At the end of July 2023, 3.07 inches of rain fell on Boston in a single day. The city’s sewer systems were overwhelmed, resulting in a discharge of sewage into Boston Harbor that prompted a public health warning. The summer of 2023 would turn out to be Boston’s second-rainiest on record.

About two months later, 8.65 inches of rain fell on New York City — higher than any September day since Hurricane Donna in 1960. The city’s low-lying areas were deluged, and half of its subway lines were suspended as water inundated underground stations.

East Coast cities are increasingly susceptible to flooding due to climate change. But changing weather patterns are only half of the problem — the other is inadequate infrastructure. In particular, these recent flood events were made worse by Boston and New York’s combined sewer systems, which carry both stormwater and sewage in the same pipes. When such a system reaches capacity during heavy rainfall or storm surge events, it backs up, sending a mixture of stormwater and raw sewage into waterways (and sometimes also into streets and homes).

Many other cities around the country also have combined sewer systems, but as two of the oldest, densest major cities in America, Boston and New York face an uphill battle when it comes to climate-proofing their sewer systems. And the cities have chosen two very different paths: Boston has elected to separate the combined portion of its sewer system so that sewage no longer mixes with stormwater during flooding events, while New York is betting on new, detached rain management infrastructure to relieve the burden on its combined sewers when it rains.

The success of their respective solutions isn’t just a matter of reducing flooding hazards for city residents and surrounding ecosystems — it’s also required by law. That’s because flooding-related backups that send sewage into waterways, known as combined system overflows, are a violation of the Clean Water Act. In response to combined system overflows, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has entered into consent decrees with Boston and New York City’s municipal governments — legally binding agreements under which the cities must prevent further overflows. John Sullivan, the chief engineer at the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, estimates that 90 percent of sewer systems in the country are under a consent decree.

A consent decree “outlines how many years you have to get this problem fixed,” said Sullivan, “and they give you plenty of time, but you’ve got to take actions to meet the things you weren’t meeting.”

Boston is currently in dire need of better flood management infrastructure. Sea level rise occurs disproportionately faster on America’s East Coast, due to factors including wind patterns and a changing Gulf Stream. Meanwhile, climate change is also increasing the amount of moisture in the atmosphere, making heavy precipitation more likely. The double whammy of rising sea levels and intensifying heavy rainfall events worsens the impact of surge flooding during storms. In Boston specifically, high-tide flooding is increasing more than three times faster than the national average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Such flooding can swallow up outfalls, the pipes that send excess sewage into waterways when the system is inundated, further reducing the rate at which water drains out of cities.

Boston has actually been working on separating its sewer system since before climate-related flooding became a major threat. In response to a 1987 court order, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority undertook nine sewer separation projects in the Boston area between 2000 and 2015, along with dozens of other sewer improvements intended to prevent combined system overflows. Today, only about 10 percent of the Boston Water and Sewer Commission’s 1,538 miles of sewer pipes are combined.

Currently, the commission is working on two additional sewer separation projects in South and East Boston. The city is prioritizing the prevention of overflows in areas where the risk of human contact with contaminated water is deemed the highest, like at public beaches.

These projects are costly. According to the sewer commission’s calculations, the city’s sewer separation works in 2021 cost an average of $340,000 per acre. Around 88 acres of work were done that year — translating into a price tag of more than $30 million. From 2024 to 2029, the city plans to separate sewers in 230 acres in East Boston and 400 acres in South Boston. These planned works make up about 3 percent of Boston’s sewer system, which comprises approximately 20,500 acres, including portions that have always been separate.

