Cross-posted from myurbanist.

Melbourne, Flinders Street Station, 1917Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Melbourne, Flinders Street Station, 1917Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

“100 years from now I wonder if those in the future who view these images will appreciate the value of … pictures as a means of recording life as is lived in this century … photography is in the truest sense biography — is it not the writing of life in a truly universal language?” — photographer Burton Holmes, Seoul, Korea, 1899

The Great Recession, climate change, and the quest for carbon neutrality have changed the way we look at cities, at the distance between home and work, and at the role of the automobile.

This change has given rise to a nostalgia for simpler times. We long for streets built on a more human scale, for a world of accessible neighborhoods now lost in the memories of previous generations.

Melbourne, Flinders Street Station, 2009, evolved as modern transit hub.Photo: (c) 2009 myurbanistPhotographs can restore such vanished urban memories, and recreate what political writer Alexander Cockburn has termed “the lost valleys of the imagination.” Innovative pioneers in documentary photography have left behind breathtaking records of the way people once lived. These images were taken at a time when most people hardly understood the camera, even as it recorded the profound change which surrounded them.

Melbourne, Flinders Street Station, 2009, evolved as modern transit hub.Photo: (c) 2009 myurbanistPhotographs can restore such vanished urban memories, and recreate what political writer Alexander Cockburn has termed “the lost valleys of the imagination.” Innovative pioneers in documentary photography have left behind breathtaking records of the way people once lived. These images were taken at a time when most people hardly understood the camera, even as it recorded the profound change which surrounded them.

One such pioneer was Burton Holmes, who worked with glass negatives, often hand-coloring the black-and-white images with single-hair ermine brushes. He also used motion pictures from the time of their invention.

He showed all that a city can be — while also depicting the changing form and appearance of infrastructure, public spaces, and the impact of this change on urban residents.

Holmes was not an intentional urban historian. He was a famous stage presenter, a showman who, from the late 19th century until the 1950s, presented “travelogues” to audiences, combining his photographs and motion pictures with lectures about the far-flung locations he visited. He brought the first motion picture cameras to the Far East, recorded Tolstoy and the coronation of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, and roamed the world — often visiting dangerous places where a camera had never been.

Travelogues, the Greatest Traveler of His Time, edited by Genoa Caldwell.His legendary travelogue narratives are well-chronicled in the work of Genoa Caldwell (The Man Who Traveled the World and Travelogues: The Greatest Traveler of His Time, recently republished as Early Travel Photography), as well as by other devotees, and can be readily reviewed in print and online (the most resource-intensive compilation is at burtonholmes.org).

Travelogues, the Greatest Traveler of His Time, edited by Genoa Caldwell.His legendary travelogue narratives are well-chronicled in the work of Genoa Caldwell (The Man Who Traveled the World and Travelogues: The Greatest Traveler of His Time, recently republished as Early Travel Photography), as well as by other devotees, and can be readily reviewed in print and online (the most resource-intensive compilation is at burtonholmes.org).

Caldwell, who has been researching Holmes’s work for over 30 years, has unearthed some insights into the way he viewed the urban landscape. His thoughts on Berlin, where he traveled in 1907, are one good example.

Holmes noted Berlin as a city of contrasts, where the traveler feels the unseen presence of something fine and beautiful. He described how the art of municipal housekeeping was practiced there to perfection: “Berlin is the best-kept great city in the world — there are no backyards in Berlin, [and] balconies filled with flowers ornament the buildings, [while] outdoor cafés give impressions of cheerful sociability, and the traveler is confirmed in his impression that Berlin is a city beautiful.”

Holmes also chronicled the impact of new forms of transportation as they were introduced into classical environments, and the resulting evolution of streets and ways of life. It is a priceless record.

BeIow is a sampling of the collection maintained by Burton Holmes Historical Collection (BHHC), reprinted with special permission and under copyright of BHHC. Caldwell has archived 1,700 of an assemblage which once numbered 30,000 photos, the rest lost to time. A range of movie footage, from 200 film cans rediscovered in 2003, now resides at George Eastman House in Rochester, N.Y.

A mode we have lost

A horse and buggy under Melbourne’s clouds. This is an urban scene lost to Western culture today. Holmes was fascinated by the expanse of the Australian continent and the impact of colonization on native people and place.

Melbourne, 1917.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Melbourne, 1917.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

A mode to regain

A grand Austrian urban stroll. Holmes reveled in the “superb edifice” of Vienna’s Grand Opera House, while his camera prioritized the pedestrian view.

