There is a common perception that electric cars are really expensive. It isn’t helped by media fawning over the high-end Tesla Model S, which has a base price of $71,000. But most EVs cost much less than that, and measured over a five-year span, the total cost of owning and operating the more affordable EVs can actually be lower than the cheapest gas-swilling econo-boxes.

Edmunds.com, the “car buying platform” that tracks auto sales with obsessive detail, calculates the “True Cost to Own” or TCO for hundreds of models. “In many cases,” it writes, “TCO points buyers toward an unexpected conclusion: Sometimes the cars that are cheaper to buy are more expensive to own.”

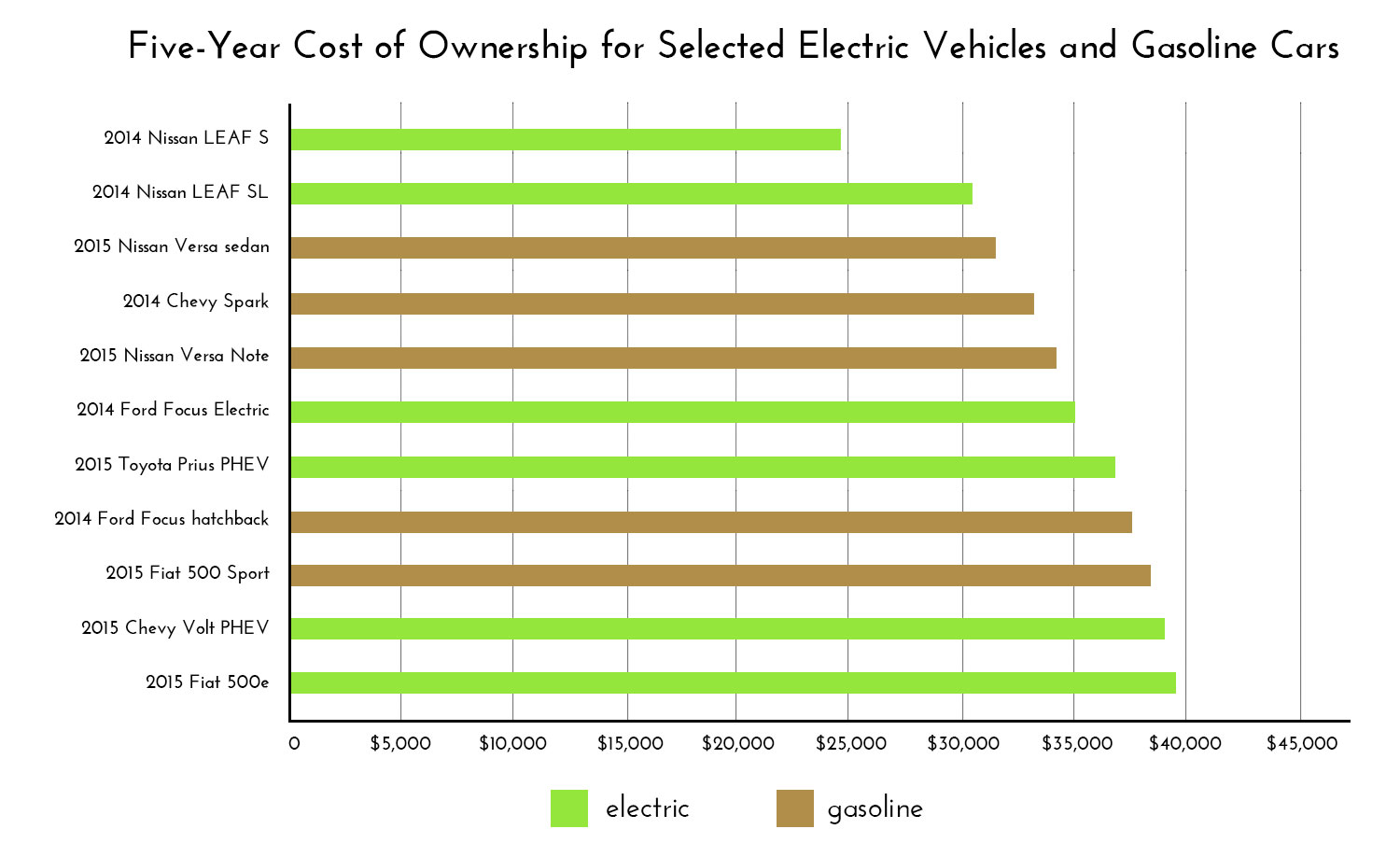

According to Edmunds data for my zip code, here’s how popular electric cars compare with a few standard economy cars over the first five years of ownership:

