Almost every time it rains in New York City, the grounds of the South Jamaica Houses start to flood. As the storm drain system overflows, water collects across the sprawling public housing development in southeast Queens. Before long, floodwater pools up on the basketball court and in the yard behind the senior center. If it rains for more than a few hours, the water starts to slosh over streets and courtyards. These aren’t the monumental floods that make national headlines, but they make basic mobility a challenge for the complex’s roughly 3,000 residents. Sometimes the water doesn’t drain for days or weeks.

“It happens all the time,” said William Biggs, 66, who has lived in the development for 35 years. He gestured at the basketball court, which is cracked and eroded in places. “It pools all the way through the court, all the way back toward the buildings, all along that wall there. And the reason is that we don’t have any drainage. The storm drains don’t work.”

“If you put some fish in there, you could go fishing,” added Biggs’ friend Tommy Foddrell, who has lived in the development for around two decades.

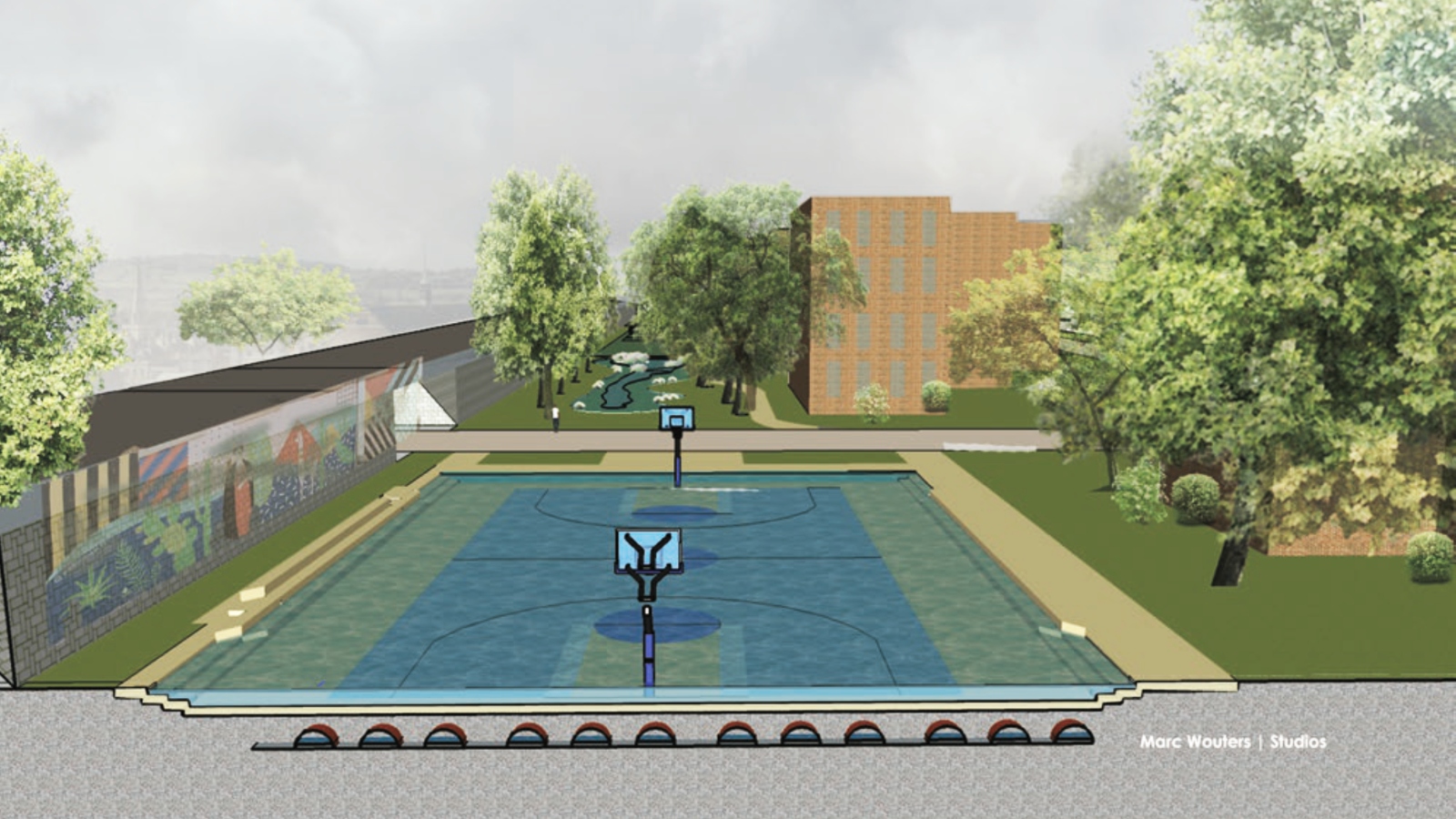

That decrepit basketball court will soon become a centerpiece of New York City’s efforts to adapt to the severe rainfall caused by climate change. In the years to come, construction crews will sink the court several feet lower into the ground and add tiers of benches on either side. During major rainstorms, the sunken stadium will act as an impromptu reservoir for water that would otherwise flood the development.