Vienna, 1907.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Vienna, 1907.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Street scenes and carriage jams

Traffic congestion took different forms, often without protection from the elements. Consider the different social nature of traffic interactions without doors or windows, and the different sounds that filled the street.

Paris, 1895.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Paris, 1895.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

London, 1897.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

London, 1897.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

The ascent of the car

Early in the last century, Holmes toured Denmark by car. Here, a rare car-sighting south of Copenhagen in 1902. In contrast, by 1934 we see a predominant auto culture on Seattle’s Marion Street.

Copenhagen, 1902.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Copenhagen, 1902.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Seattle, 1934.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Seattle, 1934.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

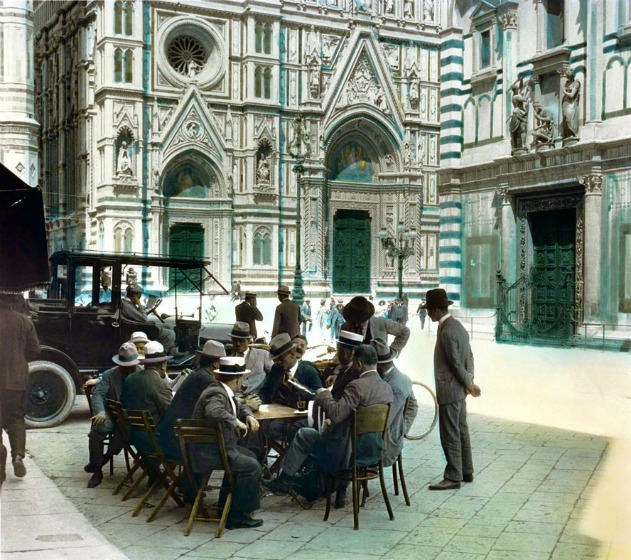

Gathering places

Note the human interaction in a public place as captured by Holmes in Italy and France, countries he repeatedly visited in times of war and peace. Today’s increasing attention to sidewalk cafés and public gathering spaces attempts to regain the ambiance of the photographs below.

Florence, 1924.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Florence, 1924.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Paris, 1918.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Paris, 1918.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

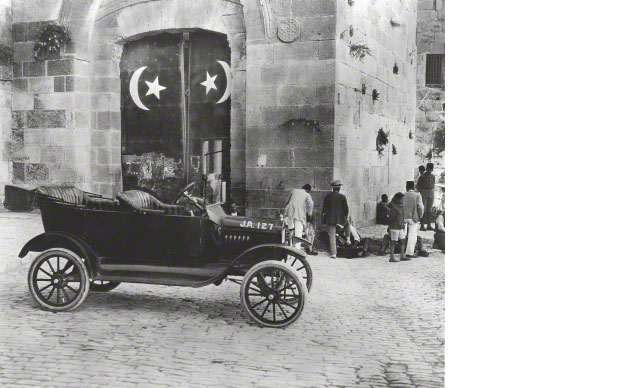

Change in the Holy Land

Jaffa Gate, in the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City, shows the evolution from animal to motorized transport at the sunset of the Ottoman Empire. The Jerusalem chronicled by Holmes is reminiscent of Mark Twain’s narrative in Innocents Abroad.

Jerusalem, 1920.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Jerusalem, 1920.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Jerusalem, 1920.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Jerusalem, 1920.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

A town with a purpose

The gold rush town of Dawson City, Yukon Territory was assembled in weeks. Holmes’ many photographs there documented a new town built on speculation with a surprising sense of permanence. Note the sidewalks.

Dawson City, 1903.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Dawson City, 1903.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

The romance of the bicycle

In Rome and Naples, Holmes captured the function and charm of the bicycle mingling with urban forms.

Rome, 1924.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Rome, 1924.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Naples, 1924.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Naples, 1924.Photo: (c) 2006 BHHC

Holmes’ work offers a central place to rediscover a classic model of urban life — a full experience shaped not just by where one could drive in a car, but by where one could walk or ride by animal, or access by public transportation.

The architect can derive the relation of building and street. The traffic engineer can see inspiration for lanes, surfacing, and signage. The lawyer and planner can react to setbacks, and ways to encourage pedestrian spaces while assuring light, air, acceptable noise levels, and governance of private use of public spaces.

Perhaps most of all, the child in all of us is transported by time-travel to a fantasy world better than the Emerald City of the Wizard of Oz — because the world in the photographs was real and foundational. In the end, the “film as biography” foretold by Holmes in 1899 draws us in, and challenges us to reclaim and relive the best of the city. It is a biography we should read as precedent, both for inspiration and for lessons learned from the consequences of change.