Let’s dig into the numbers a little. For starters, you should know that the average selling price of a new car in 2014 was $32,618, according to the National Automobile Dealers Association. The sticker price of many electric cars is at or under that average, even without considering their lower operating costs.

Federal tax credits bring EV costs down even further. EVs are eligible for a tax credit of between $2,500 and $7,500, depending on battery size. In a number of cases, the tax credits provide enough of a boost to make the electric versions cheaper than their gas counterparts.

There are many calculators online to help you compare vehicle costs, but the Edmunds True Cost to Own calculator is the most comprehensive. The TCO takes into account depreciation, interest on financing, taxes and fees, insurance premiums, fuel, maintenance, repairs, and federal tax credits for alternative fuel vehicles. It also factors in geographic variations for actual sale prices, insurance, taxes and fees, and gas and electricity costs. It assumes the buyer has a good credit rating, drives the car 15,000 miles per year, and other average factors.

To generate the data for the graph shown above, I plugged a number of both gas and electric models into the calculator, using my own zip code in Berkeley, Calif.

I found that battery electric vehicles, like the Nissan LEAF, the Fiat 500e, and the Ford Focus Electric, not only do well in comparison to other vehicles, but they are in fact among the cheapest new cars on the road.

I started by comparing these three electric cars to their fossil twins — essentially the same car but with a gas-only engine.

The Nissan Versa Note has a sticker price $14,180, less than half of the LEAF’s price of $29,010. Yet the Note’s five-year cost came to $34,352, while the LEAF’s was $24,843.

This is also true for Ford and Fiat models, though they have less of a difference. The electric version of the Ford Focus has a sticker price of $29,170, about $10,000 higher than the gas version, but it costs about $5,000 less to operate over five years. The electric Fiat 500 has a sticker price of $31,800, a whopping $14,000 higher than the cheapest gas version (the Sport), but comes out nearly even over five years.

But how do the EVs compare with the cheapest gas cars, like the Nissan Versa sedan or the tiny Chevy Spark? The LEAF is still the hands-down winner, the cheapest car on the road over a five-year period.

Of course, your own total cost will depend on a dizzying number of variables. Driving habits matter: Since electrics cost less per mile, the more you drive, the more you save. Location matters too, as the cost of gasoline and electricity can vary dramatically in different parts of the country.

The TCO calculator tries to track real-world data, like the actual price paid for a car in a given area, rather than the manufacturer’s sticker price. Your results may vary.

Insurance also varies widely by driver and location. Even Aaron Lewis of Edmunds is stumped by how insurance rates are determined. “It’s as much a mystery to us as to the average consumer,” he says. “It seems like there is no rhyme or reason.”

Also, some states offer additional incentives (not calculated in Edmunds’ TCO database), which can bring the cost of an EV even lower. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 37 states and the District of Columbia offer incentives for EVs, including tax incentives, carpool lane exemptions, vehicle inspections or emissions test exemptions, free parking, or utility rate reductions. State EV rebates or tax credits range from $1,000 in Maryland to $6,000 in Colorado. Additional incentives are available for EV charging equipment.

California, as you might expect, has been particularly active in promoting EVs and other alternative vehicles, paying out $212 million in rebates for more than 100,000 vehicles since 2007, according to the Center for Sustainable Energy, which administers the program. Rebates vary by technology, with battery electric vehicles reaping a $2,500 reward. The program was recently reauthorized through 2023, with funds coming from the state’s carbon cap-and-trade program.