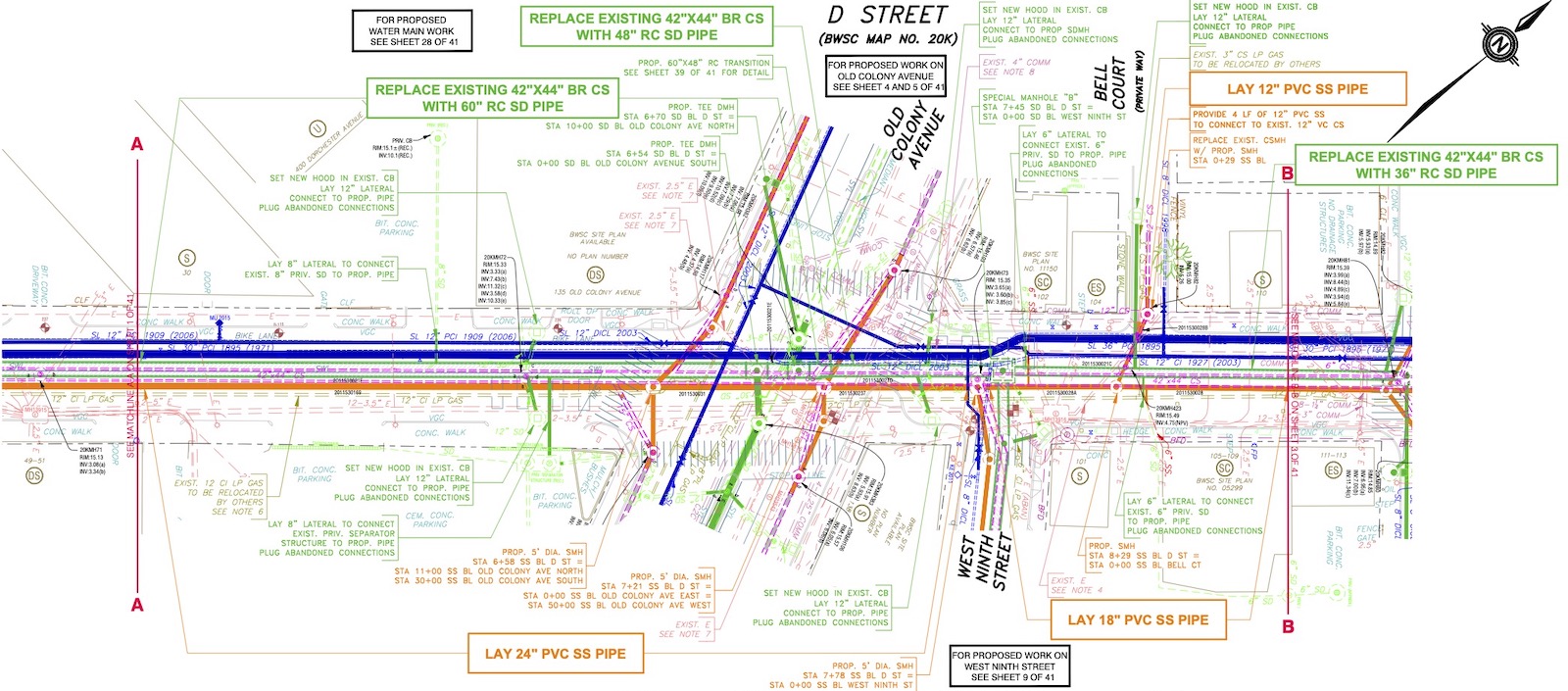

Another problem is finding sufficient space for the addition of new pipes — a luxury in some areas in the city. Sullivan sent Grist a blueprint of plans for sewer separation works in South Boston. It contains a flurry of lines of varying thickness and color, some solid and others dotted, stacked atop each other. Each represents a different underground pipe.

“You can see how messy they can be, trying to fit these pipes under the gas pipes, under the electric, under the telephone,” said Sullivan.

Sewer replacement — most of which takes place deep underground — also presents safety concerns for workers, such as low oxygen levels, the inhalation of resin fiberglass vapors, and the presence of foreign objects in sewers. The contractors overseeing the work install oxygen meters in tunnels that sound when oxygen levels dip to a dangerous low.

According to Sullivan, the risks of sewer replacement are worth it in the face of intensifying precipitation.

Though he says that 90 percent of Boston’s storms do not exceed 1 inch of precipitation, and can be mitigated by existing flooding infrastructure, at times they can dump up to 6 inches of rainwater on the city.

