When methane began bubbling out of kitchen taps near a gas drilling site in Pennsylvania last winter, a state regulator described the problem as “an anomaly.” But at the time he made that statement to ProPublica, that same official was investigating a similar case affecting more than a dozen homes near gas wells halfway across the state.

In fact, methane related to the natural gas industry has contaminated water wells in at least seven Pennsylvania counties since 2004 and is common enough that the state hired a full-time inspector dedicated to the issue in 2006. In one case, methane was detected in water sampled over 15 square miles. In another, a methane leak led to an explosion that killed a couple and their 17-month-old grandson.

Methane is the largest component of natural gas. Since it evaporates out of drinking water, it is not considered toxic, but in the air it can lead to explosions. When methane is found in water supplies, it can also signal that deeply drilled gas wells are linked with drinking water systems.

In many cases the methane seepage comes from thousands of old abandoned gas wells that riddle Pennsylvania’s geology, state inspectors say. But other cases, including several this year and the 2004 disaster that left three people dead, were linked to problems with newly drilled, active natural gas wells.

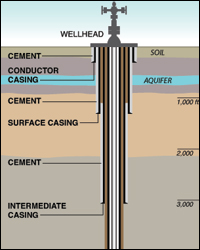

The issue came to the forefront in January when methane was found in the water at 16 homes in the small town of Dimock, in northeastern Pennsylvania. State officials cited Cabot Oil & Gas for several violations they say allowed the gas to seep out of the well structures and into water supplies there. The Department of Environmental Protection asked the company to encase its lower well pipes completely in concrete — a process known in the industry as “cementing” — and assured the public that the contamination in Dimock was rare.

The issue came to the forefront in January when methane was found in the water at 16 homes in the small town of Dimock, in northeastern Pennsylvania. State officials cited Cabot Oil & Gas for several violations they say allowed the gas to seep out of the well structures and into water supplies there. The Department of Environmental Protection asked the company to encase its lower well pipes completely in concrete — a process known in the industry as “cementing” — and assured the public that the contamination in Dimock was rare.

But according to a department spokeswoman, there have been at least 52 separate cases of what the state calls “methane migration” in the past five years. In two of the 2009 cases, regulators responded to complaints from more than 32 households and asked gas companies to supply clean water to at least a dozen homes with contaminated wells.

An undated report from the Pittsburgh Geological Society posted to the DEP’s Web site makes it clear that old wells and new drilling can lead to stray gas problems. “Although it rarely makes headlines,” the report reads, “damage or threats caused by gas migration is a common problem in Western Pennsylvania.”

Craig Lobins, the DEP regional oil and gas manager who initially described the Dimock case as an anomaly in interviews with ProPublica, said he still believes the frequency of contamination incidents is statistically insignificant.

Records show there are roughly 58,000 active gas wells in Pennsylvania. “We are just dealing with a very small percentage,” he said in a follow-up interview.

The case Lobins was investigating at the same time as the Dimock case concerned a string of problems in Bradford, a rural town 200 miles west of Dimock along the state’s northern border. Shortly after a contractor for Schreiner Oil and Gas drilled several dozen wells in the area last spring, residents began complaining of murky and foul-smelling tap water. When the DEP investigated, it found methane in three water wells and metals in six others. It asked Schreiner to supply water to eight homes, and the company has begun installing water treatment systems at each house. While no new gas wells have been drilled in the Bradford area, according to the DEP, the existing ones continue to operate.

Michael Schreiner, Schreiner’s president, declined to comment for this article.

Lobins said the problems in Bradford — as in many of the contamination cases across the state — stem from a bad cementing job around the core of the well. In most gas drilling, the well pipe is encased in layers of concrete to keep it isolated from surrounding groundwater. The concrete also contains the enormous pressure exerted on the system during the process of hydraulic fracturing, which pumps water, sand and chemicals to the well bottom to break up rock.

