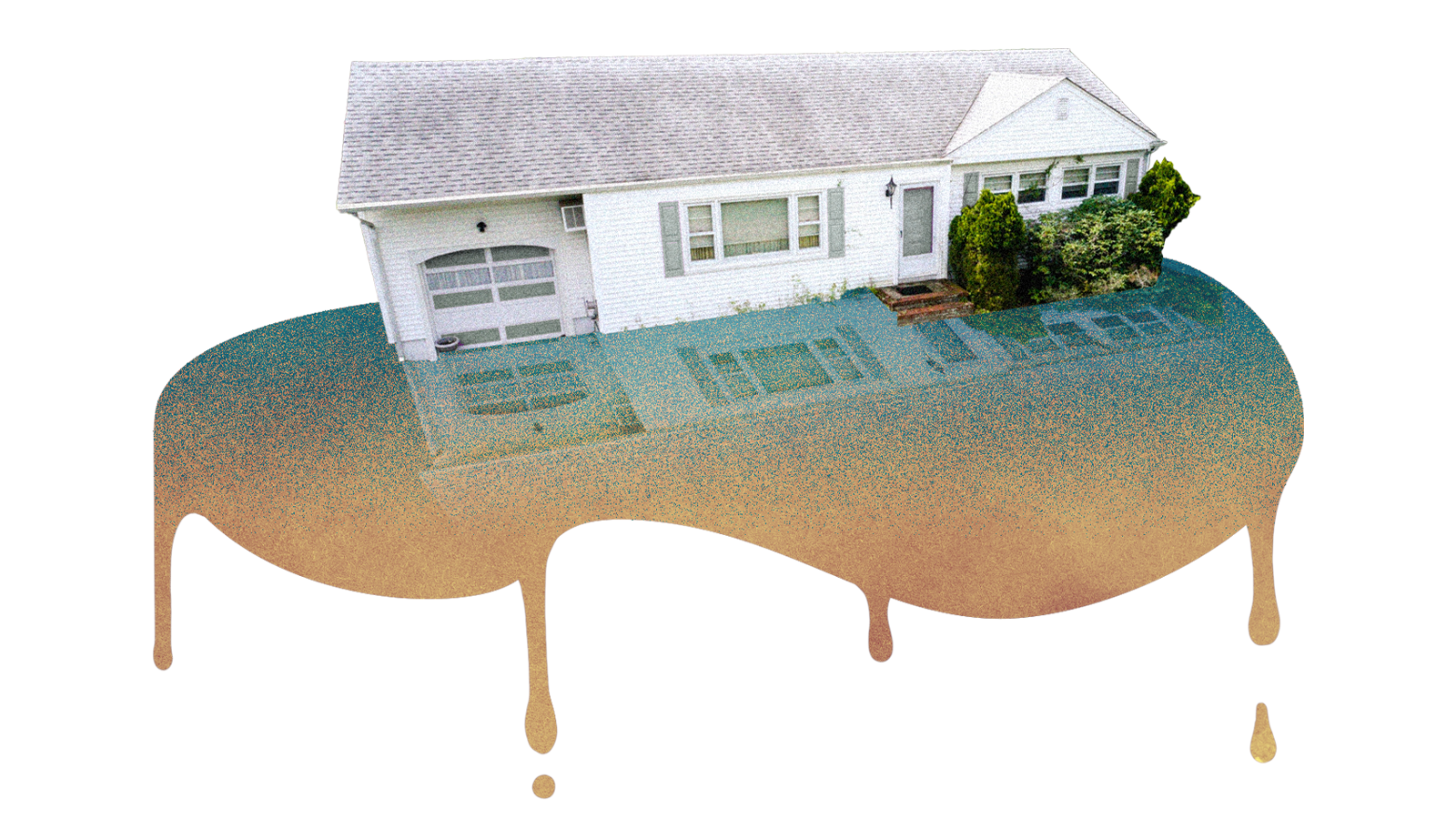

For 30 years, residents of Centreville, Illinois, have been forced to live with pools of their own feces. Nearly every time it rains in the town, where 96 percent of the residents are Black, raw sewage bubbles up from the ground like a crappier version of the oil-spewing scene from the Beverly Hillbillies. When the streets flood, as they do multiple times a year, neighbors have to take out boats to navigate poop-filled waters. Afterward, soggy toilet paper bits hang from shrubs like Christmas lights.

It’s not like residents haven’t tried to get the problem fixed. Earlie Fuse has lived in Centreville for 29 years. In that time, the 80-year-old says he has spent thousands of dollars to protect his family from the encroaching waste, replacing multiple walls that have collapsed under the weight of water damage. His basement, once a place for entertaining guests, is now an uninhabitable mud den. As a member of Centreville Citizens for Change, a group of residents demanding solutions to the flooding in the area, he and fellow resident Cornelius Bennett filed a lawsuit against the city government of Centreville. The lawsuit alleges that the city is legally required to fix and maintain the local water and sewage system, but has deliberately ignored the flooding for years.

“[Centreville] needs help,” he says to anyone who will listen, from elected officials to the dozens of attendees at a recent panel titled, “Flooded and Forgotten.”

The reasons for Centreville’s sewage woes are no secret. The city sits in a low-lying area, and even short rains can cause flash flooding, sometimes as high as 2 feet. The deluge overwhelms the area’s septic system, creating puddles contaminated with you-know-what that can persist for weeks. The area has pump stations designed to guide sewage away from local streets and homes, but these date back to World War II. Now, they are barely functional, allowing human waste to infiltrate homes and streets.

