A city dog enjoys ice cream.

Cities run hotter than the countryside. There are a number of reasons why: the predominance of concrete, exhaust from cars, the angry people yelling at each other. And the problem, like every other heat-related problem in America, is getting worse.

From Brad Plumer at the Washington Post:

On a hot summer afternoon, a large city can easily run 5°F to 18°F hotter than surrounding rural areas, enough to turn an unpleasant heat wave into a deadly calamity.

And as global warming pushes up temperatures around the country, this urban heat island effect is only getting stronger. A new study in the journal Landscape and Research Planning finds that many large U.S. cities are warming twice as fast as the rest of the country. Between 1961 and 2010, rural areas in the United States heated up at a rate of roughly 0.29°F per decade. Yet three-quarters of the biggest U.S. metro areas were heating up at an average rate of 0.56°F per decade, thanks in part to increased sprawl.

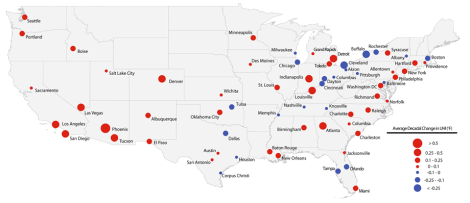

As part of their research, the team from Georgia Tech put together this map, showing how much the heat island effect had changed for various U.S. cities.

Click to embiggen. (Image courtesy of the Urban Climate Lab.)

Among the most affected, cities in the Southwest. Cities in the Northeast, particularly along the Great Lakes, saw some reductions. (It would be interesting to see this data correlated with economic activity.)

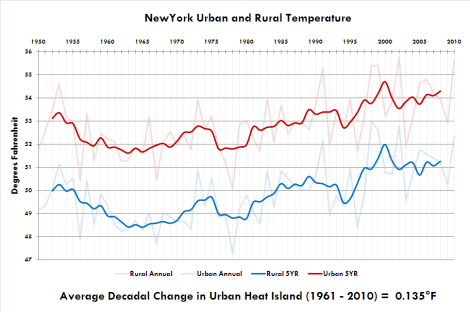

Here’s what the data for New York City and nearby rural areas looks like.

It’s clear that, over time, temperatures in the city and in the surrounding area are moving higher together. Of course, the “rural” areas near New York City are not terribly rural.

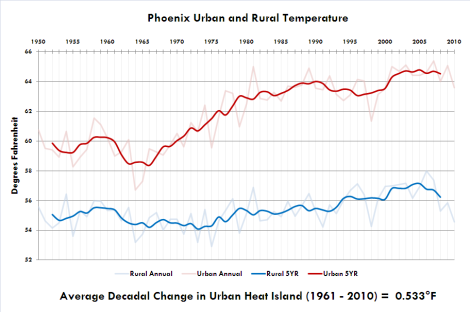

Compare that with Phoenix.

Here, you can see a widening gap between the city and its surroundings.

Plumer notes some steps cities can take.

More plants can cool a town down — both New York City and Los Angeles are trying to plant one million trees, for instance. Cities can also try to use more reflective material for their roofs and pavements, in order to reflect more sunlight rather than absorbing it. (Rooftop solar panels could help, as well.) Improved energy efficiency could reduce the amount of waste heat from buildings and factories. On average, [Georgia Tech’s Brian] Stone says, an aggressive strategy could cut the urban heat island effect in half, shaving 5°F to 7°F off temperatures on a hot summer afternoon for a large city.

Excessive heat is brutal, unpleasant, and deadly. The death toll from this summer’s heat waves in the U.S. already tops 100; in 2003, a heat wave in Europe was blamed for over 71,000 premature deaths.

Used to be, many New Yorkers got out of town for the weekend, escaping into the cooler temperatures in their rural surroundings. That’s not really practical for most people any more. So we ought to do our best to bring the cooler temperatures into the city.