But other states are increasingly schizophrenic. As gas tax revenues decline, some are imposing new fees on electric vehicles to pay for road maintenance.

And some are cutting incentives. The Georgia legislature just repealed its generous state tax credit of up to $5,000 per vehicle, and imposed a special fee of $200 — more than a typical owner of a gas car would pay in gas taxes in a year, according to Green Car Reports. Atlanta, which has been an EV hotspot, is likely to cool down. Illinois recently suspended its $4,000 rebate, and a $2,500 incentive in Texas may expire soon.

Resale value is another wildcard. “My guess is that LEAFs are more popular so they’ll have much more value on the resale market compared to the Ford Focus EV,” says Lewis. It’s also possible that second-generation EVs with better batteries and longer range will make first-generation models obsolete.

Brett Williams, a senior project manager for the Center for Sustainable Energy, has been studying buying habits. “It’s a very complex calculation, which is why people are not fully understanding the savings they could be getting,” he says.

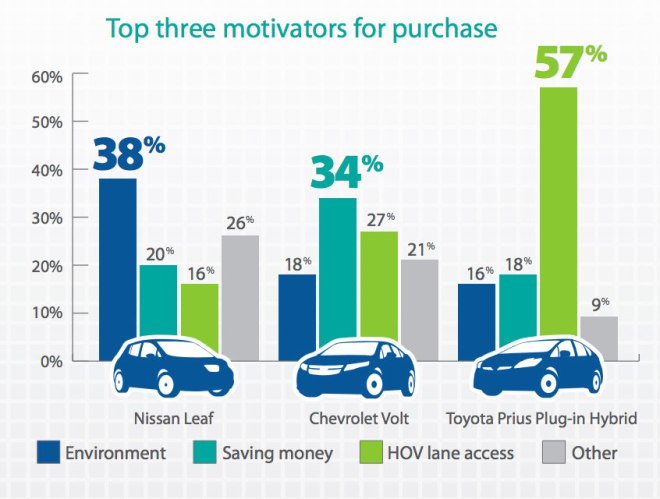

In 2014, CSE surveyed buyers of plug-in hybrid and battery electric vehicles in California. Overall, saving money was the No. 1 factor in their decision to buy an EV, cited as the “primary motivation” by 37 percent of those surveyed. This was especially true in the lower-income Central Valley.

Reducing environmental impacts was a strong second place statewide. The only group to rank environment over cost savings were battery electric vehicle drivers in the Northern Bay Area, like Marin County and the wine country of Napa and Sonoma.

The congested highways of the Bay Area and Los Angeles were the third factor for many drivers. California allows solo drivers in EVs to use carpool lanes during rush hour, saving precious time and aggravation.

Interestingly, motivation varied according to the model of car. “LEAF drivers claimed environment as the primary motivator,” CSE found. “Plug-in Prius owners indicate HOV lane access and Volt drivers said fuel savings.”

Nissan has tried different approaches to marketing the LEAF, according to spokesperson Brian Brockman. “We started with an environmental message, with polar bear ads, to resonate with early adopters,” he said. “More recently we are stressing the driving experience, like space and acceleration.”

Williams of CSE thinks the total cost of ownership could be a stronger selling point for car marketers and dealers. “It is an opportunity, given that 37 percent of our respondents picked cost savings as the primary motivation for buying their vehicle.”

CSE is studying ways to better communicate with buyers, such as by estimating monthly operating costs. “Research says that alone shifts people to buying a more fuel-efficient car,” says Williams.

More help for EV shoppers is on the way from a big data firm called Aculocity, which is developing a more sophisticated buying tool for the South Coast Air Quality Management District, the air pollution regulator for the Los Angeles region.

Aculocity developer Cornelius Kemp says, “EVs are likely to be cheaper, but it depends on your daily commute. That will really determine the cost of operating the vehicle. Different cars are best for different people, and that’s where we come in.”

So as long as your lifestyle can accommodate an electric car, you can enjoy saving money while you help save the planet.