“You need the infrastructure to move that 5 inches of water out,” said Sullivan. “And that isn’t done by any green infrastructure, that is pipes.”

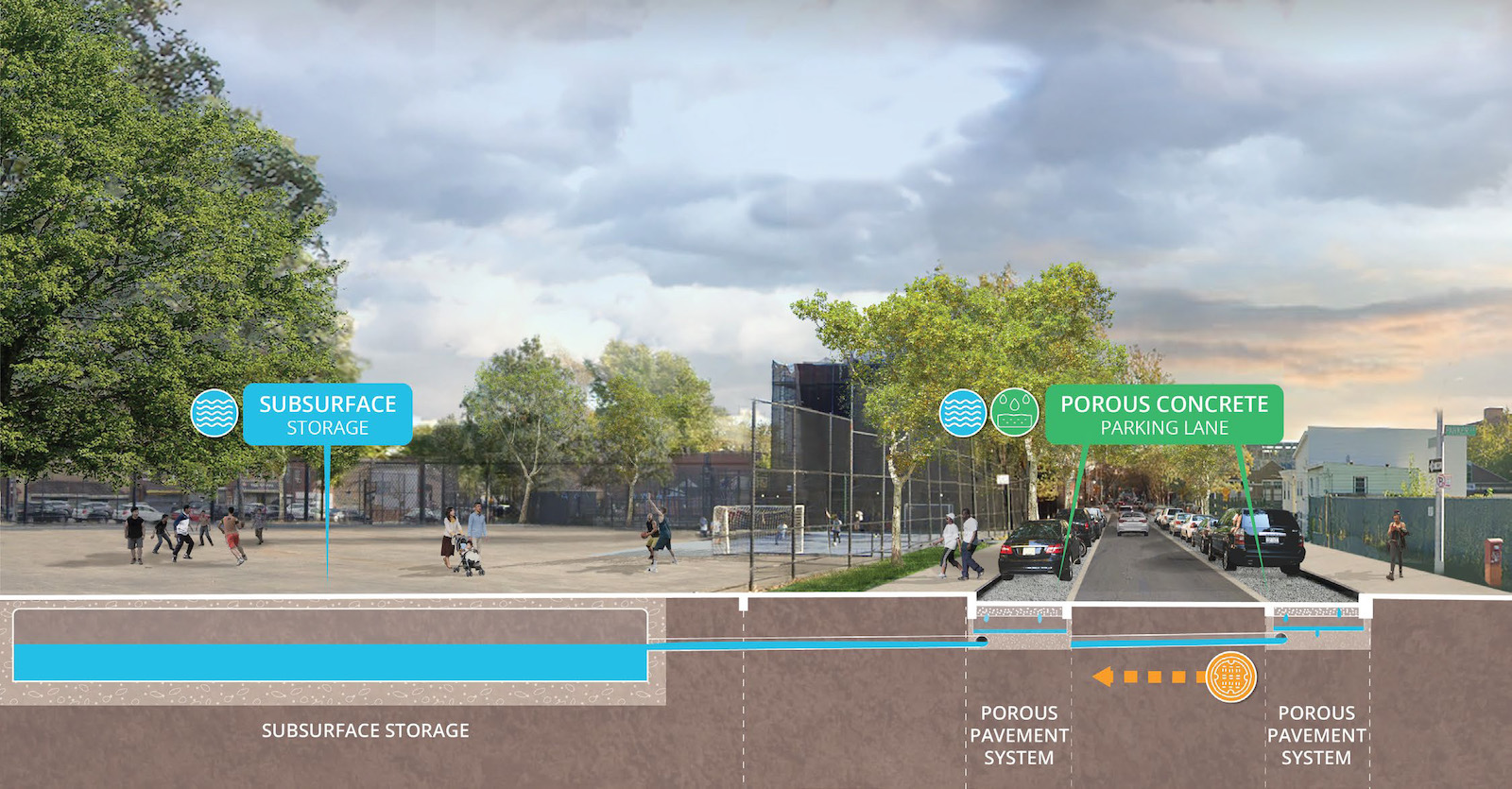

New York City, however, is betting that green infrastructure will do the trick. About 60 percent of the Big Apple’s 7,400 miles of sewer lines are combined, and the city has estimated that fully modernizing the system would cost around $100 billion and take decades. The New York City Department of Environmental Protection’s alternative to separating significant portions of its combined sewers is the Cloudburst plan, developed in partnership with the city of Copenhagen, Denmark, starting in 2017. The plan utilizes newly built gray infrastructure like underground storage tanks, and green infrastructure such as rain gardens, to divert stormwater during heavy downpours. A rendering of Cloudburst infrastructure on the Department of Environmental Protection’s website illustrates how porous concrete in parking lanes could capture stormwater runoff and funnel it into underground tanks for temporary storage.

In early 2023, the city unveiled plans for $84 million worth of Cloudburst infrastructure at eight public housing developments, including sunken basketball courts that can capture stormwater in the event of heavy rain. It also announced additional, larger Cloudburst initiatives funded by $390 million in capital funds in four focus neighborhoods in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens. These areas were chosen based on several factors: history of flooding, future inundation risk via modeled stormwater flood maps, and socio-economic vulnerability.

Alexx Caceres is a native of East New York, one of the four focus neighborhoods, and works as the farm manager of East New York Farms. Caceres says they welcome the planned infrastructure. During the storm last September, the front of Caceres’ farm was inundated. They hope that the Cloudburst infrastructure will help to prevent subsequent sewer overflows and floods.

“They are trying to create infrastructure that holds the water in,” Caceres said, “giving the sewage system time.”

Other peripheral Cloudburst initiatives in Staten Island and the Bronx have sought to restore natural drainage corridors that have been built over by urban developments.

While effective in creating more pathways for stormwater to flow out of the city, these projects may be less feasible in more population-dense boroughs such as Manhattan, according to Daniel Zarrilli, the chief climate and sustainability officer at Columbia University.

The New York City Department of Environmental Protection declined to comment on its plans to manage flooding.

