The story seems to change every five minutes. One recent report found that, for the first time since the advent of the automobile, cities are adding population faster than suburban areas. “Cities grow more than suburbs, first time in 100 years,” trumpeted the Associated Press.

The story seems to change every five minutes. One recent report found that, for the first time since the advent of the automobile, cities are adding population faster than suburban areas. “Cities grow more than suburbs, first time in 100 years,” trumpeted the Associated Press.

Now comes news that the most suburban of all suburban areas, the exurbs, have been the fastest growing places in the country’s 100 largest metropolitan areas — yes, even after the housing crash. The headline in The Atlantic Cities: “Exurbs, the fastest growing areas in the U.S.”

I’m sorry. Come again?

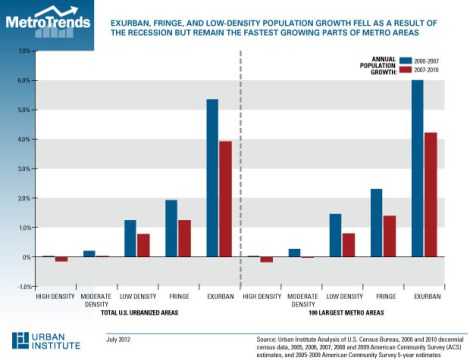

For starters, the two studies mentioned above are not as contradictory as the headlines make them sound. The study showing that exurbs outpaced the rest of large metro areas, done by researchers at the Census Bureau and the Urban Institute, looked at census data from 2000 to 2010. (You can find a short discussion by the authors here.) They confirmed what we already knew: Growth in metropolitan areas declined across the board following the collapse of the housing market in 2007. Nonetheless, exurban growth continued to outpace the rest of the metropolitan U.S. Here’s a handy graph:

The study showing that cities have surged ahead, done by the Brookings Institution, looked only at 2011, so it’s possible that we saw a shift toward the cities between 2010 and 2011. That might be less remarkable than it sounds: Because there are fewer people living in city centers than there are in suburbs, cities can show faster growth rates even while fewer people are moving in. Still, if there was a shift, it is made more dramatic by this new study, which shows that, in the four years prior, exurbs were still leaving cities in the dust.

It is entirely possible, however, that the 2011 numbers are a bunch of baloney. They’re drawn from the American Community Survey, an annual census count that is much less reliable than the full-blown, once-every-decade, door-to-door version. (We saw this in 2010, when the census dashed predictions, based on Community Survey numbers, of a mass migration back to cities.) Brookings also used counties for its comparison, rather than census tracts, which are much smaller and therefore offer a more fine-grained picture.

“In our opinion, counties are far too large to be used to define exurbia, as they contain many different area types,” Census Bureau researcher Todd Gardner wrote in an email. “Unfortunately, we can’t as yet tabulate the exurban population for 2011 [based on census tracts] because population figures are not available for census tracts for 2011. And even if those figures were available, we wouldn’t be able to tabulate the population using strictly comparable geography because of the substantial changes to tract boundaries that occurred with the 2010 census.”

In other words, it’s hard to tell what’s really happening right now.

There are other signs that the tides are turning in favor of cities, of course. Young people are spurning cars in favor of bikes and mass transit, and they’re putting off getting married and having kids — the traditional kiss of death for urban living. And as the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Kaid Benfield has pointed out, there are some indications that the housing market in cities has come back stronger than in the ’burbs. But the truth is that we don’t know whether cities are making a comeback vis-à-vis the suburbs, and we likely won’t have the numbers to prove or disprove it until the 2020 census data comes out.

So why should we bother trying to read the tea leaves of between-year census numbers? Why the endless brawling among academics over their contradictory analyses of the data?

In a word: money.

The federal and state governments make many of their funding decisions based, to some degree, on population estimates. If the suburbs are where the people are, rest assured that the suburbs are where the dollars will flow. If people are really moving back to the city, we have a stronger argument for pouring more of our tax dollars into public transit, parks, schools, and other services in the urban core.

The more services we provide, the more people are apt to show up. It’s a virtuous (or vicious, depending on your perspective) cycle: Population drives the money, money drives the population.

Which brings me to my final, and most important point: Unless we start investing more in cities, any real blip we’re seeing in terms of an urban population rebound is sure to be short lived. Just because young Americans seem to prefer urban living now does not mean that we’ll stay forever. Like generations before us, we may opt for the good life in the suburbs when kids arrive on the scene and we suddenly see the benefits of a big yard, good public schools, and the likes. And that would be seriously bad news not just for cities, but also for the planet, which is choking on quite enough of our auto exhaust as it is, thank you very much.

There are many other reasons we should be plowing more money into urban areas, of course. As a country, we spend $63.4 billion a year warehousing our citizens, mostly urban blacks, in prisons — more than any other nation on earth. Serious investment in education and social supports could end the school-to-prison pipeline and give a whole disaffected side of our society a fighting chance. (Just ask Geoffrey Canada.)

We spend billions more dealing with the health effects of our suburban, car-dependent lifestyles. Encouraging people to make good on their growing desire to live in the urban core could go a long way toward addressing that.

I could go on. Instead, I’ll just say this: Regardless of what the Census Bureau tells us, it’s time to invest in city schools, healthy urban food systems, bike and pedestrian infrastructure, parks, and mass transit. Failing that, America will likely remain a suburban nation, and that’s not good for anyone.