Robert Hammond. (Photo by Annie Schlechter.)

Excerpted from a longer interview in The Dirt.

Robert Hammond is co-founder and co-executive director of Friends of the High Line, the nonprofit conservancy that manages the High Line, a public park built atop an abandoned, elevated rail line on the west side of Manhattan. He and his co-founder and director, Joshua David, have just published a book about their experience called The High Line: The Inside Story of New York City’s Park in the Sky.

Q. In the beginning of your book, you say that early on, living in Chelsea, you’d seen parts of the High Line, “but never realized all the bits and pieces connected.”

A. I lived in the neighborhood so I had always seen it when walking around, but I didn’t think it was all connected. I really didn’t think that much about it until I read an article in the New York Times in the summer of ’99 that said it was threatened with demolition. The article showed that it was a mile and a half long running through the Meatpacking District and Chelsea, all the way up to Hell’s Kitchen near the Javits Convention Center. That’s when I first realized the whole extent of it.

I assumed someone would be working to preserve it. So many things in New York have preservation groups attached to them. But pretty quickly I found no one was doing anything for the High Line. I heard the proposed demolition was on the agenda for a community board meeting in my neighborhood so I went to my first community board meeting ever and sat next to Joshua, who I didn’t know at the time. By the end of the meeting, we realized everyone in the room was in favor of demolition except for us. So we exchanged business cards and we said, “Well, why don’t we start something together?”

Q. Which aspects of your strategy, in retrospect, proved to be most critical to moving the High Line forward in those early days?

A. Josh and I get a lot of credit for this great strategy. I think the most important thing we did was start the project, and it allowed other people to come along and help us get it done.

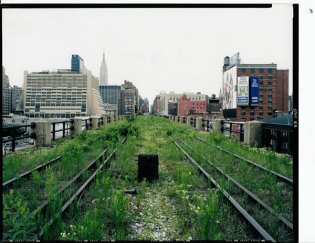

The High Line, before. (Photo by Joel Sternfeld.)

One of the things that really connected the landscape and the ultimate design of the High Line were the photographs by Joel Sternfeld. When Josh and I went up there, we realized what was right there in the middle of Manhattan. I first fell in love with the High Line from the street. I loved the structure, the rivets. But then when I walked up there, there was a mile and a half of wildflowers running right through the city. That’s what I really fell in love with: the combination of this wild landscape on top of this industrial structure in the middle of the city.

We knew most people were never going to see it like this, so we took our snapshots which just didn’t look that great. They didn’t really capture the impact of it. So I got a photographer named Joel Sternfeld to go up there, and over the next year, between 2000 to 2001, he took a few pictures in all four seasons. He ultimately published a book called Walking the High Line in 2002.

Josh and I think of him as the third co-founder because those photographs of the wild landscape are what really helped galvanize people. I realized the most effective way to bring people on board was to show them the photographs. Joel’s images really made the case for the project.

Q. As the High Line developed, it has helped spur literally billions of dollars of new property development. Was that part of the original plan?

A. It was. We knew that the High Line had to make economic sense in the long run, so we realized that for some people, pretty pictures weren’t enough. We also needed an economic impact study, which is a really powerful tool for people working on parks projects because landscape, park, and public space projects can have a tremendous economic impact. Too often, people just rely on what it looks like to make the case.

Q. Do you think the High Line’s success can be replicated in other cities?

The High Line, after. (Photo by Iwan Baan.)

A. There are certain projects I really like, which have their own integrity. A lot of them are generated by communities. There’s the Bloomingdale Trail in Chicago, which was originally based in the community and came from a few people who lived in the area. The Atlanta Beltline, which is a much bigger, ambitious project, started as one student’s thesis. The Jersey Embankment, right across the river, is definitely a community-based project.

A project has to have that spirit from below. I think the best ones are not trying to copy the High Line; they’re trying to be something new altogether. This is the test to determine success: whether they try to create something original, just like the High Line did, or not.

Q. What advice would you have for other community groups trying to save and transform local infrastructure and cultural assets?

A. The most important advice is just start it and experiment. Just try things. There are multiple ways to get started.

Now, a great way to do these things and galvanize a project is Facebook. Start a Kickstarter account — I’ve seen that working a lot now. One of the really important things is to raise money. It also helps start building the community. Whether someone gives $5, $5,000, or $5 million, when they give money they become more invested in the project. It’s literally skin in the game. It’s an important part of building an organization or a whole movement.

I have my personal goals for the High Line: one is that it’s a well-loved park by New Yorkers; two is that it gets better after Josh and I leave; and three (and most importantly) is that it inspires other people to start these kind of things — not just elevated rail lines, but any kind of project. You don’t have to have experience, you don’t have to have all the money, you don’t have to have the plans all set. Those things can come.