In Bradford, Lobins said, concrete was poured into the space around the wells but never filled the space — a sign of a possible leak. Because Pennsylvania does not have regulations that require inspections or testing of the concrete casing, the state didn’t notice the problem until methane began showing up in water wells. By then, the suspected concrete error had been repeated in as many as 27 different places, Lobins said.

Controlling the quality of cementing and well casing is widely viewed as the most important factor in protecting water supplies and ensuring the integrity of a well. A recent federally funded study of state regulations across the country (PDF), published by the Ground Water Protection Council, a consortium of state oil and gas regulators, industry representatives, and some environmental consultants, said that proper concrete casing is critical to environmental protection. While 96 percent of states, including Pennsylvania, have standards specifying that concrete be used to protect aquifers, the report found that one in five, also including Pennsylvania, do not require testing to confirm that the concrete used is strong enough for the job. That means that until water problems arose as a result of the casing problems in Bradford, the state had little recourse.

Controlling the quality of cementing and well casing is widely viewed as the most important factor in protecting water supplies and ensuring the integrity of a well. A recent federally funded study of state regulations across the country (PDF), published by the Ground Water Protection Council, a consortium of state oil and gas regulators, industry representatives, and some environmental consultants, said that proper concrete casing is critical to environmental protection. While 96 percent of states, including Pennsylvania, have standards specifying that concrete be used to protect aquifers, the report found that one in five, also including Pennsylvania, do not require testing to confirm that the concrete used is strong enough for the job. That means that until water problems arose as a result of the casing problems in Bradford, the state had little recourse.

“What they are doing is not a violation until the gas is leaving the borehole,” Lobins said. “We don’t know that until it manifests itself somewhere else.”

Lobins said the state is reviewing its regulations and that changes are planned to address both well casing and methane migration issues. But when asked what specific changes were being discussed, Lobins said he did not know. Similar questions went unanswered by Ron Gilius, the DEP’s oil and gas director, after they were submitted by ProPublica both in interviews and in writing.

For their part, Bradford residents were surprised to learn that their problems were not unique.

“They didn’t say that there were other problems similar to this,” said Lori Trumbull, who complained about her water but later found that it was OK. “They said that the odds of having water contamination from drilling operations is very rare.”

Fred Baldassare, the state’s dedicated methane migration investigator, said he has investigated water contaminated with drilling-related methane in numerous places across the state in recent years. In Bridgeville, two homes exploded when a well casing failed and methane seeped into their basements, he said. In Dayton, he said, residents were evacuated after a well casing failed and methane migrated into an adjacent abandoned well, blowing out its casing and travelling a third of a mile underground.

In Vandergrift, drillers stumbled across an old gas well that no one knew was there. Baldassare said that when the new well was hydraulically fractured, the intense pressure forced gas into the adjacent wells. It then percolated up through water and mud until it surfaced just feet from homes in a heavily populated neighborhood.

The most tragic Pennsylvania methane case began on March 5, 2004, in Jefferson County, about 80 miles northeast of Pittsburgh. According to Baldassare, gas seeped into the home of 64-year-old Charles Harper and his 53-year-old wife, Dorothy, from one of several adjacent wells being drilled by Snyder Brothers. The gas collected until it exploded and, according to court records and news reports at the time, reduced the home to “a pile of rubble.” Debris was found across the road, and insulation hung from trees 30 feet in the air. The bodies of the Harpers and their grandson, Baelee, were found buried in the debris.

Executives from Snyder Brothers did not return calls for comment. The company was sued in state court in Jefferson County and reached an undisclosed settlement with the Harper family.

State officials traced the methane’s geochemical fingerprint and determined it had come from one of three Snyder wells nearby. The investigation, however, remains open in part because Snyder has yet to comply with state orders to conduct pressure tests on the wells — orders delivered in 2005, according to Baldassare. But that doesn’t mean state officials aren’t sure about what happened.

According to Baldassare, the Snyder methane caused the explosion.

“In my view,” he said, “there was no uncertainty.”