A citizens group in South Portland, Maine, is hoping to beat back an effort by Big Oil to pipe tar-sands crude through their city. The group gathered enough signatures to put an initiative on the November ballot that would stymie oil companies’ plans, and now the activists are going door-to-door to convince their neighbors to vote for it.

South Portland is a relatively quiet place where major news doesn’t happen often, and lobstermen and clammers still make a living on the water.

When Vanessa Capelluti and her husband moved to their dream home on Casco Bay here a year ago, they didn’t know that oil companies had plans for this area too. Shortly after settling in, Capelluti found out about ExxonMobil and Enbridge’s quiet efforts to reverse aging oil pipelines [PDF] across Canada and swaths of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, aiming to pump heavy tar-sands crude from Alberta to the East Coast. The oil would travel right under the street in front of her home and on to the town’s shipyard, where it would be ferried out to international markets.

Before the heavy, almost-solid bitumen could be piped along the 1,800-mile route, the oil companies would have to thin it with a concoction of liquid natural gas and other hydrocarbons.

ExxonMobil currently holds permits to build twin smokestacks on South Portland’s waterfront, according to the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. The stacks would burn off the liquid gas and chemicals used for thinning.

There are already oil tanks and tankers in this port town, but the idea of bringing in tar-sands oil, considered one of the dirtiest fuels on the planet, was too much for Capelluti. The high-school art teacher joined up with Protect South Portland, a group of about 100 members that’s leading the anti-tar-sands fight.

“We became increasingly aware of what having tar sands pumped in meant,” said Capelluti. “We had to get involved.”

Bringing tar sands to town would “define South Portland’s image, and not in a good way,” said University of Maine environmental law professor Dave Owen. It would be a whole new level of dirty energy that’s counter to the town’s recent efforts to become an environmental leader, he said.

The ballot measure, officially called the Waterfront Protection Ordinance [PDF], would change the city’s zoning to block ExxonMobil’s smokestacks and a pumping station needed to bring the tar-sands oil into the shipyard.

“We can’t pick a bigger enemy than ExxonMobil,” said Andy Jones, who helps run Protect South Portland’s Facebook page. “But I’m hopeful.”

The big boys prepare for battle

ExxonMobil and Enbridge are also digging in for the fight.

They’ve hired a number of local attorneys, said Rob Sellin, a cofounder of Protect South Portland. The companies have also brought public relations firms on board, plus well-known New Hampshire political publicist Jim Merrill, a staffer for Gov. Stephen E. Merrill (R) in the ’90s and state director of George W. Bush’s 2000 general election campaign.

They recently conducted a phone survey asking residents how satisfied they were with the town’s mayor, Tom Blake, who is a staunch supporter of the ordinance and is up for reelection in November, Capelluti said.

From central Canada to coastal Maine, ExxonMobil, Enbridge Inc., and their partner companies have applied for permits and licenses to pipe diluted tar-sands bitumen. Since 2011, they’ve sent staffers to talk tar sands with Maine’s governor (see emails about the meeting [PDF]), filed paperwork in small towns throughout New England, sought several extensions of a key Maine environmental permit necessary for the project, and secured approval for one stretch of the line from Alberta to Ontario.

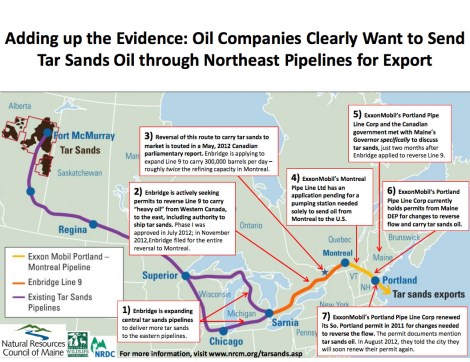

This map from the Natural Resources Council of Maine shows steps taken by the oil companies so far (click to embiggen):

All the while, however, company officials have repeatedly denied that they have intentions to reverse the pipeline that runs between Portland and Montreal.