The project will be able to hold 200,000 gallons of water before it overflows, and it will release that water into the sewer system slowly through a series of underground pipes, preventing the system from backing up as it does today. Just down the block, work crews will carve out another seating area arranged around a central flower garden. That project will hold an additional 100,000 gallons of water.

In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, which struck New York City 10 years ago this month, the city spent billions of dollars to strengthen its coastline against future hurricanes. Sandy had slammed into the city’s southern shoreline with 14 feet of storm surge, inundating coastal neighborhoods in Queens and Staten Island. The city’s biggest climate adaptation goal in the years that followed was to make sure that these coastal neighborhoods were prepared for the next storm surge event.

But the next Sandy turned out to be a very different kind of storm. In September of last year, the remnants of Hurricane Ida dumped almost 10 inches of rain on New York City, including three inches in a single hour. Rather than indundating the city’s shoreline, the storm dumped heaps of rain on inland neighborhoods, overwhelming neighborhood sewer systems and filling up streets with water. The flooding killed 13 people, most of whom lived in below-ground apartments that didn’t typically see flooding.

Now the city is trying to retool its climate plans to be prepared for the intensified rainfall of the future. This time, the New York City Housing Authority, or NYCHA, is at the heart of the effort. The South Jamaica Houses project is the first in a series of initiatives that will turn NYCHA developments into giant sponges, using the unique architecture of public housing to capture rainfall from so-called “cloudburst” events and prevent floods like those caused by Ida. Three of these projects are already in the works in three different boroughs, supported by a hodgepodge of federal money.

Adapting for cloudburst events is very different from adapting for storm surge. While the latter requires building large new infrastructure projects along the coastline, preparing for inland events like the former requires squeezing new water storage infrastructure into an already-crowded street grid.

“There’s already a system to deal with stormwater in these neighborhoods — there’s a big stormwater sewer under the street,” said Marc Wouters, an architect whose firm helped design the South Jamaica Houses flood project. “But those are undersized for these bigger rain events that are coming.”

Even before Hurricane Ida, city officials had long been aware that cloudburst events could cause flooding even in landlocked neighborhoods. There just wasn’t much money to address that threat. The federal disaster relief system allocates most adaptation money to communities that have already suffered disasters, not communities trying to prepare for disasters that haven’t happened yet.

That meant that the vast majority of the money the city received after Superstorm Sandy went to protection against coastal storm surge: The city rebuilt massive sections of the Rockaway and Coney Island beaches, bought out whole neighborhoods on Staten Island, and charted an ambitious plan to surround Lower Manhattan with an artificial shoreline. That kind of money wasn’t available to protect against hypothetical cloudburst disasters.

But there was one city department that had already started to plan for stormwater flooding. A few years before Hurricane Ida, NYCHA had hired Wouters’s firm to hold a design workshop at South Jamaica Houses, interviewing residents about their flood problems. Those conversations led to the basketball court design, the city’s first major attempt to retrofit a public housing project for cloudburst flooding. It’s a strength of the project that it also promised to fix the dilapidated court: maintenance of the city’s public housing stock, which is home to well over 300,000 New Yorkers in all five boroughs, is notoriously behind schedule. Bundling long-desired repairs with climate adaptation promised to be a win-win.

“If you sink the basketball court into the ground and have it as a temporary collection pond, then it would justify rebuilding the basketball court,” said Wouters.

The South Jamaica project was cheap enough that the city’s Department of Environmental Protection could execute it without a big federal grant, but NYCHA officials wanted to take the South Jamaica houses model to other housing projects. The authority’s climate adaptation study identified dozens of developments that were at high risk of stormwater flooding, but it didn’t have the money to replicate the South Jamaica project. Like most public housing authorities across the country, NYCHA often struggles to find the money for even basic capital repairs, thanks to a long decline in federal funding over several decades. Most of New York City’s climate adaptation money, meanwhile, was flowing toward coastal protection projects.

