I stumbled upon James Hamblin’s profile of Jeff Wilson, a.k.a. “Professor Dumpster,” in The Atlantic. Wilson, college dean at Huston-Tillotson University in Austin, Texas, is highlighted for his daring challenge to live inside of a 33-square-foot trash container. It’s all part of the Dumpster Project, an experiment he’s developing with students to build a “low-impact, zero-net-waste” dwelling out of the trash container.

It was interesting to learn about how many items of convenience Wilson has stripped from his life to place himself basically in solitary confinement: He’s got no toilet or shower (he uses the university’s), no washer and dryer for his clothes (he uses the laundromat), and his wardrobe is reduced to a few pairs of pants and shirts, three hats, and “eight or nine” bowties.

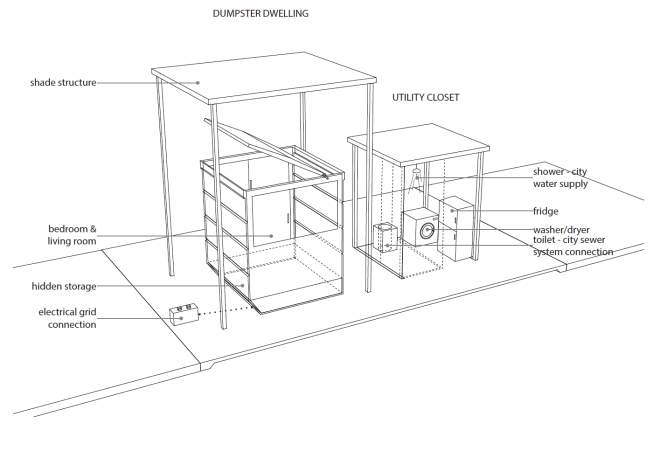

It’s basically a crib — though when finally complete, it will be something that could possibly revive MTV Cribs. Here’s what it will look like:

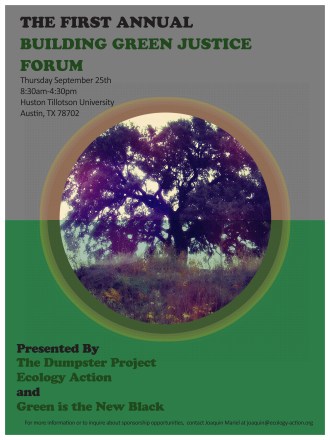

This was not mentioned in the story, but his school, Huston-Tillotson, is a historically black university. The student group Hamblin does mention, Green is the New Black, is the Huston-Tillotson student organization that is driving the Dumpster Project, and it is holding its inaugural Building Green Justice Forum on campus on Sept. 25.

Huston-Tillotson is spotlighted in the a report I just wrote about that highlights environmental work and progress at historically black schools. In particular Huston-Tillotson gets props for its Dumpster 101 curriculum, based on this project, and also its off-campus activity, like the STEM program it’s created for K-12 classes. It’s kinda criminal that this university didn’t make the Sierra Club’s or Princeton’s “greenest schools” lists based on this dumpster-ology alone.

Which brings me to another item left out of the story: That East Austin, where Wilson’s dumpster home and the university are located, is an area where African Americans and Latinos have historically lived segregated from the rest of the city. This racial segregation is by design, which you can read about in Cecilia Balli’s Texas Monthly story, or Luke Winkie’s in Vice. It’s part of why Austin is considered the 10th most segregated city in the nation.

East Austin is showing signs of gentrification, however. And Wilson himself could be easily taken for one of those caricatured-too-much hipsters encroaching upon black territory. He’s white. He has “eight or nine bowties.” But his Dumpster story charts a different path.

The lack of space in Wilson’s pod has pushed him into more intimate contact with his neighbors. As noted in the story:

He spent a lot more time out in the community, just walking around. “I almost feel like East Austin is my home and backyard,“ he said. He is constantly thinking about what sorts of things a person really needs in a house, and what can be more communal.

“What if everybody had to go to some sort of laundromat?” Wilson posited. “How would that shift how we have to, or get to, interact with others? I know I have met a much wider circle of people just from going to laundromats and wandering around outside of the dumpster when I would’ve been in there if I had a large flat screen and a La-Z Boy.” …

He’s also welcoming of anyone who wants to stop by the dumpster and talk sustainability any time. … On some nights, Wilson will stay with a friend, and students from the ecology-focused campus group Green Is the New Black will get a night to stay in the dumpster.

One of the biggest gripes about gentrification is that the invasive species moving in often seclude themselves from the natives, throwing off community chemistry. But Wilson’s dumpster is not a white sanctuary among black residents. Community is part of his intention. Also, since his place of rest is not a house, his occupation has not lead to someone else’s displacement, another prime feature of gentrification.

Now obviously we can’t all live in dumpsters to avoid pushing people out of their homes. But I like the kind of thinking that Wilson’s dumpster model hopefully inspires: How can we get in front of the problems often created in the gentrifying process? One way is not to ignore race, but rather to purposefully engage it.