Hello Nathanael here. It’s Wednesday, October 20, and there is some hope that fire season could be coming to an end.

Autumn rain is falling in the West, quenching fires. This time last week, 45 large blazes burned across the region. Now, just 18 remain: eight in California, and 10 spread across Idaho, Oregon, Montana, and Washington.

In California, where the biggest wildfires burned this year, weather models suggest that enough rain will fall this week to end the fire season — at least in the northern half of the state. There may even be enough of a downpour to flip from a problem of too little water to too much. There’s always a danger of flood after fire. Instead of soaking into the ground, the rain runs off the charred, unabsorbent surface, gaining force as it rushes down ravines and dry creek beds toward homes and roads. When rain followed the 2017 Thomas Fire, mud and debris flows crushed houses near Santa Barbara and killed 21 people.

It’s too early to say if Southern California has seen the end of its fire season. The storms could miss the area, and the vegetation there is still dangerously dry. In 2017, a cluster of major fires, including the Thomas Fire, flared up in December, when most people are more concerned about cold weather than heat.

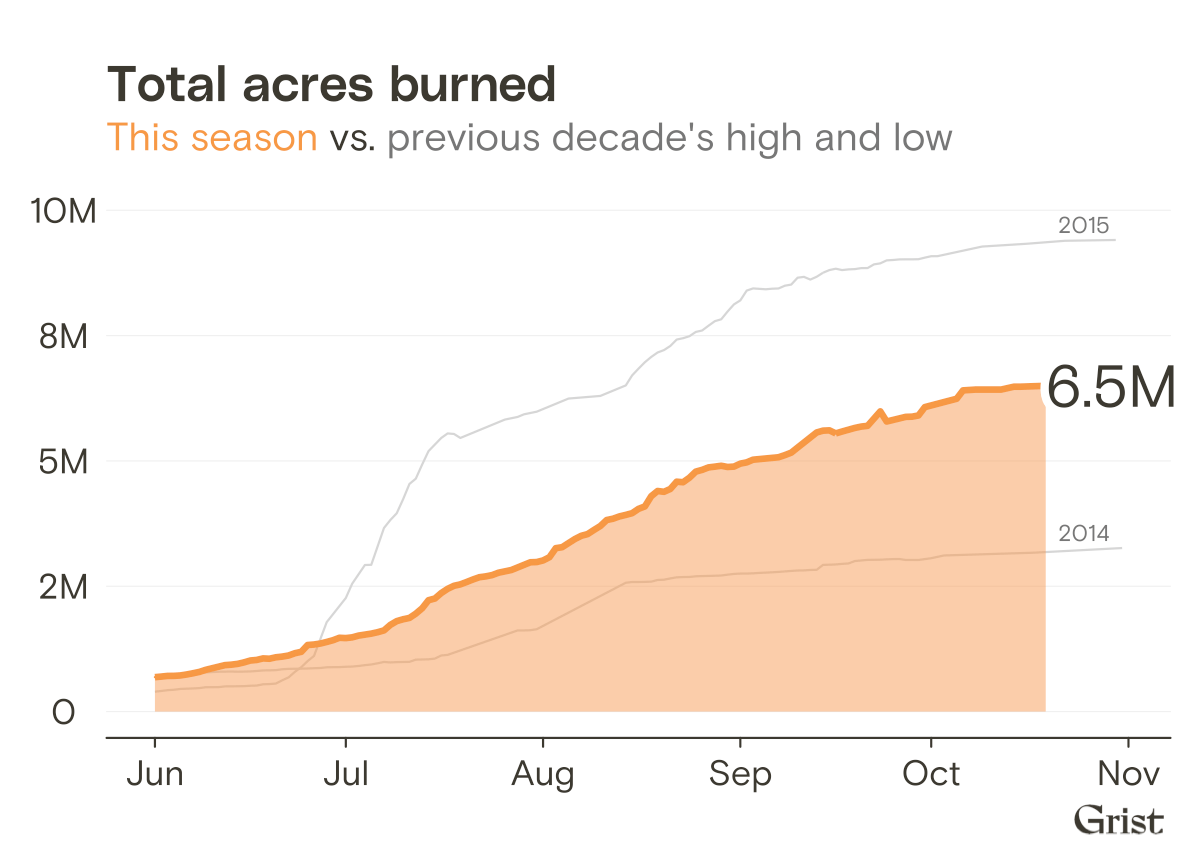

Approximately 6.5 million acres have burned so far this year and fire suppression has cost the U.S. $4.4 billion — already the highest bill ever.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

Forests and fires in the Midwest

Jena Brooker here, Midwest fellow at Grist. Today, we’re moving away from our focus on fires in the American West to explore how Midwestern forests and wildfires are being reshaped by climate change.

In August, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota, one of the most-visited natural areas in the country, made headlines when it was shut down for the first time in nearly half a century due to a series of wildfires. The blazes, fueled by severe drought conditions and strong winds, ravaged the park, burning tens of thousands of acres before being contained in October. The incident was emblematic of a particularly damaging fire season in Minnesota. The state usually sees an average 1,400 wildfires annually. So far this year, it has experienced nearly 50 percent more wildfires (2,025), with almost 70,000 acres burned. At one point, firefighting crews from more than 20 states were working to put out Minnesota’s fires.

A rapidly growing wildfire in northeastern Minnesota that prompted evacuations in August Nick Petrack / AP Images

“The climate is changing, it’s getting warmer, and this fire is a warning sign,” Jim Manolis, forest program director at The Nature Conservancy in Minnesota, said about the Boundary Waters blaze. “We’d expect to see more fires like this with the warming climate.”

Wisconsin, too, faced abnormally dry conditions this year. In April, Governor Tony Evers declared a state of emergency due to elevated fire risk. While wildfires aren’t uncommon in Wisconsin, the season started earlier than usual due to early snow melt, and several of the more than 300 blazes the state experienced this year led to evacuations.

As global temperatures climb, scientists say drought conditions similar to those seen this summer could become more common in the Midwest, potentially leading to an uptick in its number of wildfires. Parts of Minnesota were classified as being in “exceptional drought” this summer — the first time on record that’s happened. Climate models show extreme heat in the Midwest and “insufficient” soil moisture levels will become more frequent in the coming decades.

Not only is the climate changing, but Midwestern forests are, too. Tree diversity has declined, due to human activities like logging and agricultural development. Fire suppression has led to a decline in drought-tolerant species, like oak and pine. Warmer temperatures have increased issues with pests and diseases in the region’s forests. Altogether, a less diverse forest is less resilient to stress events. And a buildup of dead and dying biomass leads to more severe wildfires.

Prescribed burns can help keep forests healthy and fire-resilient. But the practice is complicated in the Midwest, where, compared to West Coast forests, there’s more fragmented habitat that makes it trickier to contain burns.

While scientists agree that the climate and forests in the Midwest are changing, there are still uncertainties as to exactly what the future will look like in the region.

While parts of the Midwest are experiencing more drought than ever before, they’re also experiencing more moisture, according to Amanda Carlson, a forest ecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. But the patterns of this precipitation are changing: Increasingly, rain is coming all at once, during severe events. Such a pattern means that the water doesn’t have a chance to soak into the ground and alleviate dry soil conditions over the long term.

“You have a lot of variability,” Carlson said. “These dry periods could potentially increase our wildfire danger.”