Last month, we looked at a business owner in Pittsburgh who was forced to cancel plans to hire more staff when the city cut bus service near his office. The problem is not unique to Pittsburgh: The relationship between jobs and transit is an intricate one — albeit one that hasn’t received much study.

The Brookings Institution released a report today that provides some insight. “Where the Jobs Are: Employer Access to Labor by Transit” assesses the public transit access to jobs in urban and suburban areas. The findings:

- More than three-quarters of all jobs in the 100 largest metropolitan areas are in neighborhoods with transit service … Regardless of region, city jobs across every metro area and industry category have better access to transit than their suburban counterparts.

- The typical job is accessible to only about 27 percent of its metropolitan workforce by transit in 90 minutes or less.

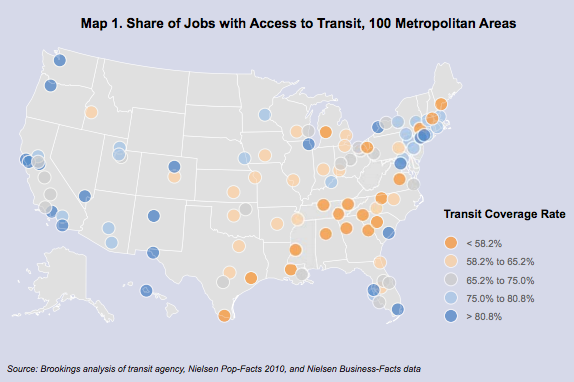

The first point — jobs accessible by transit in the 100 largest cities — is illustrated below, by city.

When a metropolitan area fails to extend transit into the suburbs, workers have a much harder time accessing jobs. Here’s an example of how that works for several cities, taken from the full report [PDF]:

For example, consider the cases of San Jose and Richmond. Both metropolitan areas offer transit service to over 97 percent of city jobs. But while San Jose’s suburban transit routes extend well beyond the city core, offering service to 84 percent of its suburban jobs, Richmond’s suburban routes stop close to the municipal borders, offering service to only 29 percent of suburban jobs. The end result is that San Jose’s overall transit coverage rate ranks fourth and Richmond’s ranks 94th. And Richmond isn’t the only metro that registers this extreme city/suburban dichotomy. Atlanta, Grand Rapids, and McAllen all show near-ubiquitous transit coverage in their primary cities and limited suburban coverage, pushing their overall coverage rates to the bottom quintile.

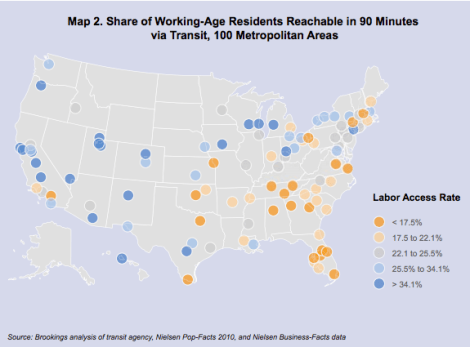

But even if a job is accessible by transit, that doesn’t mean that using transit to get to work is feasible. Below, a map of the second metric: the percent of a city’s population that is within a 90 minute window of a job.

One conclusion Brookings draws:

Taken together, these two accessibility shares provide a sobering account of the costs of continuous decentralization. While the majority of households and jobs are near transit stops — proving that metropolitan transit networks do reach most of our neighborhoods — the distances between people and their regional jobs are too great to generate higher accessibility rates.

Brookings includes a city-by-city assessment of labor access using public transit, if you’d like to see how your municipality fares. Pittsburgh, if you’re wondering, ranks 69th out of 100 [PDF] in labor access rate.