Photos courtesy of Equity Legal Services

Corruption is an ongoing theme behind the pump system’s neglect. In 1976, Commonfields of Cahokia, a public utility company, bought Centreville’s sewage system. The company has since been at the center of several major investigations, leading to at least two employees in leadership positions being convicted of federal financial crimes. In a 2012 federal court case, then-Commonfields General Manager, Dennis Traiteur Sr., testified that “everyone” at Commonfields, which still manages the city’s tap and wastewater, was “hired for political reasons.” That dynamic, he said, contributed to the neglect of Centreville’s septic situation.

Residents say the area’s sewage problems got worse after the construction of a local interstate highway, which cuts directly through the city. Studies have shown that highway placement is a form of redlining — systemic disinvestment that results in lower property values and fewer resources in many neighborhoods of color. Following the highway’s completion in 1986, pump stations meant to move sewage away from homes began to regularly malfunction. Years later, the Army Corps of Engineers declared that the highway had impeded the flow of water from Centreville to the drainage canal designed to collect surface water.

Beyond the financial pain Centreville’s sewage problems have caused residents, the flooding has taken a toll on locals’ mental and physical health. People who live in the area are exposed to heightened levels of bacteria and mold. They are more likely to suffer from illnesses, such as hookworm and typhoid, that have been largely eradicated in other parts of the U.S. Centreville doctors have speculated the area’s water may even be linked to heart attacks.

Reports have shown that the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency has been aware of the area’s regular flooding since at least 2003. In 2009, it acknowledged that the ditch that drains the floodplain in Centreville contained hazardous levels of fecal coliform bacteria.

But despite the abundance of information, local leaders failed to act. In 1989, the Environmental Protection Agency awarded a grant to the nearby town of East St. Louis, which shares the same water system as Centreville, to repair the defunct sewage system. But rather than fix the overwhelmed drains, East St. Louis officials misappropriated the funds, diverting it to its general fund to help alleviate its $35 million debt. That was a low blow for Centreville, regarded by many accounts as the poorest city in America.

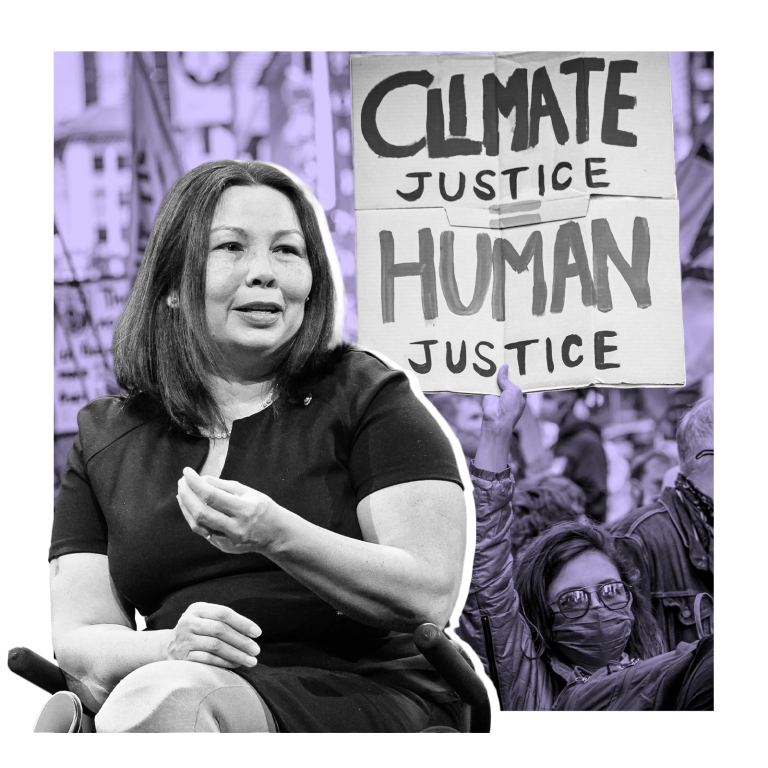

If that funding is awarded to Cahokia Heights — aka the soon-to-be-merged communities of Centreville, Alorton, and Cahokia — the money could help repair and replace the area’s overflowing sewer systems. Determined not to let another opportunity to fix Centreville’s poop problem slip away, state politicians, including Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker and U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth, are lobbying hard for the FEMA funds to go to the new community. (FEMA, which has set aside $500 million for the program, will name the awardees this summer.)

Residents’ reaction to the political outpouring has been mixed. Lyles, for example, proudly welcomes the support of both Pritzker and Duckworth, but she is still hesitant about promises made by local leadership. Recently she was visited by Centreville Supervisor Curtis McCall Sr., who is slated to become mayor of the merged Cahokia Heights.

“I hope that McCall will do what he’s supposed to do, but he has also been in a leadership role this whole time,” Lyles said. “We can talk about this until we’re black and blue, but to know that you didn’t care enough to come out and check on us when you knew all of this was going on says it all.”

“This is a multifaceted, oppressive form of racism,” she added.

Even if the community gets the FEMA money to update its infrastructure, more should be done to ensure history doesn’t repeat itself, said Nicole Nelson, director of the legal advocacy organization Equity Legal Services. She helped Centreville resident Earlie Fuse bring the lawsuit against the city last year. She said Centreville residents are concerned by the possibility of grant funds being mismanaged once again by local officials — especially as homeowners would not be able to apply for the money directly to fix their flood-damaged homes. Centreville’s grant application only solicited support for the repair and maintenance of sewage systems in the area.

“There’s no denying that Centreville residents need money coming into the community,” Nelson said. “I think the problem is that even if these systems are fixed, the residents are still left with homes that have been devastated by these systems for decades.”