Welcome to the 8th edition of the Burning Issue. Today is Wednesday, October 6. Zoya here.

The battle to save California’s giant Sequoia trees is back on as fires in the Sierra Nevadas ramped up again in recent days. At least 44 of them have been incinerated by the Windy Fire in Sequoia National Forest. Wildland firefighters climbed at least one giant tree to stop some of its branches from burning. Warm weather is drying out underbrush and other flammable material, making it more difficult for firefighters to contain active blazes. The KNP Complex fire, which has ripped through Sequoia National Park, Kings Canyon National Park, and Sequoia National Forest, was 20 percent contained last week, but is now only 11 percent contained.

In Montana, crews are making progress on several large fires, though hot and dry conditions in the first half of this week elevated fire risk in much of the state. In Idaho, which has the second highest total burned area this season, local officials are already breathing a little easier as cooler and wetter weather dampens the fire forecast. The Oregon Department of Forestry declared fire season over on Tuesday for the western part of the state, thanks to rain. Cooler weather is also helping to contain wildfires in Washington.

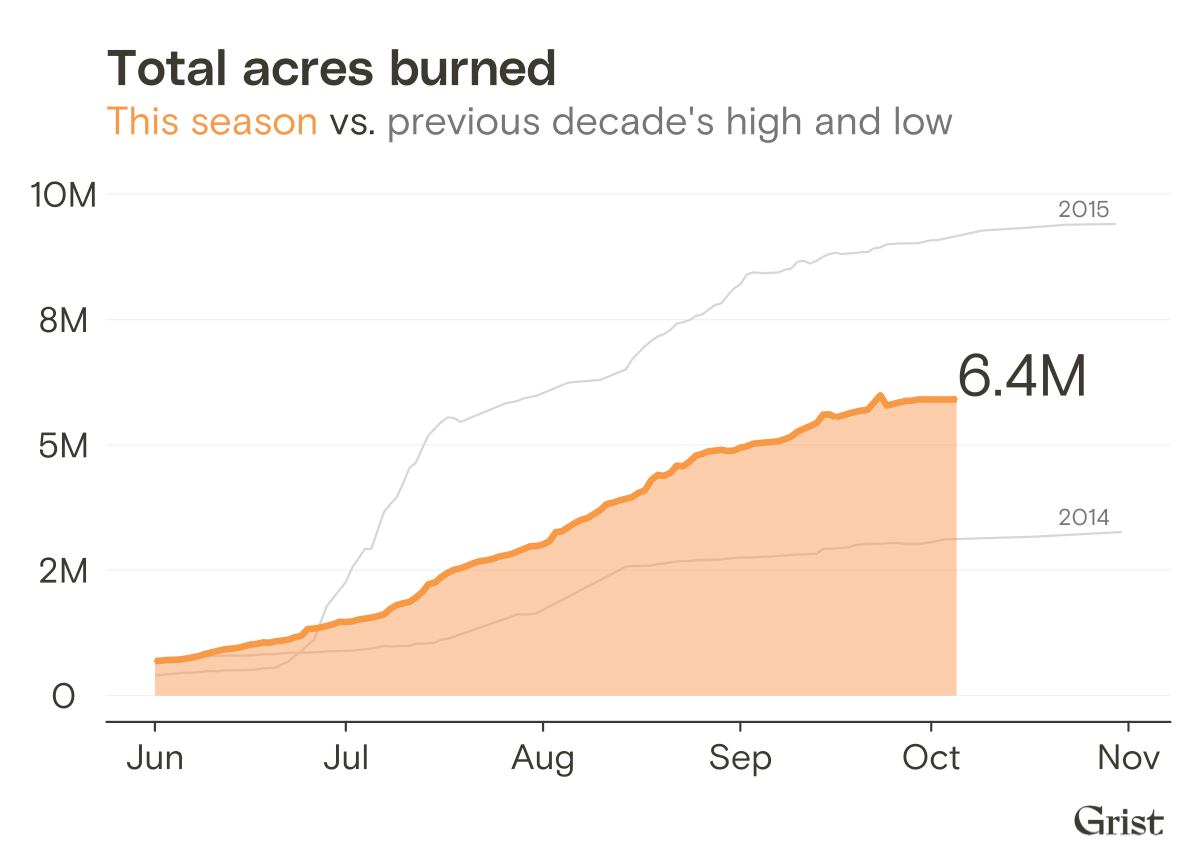

There are 52 large wildfires still burning in the U.S. and 6.4 million acres have burned so far this season. The federal government has spent roughly $4.2 billion on wildfire suppression, nearly equivalent to the annual budget of the entire state of South Dakota.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

How does all this smoke affect the climate?

Nathanael here. Back in July, people woke to oppressive haze — only this time it wasn’t the Golden Gate Bridge that disappeared into the smoke from nearby fires, but the Chrysler Building in Manhattan. Smoke from Western fires had travelled 3,000 miles to blanket cities from Philadelphia to Toronto. It is well-known that fires release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. But there’s a lot more to climate change than just the effects of CO2: Scientists are beginning to understand how all that smoke billowing into the atmosphere every fire season is also mucking up long-term weather patterns.

The primary effect of wildfire smoke is temporary cooling. Anyone who has experienced days of heavy smoke in recent years knows the strange feeling of walking outside into what feels like an alien atmosphere, the sun discolored and the air strangely cold. Sometimes fires inject plumes of smoke all the way into the stratosphere, where particles can linger for months, reflecting the sun’s energy away from the earth. One study suggested that, in total, smoke from forest fires cooled the earth by 0.13 degrees Celsius (0.23 degrees Fahrenheit) between 1997 and 2009.

A pyrocumulus cloud from the Bootleg Fire drifts into the air near Bly, Oregon Ayton Bruni / Getty Images

At the same time, a small fraction of wildfire smoke is black carbon particles, which, instead of reflecting the sun, absorb its heat and increase temperatures. When black carbon particles settle onto glaciers, they accelerate melting because they turn a white reflective surface into a dirty grey heat magnet. The soot discoloring glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau, for example, has accelerated melting by 20 percent, according to a review of the scientific literature.

And then there’s the way that smoke interacts with clouds. It tends to suppress precipitation, which could increase the severity of long-term droughts, leading to bigger fires and more smoke.

How do all these effects work in combination? The best scientists can do right now is respond that it depends on the circumstances. Smoke is definitely changing the weather, and the long-term climate too, but we don’t know the full extent yet.