick up pace, beginning in August and into the fall. “That’s when shit really hits the fan,” a wildland firefighter told me last year.

That’s where we are now. Federal, state, and local firefighting agencies are stretched extremely thin, most available resources — tanks, planes, buses, helicopters — are deployed, wildland firefighters are exhausted, and the fires just keep coming.

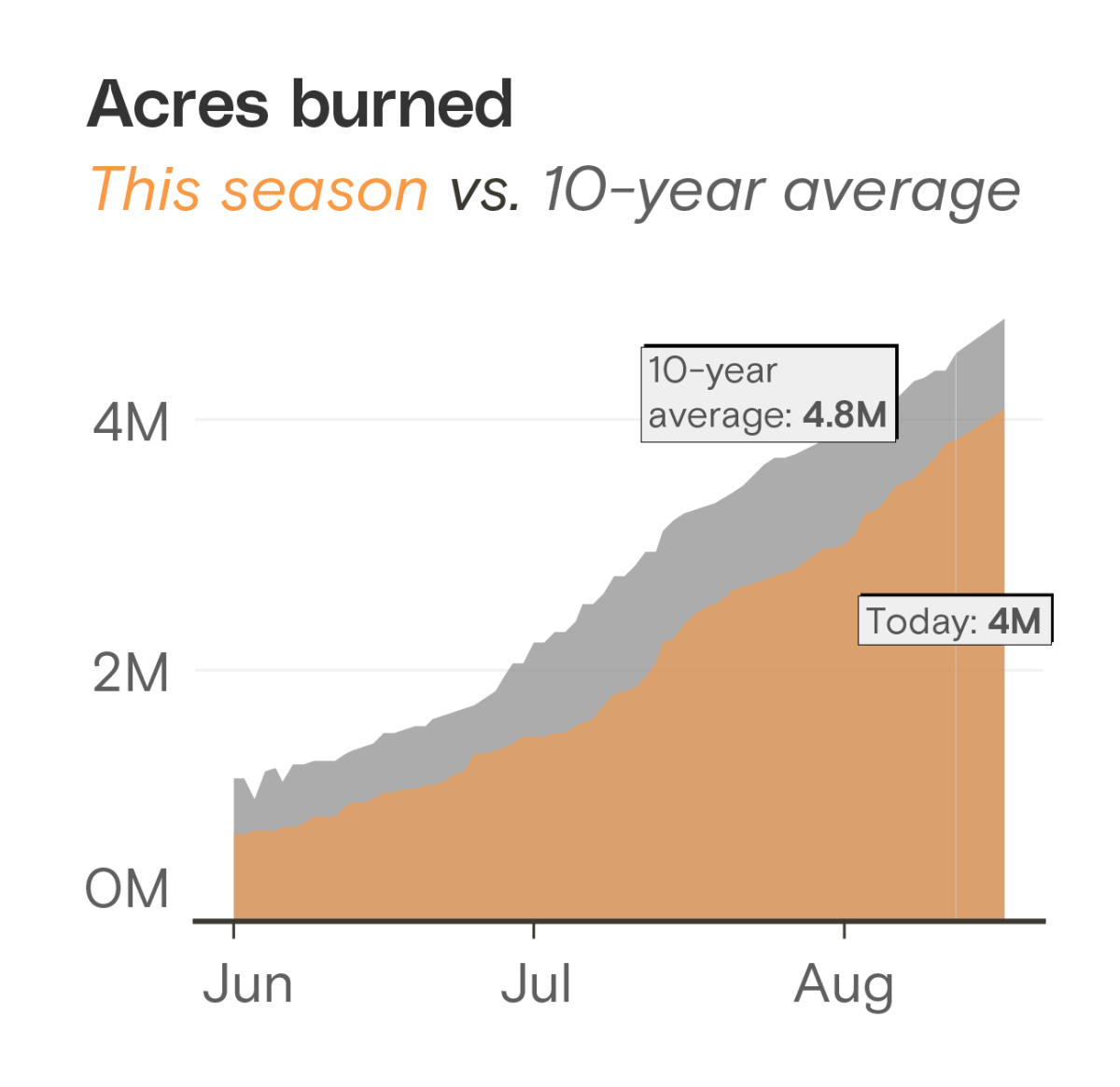

Some 4 million acres have burned so far this year, up from roughly 2.4 million this time last year. There are 104 fires currently burning in 12 states, most of them in Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and California. Just two of those blazes are contained — meaning firefighters have dug or constructed a perimeter around the fire, significantly slowing or stopping its spread. With severe drought conditions and high fuel loads persisting throughout much of the West, forecasters anticipate above-normal fire potential through September.

Howdy — Nathanael here:

Over the years, as I’ve reported on wildfire and forest management, I’ve heard the Forest Service say again and again that it wants to befriend fire, only to end up fighting it. That pattern repeated most recently when the agency’s new chief, Randy Moore, announced that the Forest Service would ban prescribed burns and put all of its resources toward aggressive suppression tactics, due to the land being so dry and firefighting resources being stretched so thin.

The response from some scientists was almost immediate, asking Moore to reconsider. Sure, it’s very dry, they agreed, but local rangers are better equipped with more tools and choices. And a countrywide prohibition makes little sense when, for instance, heavy monsoon rains have drenched the Southwest, substantially lowering fire risk there from scary levels earlier in the year.

The underlying science is clear, they write: “Fire exclusion, along with historic logging that removed larger fire-resistant trees, are in part responsible for our current fire and forest management challenges, with changing climate increasingly acting as a force multiplier.”

Moore already knows this. Back in 1910, the Forest Service saw wildfire as the enemy to be quashed and defeated — every blaze quenched by 10 a.m. As a result, the nation’s fire-free forests filled with dry wood — fuel for more severe fires down the road. But in the 1970s and 1980s, the agency started to rethink its approach to fire suppression. By 2001, Forest Service Chief Dale Bosworth recognized the completion of fire’s transformation from foe to friend, saying, “We’ll light fires where we can and fight them where we must.”

And yet, 20 years later, the Forest Service keeps going back to treating fire as the enemy. Timothy Ingalsbee, head of the nonprofit Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology, told me he’s seen it over and again: “It’s almost a chronic knee-jerk reaction to fall back on this retrograde policy,” he said.

Why? A lot of it has to do with the fact that most of the public still sees fire as more intuitively dangerous than the suppression of fire, Ingalsbee said. If someone allows a fire to burn, and then it wipes out a town, that could end their career. But no one ever loses their job for unnecessarily stomping out a fire. No one will be crucified in the press for allowing dangerous fuel loads to build up. Instead, Ingalsbee said, the public at large will pay for it.

“Now the bills are coming due,” he said. “We are living in the age of reckoning.”