If you live in a community plagued by violence, poverty, and health problems, it can be hard to see our collective ecological crisis as more pressing than the everyday crisis of survival. That’s the problem artist Marc Bamuthi Joseph, founder of the national Youth Speaks poetry program, set out to tackle with his Life is Living festivals, which he describes as an effort to “green the ghetto” by asking first, “What sustains life in your community?” The festivals have been held in Chicago, New York, and Houston, and happen every year in Oakland, where Joseph lives. They bring together artists, philanthropists, environmentalists, community organizers, social service organizations — “folks who share values but have different modalities — around this one value, which is life.”

Joseph created a work of performance art based on the Life is Living festivals called red, black, and GREEN: a blues that’ll be performed in different cities over the next year. Incorporating song, dance, spoken word, monologue, and multimedia visuals, the piece tells the stories of people Joseph met who fight every day to sustain life around them — a Chicago mother coping with the loss of her son to gang violence, folks cultivating a garden built on an old junkyard in Houston’s Fifth Ward, Joseph’s own struggle to explain the Black Panthers’ legacy to his young son. The heavy material is buoyed by moments of humor, like the depiction of hard-core enviros’ holier-than-thou approach to green living (“Are you eatin’ local, organic, non-packaged, and fresh? Are you a vegan, eatin’ in season, freezin’ what’s left?”) that made a diverse Seattle audience laugh in recognition.

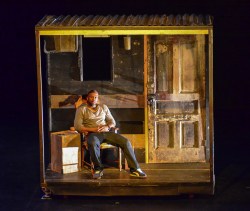

Marc Bamuthi Joseph (center) at the Life is Living festival in Chicago. (Photo by Bethanie Hines.)

The show doesn’t offer an easy answer to the question of how to transform the environmental movement into a universally inclusive one. Instead, it interprets the movement from the perspective of communities where sustaining life is about a lot more than changing light bulbs — a perspective too often missing from mainstream conversations about sustainability.

I talked to Joseph before I saw the show.

Q. What led you to produce Life is Living?

A. The primary pathway was through my work with young writers at Youth Speaks. We were able to partner with Robert Redford and the Sundance Institute about five years ago to engage young writers in the area of climate change. Our programming was really successful, but the primary audience was high-end luminaries, powerful and engaged and already environmentally literate crews of people. It seemed like there was a need to have a multi-channeled approach to environmental literacy, starting with how we engage with black and brown and under-resourced communities.

Q. How do the festivals achieve that engagement?

A. The core work behind Life is Living is to rebrand the idea of environmental consciousness, so that rather than using the word “green” as a primary codifier, we use life as the primary value. The central question is “What sustains life in your community?” And the festival is the performed response to that question. Sustainable survival practices [are] already present in black and brown communities; we just shed a light on them in a way that amped up their accessibility inside the community.

The environment looks like us, you know what I mean? It doesn’t look like a polar bear or a rainforest. Those are critical things, too, but what the festivals show is, we are what we’ve been waiting for. If we conceive of our everyday activities as being part of an interdependent network, then that’s the first step toward preserving life and the health of the planet.

Q. What kind of transformation do you hope to inspire in audiences?

A. I think we’re a great people. I really believe in our humanity. And I also believe we can get better. You don’t have to see the piece and eat local, organic, non-packaged, and fresh; you don’t have to turn into a vegan, eatin’ in season, freezin’ what’s left. It’s more emotional. I’d like to see in all of us a greater sensitivity and belief in what’s possible. If there’s a greater sense of hope, and then perhaps a call to action, I’d say the work is being done.

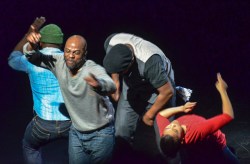

A scene from red, black, and GREEN: a blues. (Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.)

Q. Can you talk more about how to bridge the gap between the ecological crisis and the everyday crises faced by black, brown, and under-resourced communities?

A. Whole Foods or the Prius: Those are the ways that we’ve branded the [environmental] movement. Part of what Life is Living seeks to do is rebrand these ideas so they’re more reflective of the world we live in.

There’s also the ugly truth that in the communities we’re working with, we have high homicide rates, HIV rates, children born with birth defects, women with cancer — we’re defined by our pathologies. It would be irresponsible and incongruent to talk about green space if I wasn’t talking about the death of black boys. In the show we say, “If you brown, you can’t go green until you hold a respect for black life.” Kids are being murdered every day in Chicago. When kids feel like it’s OK to practice murder, the first thing we have to do is have a greater appreciation of life.

Q. What gives you a sense of hope?

A. We as a planet have undergone an industrial revolution, and that revolution improved the quality of life for human beings. That same ingenuity, that same innovation, hasn’t left. It’s been totally consumed by corporate culture and infatuation with money. Maybe I am naïve, but I believe that at the end of the day, our humanity will win out. I feel the same way about race, I feel the same way about gender and sexuality — we eventually orient ourselves to the moral good. That’s what history teaches us: The moral arc bends toward justice. I think the global arc will bend toward environmental justice. Because the planet is going to be here whether we like it or not. It will purge itself of us if we don’t do what’s right.

Q. Who influenced your development as an artist?

A. Mostly other writers. I don’t just mean Sonia Sanchez and Nikki Giovanni and Ralph Ellison, I also mean Big Daddy Kane and Black Thought and KRS-One and Chuck D from Public Enemy — these are the writers when I was growing up that I wanted to be like. So I’m inspired by the entire literary continuum, which in my life includes principally hip-hop and hip-hop culture. The culture is what inspired me, the tradition is what disciplined me, and my people continue to push me forward.