Luckily, the flooding from Hurricane Ida coincided with a rush of new federal spending on climate resilience. In the waning days of the Trump administration, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, launched a new resilience grant program. The bipartisan infrastructure bill signed by President Biden last year expanded that program as well as an existing disaster mitigation fund. The first tranche of this new funding became available just as New York City was reeling from Ida, and the city quickly grabbed two more grants to replicate the South Jamaica concept at a pair of public housing developments in Brooklyn and Manhattan. The two grants together total around $30 million. That won’t make a dent in the authority’s broader adaptation needs, but it’s a start.

During severe rainfall events, the city’s ordinary storm drain system fills up, and all the extra water starts to pool in the lowest-lying areas. The task for designers like Wouters is to find a place to store excess water, whether above or below ground, before it filters into the storm drain system.

This looks a little different in every development. At Harlem’s Clinton Houses, one of two projects where the city has secured a grant from FEMA, officials will have ample room to carve out a large “water square” like the one at the South Jamaica basketball court, as well as install underground basins where water can accumulate. These basins will be able to hold a combined 1.78 million gallons of water, slowly releasing it out into the sewer system so it doesn’t spill onto nearby streets. The project at the Breukelen Houses in Brooklyn may not feature as much underground storage isn’t an option: Because the housing complex is so close to the ocean, its water table sits just a few feet below street level, making it harder to excavate new storage tanks. Designers will instead have to create natural water sinks above ground, perhaps by lining streets and walkways with thirsty grasses that trap water in their roots, making the whole development one big sponge.

These strategies are enabled by the fact that the average New York public housing project looks very different from a typical city neighborhood. Instead of mid-rise buildings on a grid of intersecting streets, a development like Clinton Houses consists of much taller towers arranged around central courtyards and walkways. There are no streets that allow cars to pass through, and the footprint of each building tends to be smaller.

This unique architecture is a blessing when it comes to flood resilience. Most NYCHA developments contain ample open space for water storage projects like the South Jamaica basketball court, allowing officials to look beyond the usual underground pipes and tanks. In addition to solving flood problems for NYCHA residents, these fixes can also help surrounding neighborhoods by catching water before it flows out onto other streets, reducing the total burden on a neighborhood’s storm drain system. In other neighborhoods, the city will have to settle for smaller-scale interventions like sidewalk rain gardens.

“NYCHA developments interrupt the street grid and create large amounts of green space within a dense urban environment, [and] are clustered in parts of the city where green space resources other than NYCHA developments are limited,” a representative from the authority told Grist. “For this reason, NYCHA’s campuses provide an opportunity for management of larger volumes of water than would be possible within the typical street grid configuration in the city.”

Still, there is a bitter irony in the post-Ida funding surge at NYCHA. The new federal money may help solve flooding issues at the developments that are lucky enough to get it, but it won’t solve the numerous other infrastructure issues that have plagued the developments. The authority has spent the past several years embroiled in a scandal over its attempts to conceal missed lead paint inspections, and the federal monitor assigned to supervise the authority has concluded that some 9,000 children are at risk of dangerous lead paint exposure. Dozens of boilers have also failed at agency projects in recent years, leaving thousands of residents to brave winter temperatures with no heating.

At South Jamaica Houses, stormwater flooding is far from the only issue. The development’s wastewater system is also prone to failure, and in 2015 it backed up and flooded the inside of buildings with fecal matter and sludge. Residents of the Clinton Houses, meanwhile, have suffered through outbreaks of toxic mold in recent years. Breukelen Houses residents have been pleading with the city to take action on gun violence that has claimed several lives in the development.

The authority’s extensive repair backlog is in part the result of a decrease in federal funding over the past several decades, but NYCHA officials have also made serious and wasteful mistakes, like working with shoddy contractors. The flood project in South Jamaica Houses might mitigate this shortfall by killing two birds with one stone, but it wouldn’t need to do so if NYCHA had been able to fix the basketball court in the first place.

“I don’t know if [grant money] is the only way to make those improvements, but it certainly is incredibly helpful,” said Wouters of the secondary benefits at a project like South Jamaica Houses. “And I think it becomes really an efficient use of federal dollars, because you’re spending each of those dollars to do multiple things.”

NYCHA’s new generation of flood projects will prepare some of its developments for an era of more intense rainfall, but they’ll only address one of many challenges that public housing residents face. In other words, there’s more than one kind of resilience, and NYCHA is far from equipped to tackle all of them.

Biggs, for his part, isn’t yet optimistic about the flood resilience project near his home at the South Jamaica Houses. He rattled off the a litany of the development’s other maintenance problems, like the doors that don’t lock and allow people who don’t live in the complex to wander in and out at will.

“Thirty-five years I’ve been here, and I’ve never heard of anything changing,” he said. He recalled the conversations around the basketball court plan, but he doesn’t think they will lead to anything tangible. “They always do a good dress-up, but they haven’t fixed shit yet.”