Happy first day of Fall! Zoya here.

A bit of good news out of the West Coast for once: Rain gave firefighters working to suppress blazes in the Pacific Northwest and Northern California a helping hand over the weekend. Crews working the Antelope and River Complex wildfires in California got to hunker down as the weather worked to slow the pace of the flames. In Washington state, Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz lifted a statewide ban on prescribed burning, citing “autumn rains” and “shifting weather conditions.” Rainfall in Oregon aided wildland firefighters battling wildfires throughout the state and has forestry officials hoping that the worst of its fire season is in the rearview.

In less good news, the KNP Complex Fire in Sequoia National Park in California has burned some 24,000 acres so far. It entered the Giant Forest last Friday — the portion of the park that’s home to some of the world’s oldest and most treasured trees. As the wildfire encroached, firefighters wrapped the base of General Sherman — the planet’s largest tree by volume — in aluminum foil to protect it from the flames. The aluminum would have functioned like a second bark for the tree, but the area, which underwent a prescribed burn as recently as 2019, managed to escape the worst of the flames. The KNP Fire, sparked by lightning on September 9, is zero percent contained.

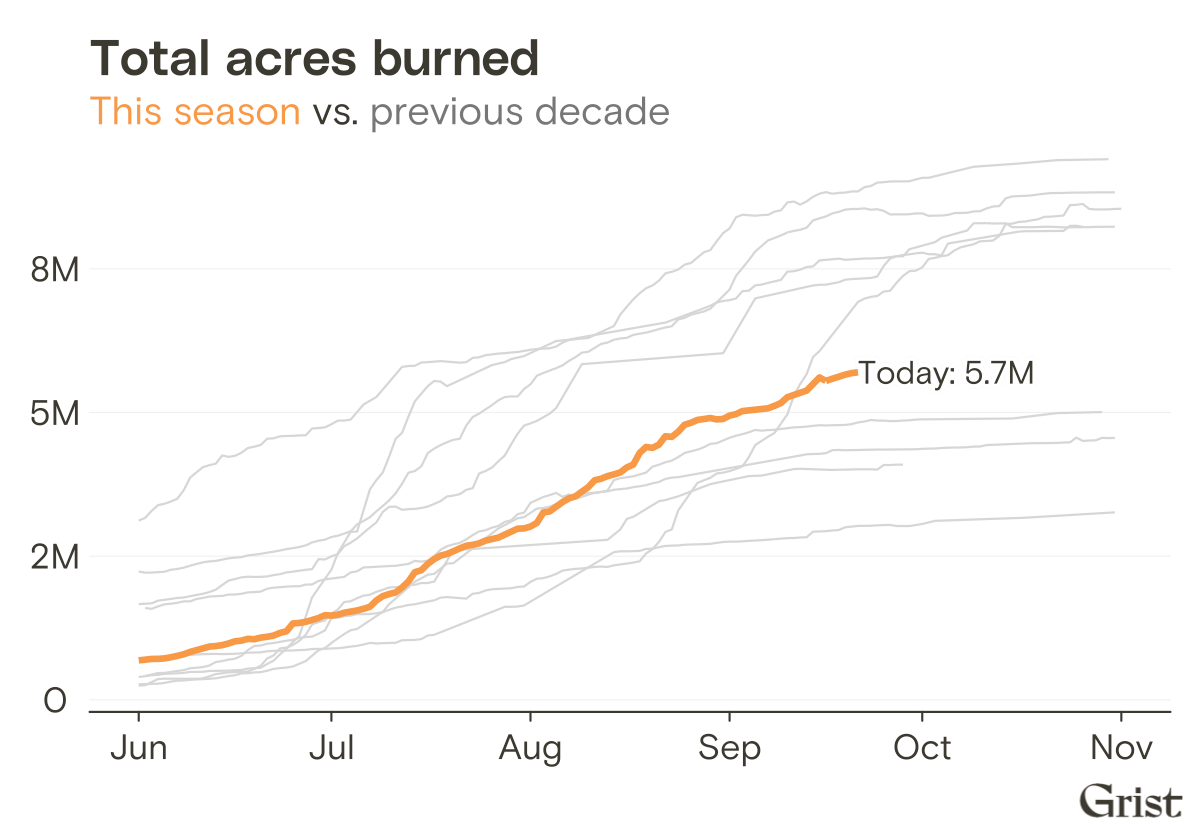

There are 68 uncontained wildfires burning in the U.S. at the moment. Roughly 5.7 million acres have burned so far this year, with U.S. suppression costs adding up to $3.7 billion.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

In California, Indigenous communities get protections for cultural fire practices

Mark Armao here, Indigenous affairs fellow at Grist. I’m stepping in this week to update you on a story I’ve been following.

Earlier this month, California lawmakers passed a couple of bills that will make it easier for Native American tribes to set prescribed burns as a way to protect their lands from wildfires.

Intentional burns have been practiced by certain tribes throughout North America for centuries. The land stewardship strategy is used not only to reduce fuels for wildland fires, but also to aid in ecological restoration, food gathering, and ceremonial activities. In Northern California, members of the Karuk tribe use their understanding of the area to set controlled fires during certain times of the year when wildfire risk is relatively low.

Tribal member Bill Tripp told me he started practicing cultural burns as a child, under the close supervision of his grandmother. But in recent decades, members of the Karuk and other tribes have had to cut back on burning activities, fearing legal retribution or fines from state agencies that have cracked down on unpermitted fires. In some instances, cultural fire practitioners have been charged with arson.

“I haven’t heard of a single cultural burn in our territory ever escaping,” said Tripp, who is the director of natural resources and environmental policy for the Karuk tribe.

Bill Tripp, director of natural resources and environmental policy for the Karuk tribe, stands in tribal land burned by wildfires near Happy Camp, California. Carlos Avila Gonzalez / The San Francisco Chronicle / Getty Images

But as climate change dries out Western forests and wildfire conditions worsen, California tribes have been urging lawmakers to loosen restrictions affecting cultural fire practitioners.

Under current laws, so-called “burn bosses” can be held liable for any firefighting costs resulting from a prescribed burn, which makes it virtually impossible to get insurance for such activities. One of the new laws passed by the California legislature this month, SB 332, would require a showing of “gross negligence” for a burn boss or cultural fire practitioner to be held liable for damages, similar to liability standards in states like Florida.

The other bill, AB 642, would make multiple changes to state law to enhance wildfire prevention efforts, including facilitating cultural burning activities and streamlining the permitting process. Both bills, which are awaiting Governor Gavin Newsom’s signature, introduce new definitions for “cultural burn” and “cultural fire practitioner.”

Tribal leaders believe the new legislation will aid in their efforts to prevent and manage wildland fires, such as the Slater Fire that destroyed nearly 200 homes near the Karuk tribal seat of Happy Camp, California, last year.

“These revisions respect the sovereignty of tribes and the traditional ecological knowledge that people within the tribe hold,” said Craig Tucker, a natural resources policy consultant for the Karuk Tribe. “It’s kind of a turning point where the state is starting to recognize and embrace the need to work with tribes to address the wildfire crisis.”