Boston and New York were economic hubs of Colonial America. On the Eastern seaboard (or, as it was known then, the only seaboard), each city’s harbor and surrounding natural resources made it a critical center of commerce, trade, and industry.

Being on the coast used to be an asset. In a warming world, it’s a big problem. Both cities are highly vulnerable to rising sea levels.

This map of Boston, created by a Climate Central tool, shows areas vulnerable to a rise of five meters in satellite view. Click to embiggen.

Higher sea levels have been inevitable for some time, but recent research indicates that sea levels are rising faster on the East Coast than anywhere else. (Except, of course, in North Carolina.) Both cities are now developing contingency plans for higher seas and related storm surges.

Areas currently vulnerable to hurricane-related storm surge, from the New York Department of Environmental Conservation [PDF]. Click to embiggen.

Current projections suggest that sea levels could rise five feet by 2100, putting at risk a number of waterside facilities. The city is already working to accommodate the changes, building developments on higher ground, installing floodgates at the water treatment plant, and allowing landlords to move electrical equipment from basements to the roofs. But the panels are empowered to go further:

The legislation broadens the responsibilities of the advisory bodies, including requiring the adaptation task force to create an inventory of potential risks to vulnerable populations like the elderly and low-income residents of industrial areas where flooding also raises the risk of toxic spills. It requires the scientific advisers to meet at least twice a year to review the latest climate change data and to update their projections every three years. The task force is then required to submit its recommendations a year after projections are released.

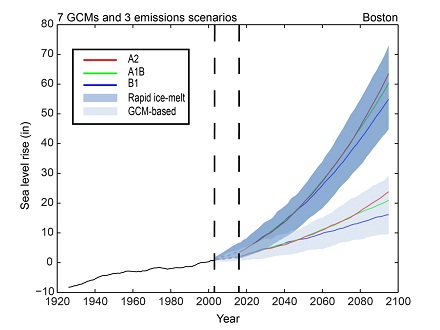

Projections of sea level rise in Boston from the city’s official site.

Boston is more at risk than Manhattan, lacking the protection of a Long Island and the distance of New York Harbor. It too recently completed an action plan on climate change, and is now identifying places where changes need to be made. A recent NPR story noted the ways in which development has been updated and infrastructure is being protected in an effort to curtail damage.

[C]ity officials have been studying the dangers and the possible effects of flooding on sewers and roads. The city is also undertaking a major environmental restoration project on the Muddy River to control flooding.

Essentially, the city is looking at the big systems, in the hopes of preventing flooding in housing projects in East Boston or in million-dollar condominiums in the historic Back Bay neighborhood.

Tedd Saunders, a resident of Back Bay, is a consultant who advises hotels on how to incorporate environmental sustainability into their operations. Under some scientists’ projections, his neighborhood could be completely flooded — the Venice section of Boston, perhaps.

“I think the ‘Venice section of Boston’ makes it sound like it’s more romantic than it might be,” Saunders says. “There would be no way of getting around.”

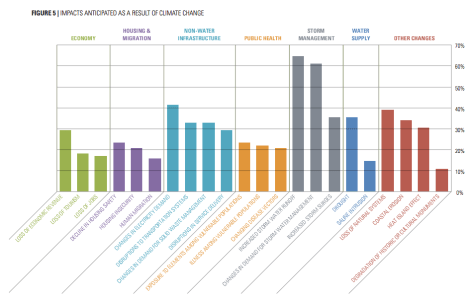

From MIT’s report, “Progress and Challenges in Urban Climate Adaptation Planning” [PDF]. Click to embiggen.

Magdalena Ayed lives in public housing near Boston Harbor. When NPR interviewed her earlier this week, she explained why she was worried.

“I love this place but sometimes I think about 10 years from now. I read a lot, and I’ve read the reports that this part of Boston will be basically underwater in 30 or 50 years. … What are our options? Where would we go?”

Those are the questions that Boston and New York hope no one ever has to ask.