The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Climatic Data Center has just released an overview of its new “1981-2010 Climate Normals” [PDF]. Meteorologist Paul Douglas, founder and CEO of Broadcast Weather, explains what this means:

NOAA just released the latest climate “normals” for the USA. When you hear the “average high” or “average low”, it’s a running, 30-year average. Data was just updated to show the first decade of the 21st century … For a look at how the new normals were calculated click here [PDF] — the full data set is set to be released on July 1. For continuity the same 5,053 weather observation sites were used. Averaged together (all reporting stations) the inclusion of the 2000-2010 data showed a 0.6 degrees F warming trend nationwide for the latest, running, 30-year averages.

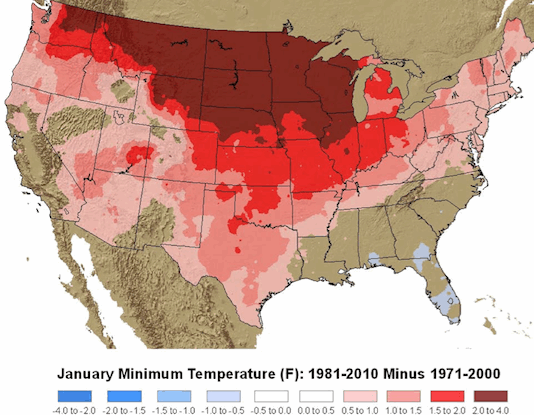

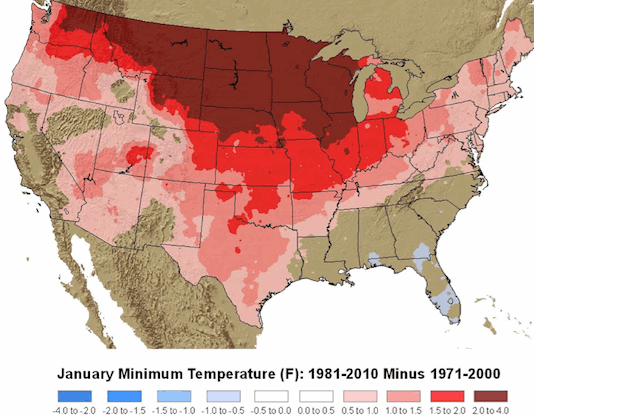

Here is the one “showing the difference between the 1981-2010 normals and the older 1971-2000 numbers. The data shows a distinct warming trend, factoring in the last decade’s worth of highs and lows, a 2-4 temperature increase for January low temperatures”:

Why does winter warming in the West matter? We’ve already seen the new U.S. Geological Survey study that found global warming is driving Rockies snowpack loss unrivaled in 800 years, which threatens western water supplies.

Then we have the voracious bark beetle, which just loves milder winters.

Climate change inherently favors invasive pests. Milder winters since 1994 have reduced the winter death rate of beetle larvae in places like Wyoming from 80 percent per year to under 10 percent. At the same time, hot-weather uber-droughts — aka “global-change-type droughts” — have made trees weaker, less able to fight off beetles. A 2008 Nature study looked at the beetle’s warming-driven devastation in British Columbia and concluded, “This impact converted the forest from a small net carbon sink to a large net carbon source.“

Last year, a Montana entomologist said of the bark beetle infestation: “A couple of degrees warmer could create multiple generations a year. If that happens, I expect it would be a disaster for all of our pine populations.” In other words, in a few decades, the new normal will be a disaster — assuming we don’t reverse greenhouse-gas emissions trends sharply and soon.

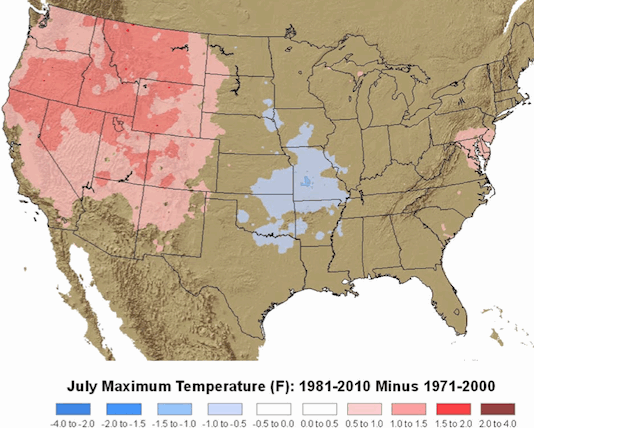

The summer maximum temps do not appear to have risen quite as rapidly as the winter minimums:

But don’t worry, the real summer heat is yet to come.

We are, after all, on track to warm up to 20 times more this century, than than we did in the last three decades.