Across America, other cities are facing the same choices as Boston and New York — often with less money available to them. States and localities are responsible for more than 90 percent of America’s public water infrastructure spending each year. According to Joseph Kane, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, a think tank specializing in economic and policy research, this means that cities bear most of the financial burden of addressing outdated sewer systems.

“I don’t think communities often want to reach the point of a consent decree,” said Kane, but “the systems are old, and in many cases the utilities have not had the financial capacity themselves to proactively stay ahead of these repairs.”

An EPA grant program that originated in 2018 amendments to the Clean Water Act provides small grants for cities to work on their sewer systems. The 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law brought about another infusion of federal resources, mainly in the form of the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, which funneled $11.7 billion in loans to states, which in turn distributed them to individual utilities. Kane said, however, that this legislation only slightly alleviates the economic burden for states and utilities, which ultimately have to repay these loans.

“It’s still just a blip compared to the magnitude of the cost that states and localities themselves are having to bear,” said Kane, on existing federal resources for flood management.

The funding from the bipartisan infrastructure law is also slated to last through 2026.

“There are already questions in Washington and across the country that when this funding lapses in another couple years, is there going to be additional support for these sorts of projects?” said Kane.

Several American cities have turned to the imposition of stormwater fees to raise funds for sewer system improvement work. The fees are paid by individual property owners, shifting the costs of flooding prevention onto the community. Stormwater charges are calculated based on the impervious surface cover of the property — those with a higher area of impenetrable surfaces, such as rooftops and parking lots, are charged a higher amount.

In April, the Boston Water and Sewer Commission implemented a stormwater charge that applies to all properties with over 400 square feet of impervious area. New York City has yet to implement any stormwater charges.

“Stormwater fees create a connection for property owners to chip in something for their contribution to the stormwater runoff challenges,” said Kane, “but there’s a lot of debate on exactly how high these stormwater fees should be, how they’re calculated, who pays what.”