In an interview with Grist, Merrill, now the spokesperson for Portland Pipe Line Corp., a subsidiary of ExxonMobil, denied that a reversal project was in the works: “What the pipeline [company] has said is they will always consider opportunities that may or may not arise. But there is no project at this time.”

Oil analysts and those who have been closely watching the oil companies’ moves say it’s only a matter of time before they file official plans to reverse the lines so they can pipe dilbit out of Alberta.

“With these kinds of projects, companies tend to operate under a cloak of secrecy,” said Tom Kloza, chief oil analyst with Oil Price Information Services, a company that tracks energy markets.

This strategy has worked in the oil companies’ favor, helping them avoid the national attention and scrutiny faced by new, larger pipeline projects like the Keystone XL and Enbridge’s Northern Gateway, said Danielle Droitsch, director of the Canada Project at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Old pipelines, new risks

The easternmost 236-mile stretch of pipe, called the Portland-Montreal Pipeline, crosses some of the most sensitive ecosystems in Maine, including the Androscoggin River, the pristine Crooked River, and Sebago Lake, which supplies drinking water for 15 percent of Maine’s population.

“It’s hard to come up with a more risky route for tar-sands oil to follow,” said Dylan Voorhees, clean energy project director with the Natural Resources Council of Maine.

The Portland-Montreal Pipeline was originally installed in 1950 to transport thinner, conventional crude, said Droitsch.

Activists are worried that using it to transport heavy dilbit could lead to a spill like the one that happened in Mayflower, Ark., earlier this year, when an ExxonMobil pipeline built in the 1940s ruptured and spilled hundreds of thousands of gallons of tar-sands oil.

“We followed that closely because we’re worried about what would happen here in South Portland with a spill like that,” said Jones of Protect South Portland.

An older manufactured date doesn’t necessarily mean a line is prone to rupture, said Richard Kuprewicz, president of Accufacts, a consulting firm that provides pipeline expertise to government agencies, the industry, and other parties.

But there are many questions that should be answered before an older pipe is converted to transport diluted bitumen. “What’s the type of pipe?” asked Kuprewicz. “What’s the condition of this pipe? When was it last tested?” For the Alberta-to-Maine project, those questions haven’t been answered — at least not publicly, he said.

Dilbit can be harsher on pipes than conventional oil. Even when it’s diluted with hydrocarbons, it can still be up to 70 times more viscous [PDF] than conventional oil, generating higher friction and temperatures in a pipe. It contains more abrasive sand particles and up to 20 times more corrosive acid concentrations.

It’s not easy to pump something “the consistency of peanut butter” through pipelines, said Kloza. “It’s like trying to squeeze into 32-inch pants.”

Said Kuprewicz, “The oil industry is making it seem like it’s the same as conventional oil, but it’s not.”

He’s seen a trend of oil companies trying to convert older pipes to transport dilbit, because under current federal regulations, conversions can be done “without making a lot of noise.”

Conversely, new pipelines such as the Keystone trigger several levels of federal scrutiny, including an environmental review.

A unique position

NRDC would like to see a federal environmental review of the Portland-to-Montreal pipeline reversal plan. The group has called on the U.S. Department of State to step in and order such a review before the project goes any further, but that doesn’t appear to be happening, said Droitsch.

Towns throughout New England have passed non-binding resolutions opposing the pipeline reversal, but they have no force of law.

Right now, South Portland is in a unique position to stop the pipeline plan. With the zoning ordinance on their ballot, city residents have a chance to keep tar-sands oil not just out of their town but out of the region.

“I think we have more leverage than anyone else, and I hope we have enough,” said Owen, the law professor.

Heading into the November vote, activists with Protect South Portland will be out trying to raise awareness among their fellow citizens.

“This [pipeline] is definitely in the works,” said Sellin, the group’s cofounder. “That’s why this ordinance is so important.”

Even if voters approve the ordinance in November, the oil and pipeline companies won’t back down easily. “There will be a challenge,” Sellin predicted.

But he said the group is preparing for that round of the fight too. “This ordinance is very defendable.”