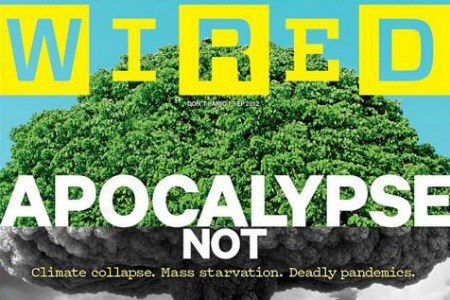

Good news, everyone. Wired is reporting that the world probably isn’t going to end in December. The bad news is how the magazine makes that argument.

It’s a clever article, this “Apocalypse Not,” framing previous apocalyptic predictions about the end of the world in the context of the Four Horsemen. In lieu of famine, pestilence, war, and death, author Matt Ridley assesses the threats from chemicals, disease, people, and resources. He walks through each “horseman” in order, dispatching as best he can past theories about how they would contribute to the eradication of humanity.

It’s a clever article, this “Apocalypse Not,” framing previous apocalyptic predictions about the end of the world in the context of the Four Horsemen. In lieu of famine, pestilence, war, and death, author Matt Ridley assesses the threats from chemicals, disease, people, and resources. He walks through each “horseman” in order, dispatching as best he can past theories about how they would contribute to the eradication of humanity.

In most of his examples, his point is made quickly and cleanly. There’s a massive exception, however: climate change.

The fundamental problem is that Ridley’s conceit makes it impossible to judge each argument entirely on its merits without hyperbole. He can’t ignore climate change, given the subject of the article, but he also can’t give climate change its due: He’s forced to classify it as a non-apocalypse a priori and to thereby dismiss it. After all, (1) the entire article is premised on our previous errors in assessing threats, and (2) the standard to which everything is compared is the apocalypse. I mean, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 killed 3 percent of the world’s population. But it wasn’t an “Armageddon” in Ridley’s formulation, an existential threat to Life As We Know It. Everything becomes an assessment on a binary scale, and one that proves his thesis before he begins: nothing before has destroyed the world; ergo, our current concerns won’t either. If one had, of course, Ridley wouldn’t be writing the article.

Proving that something isn’t apocalyptic is not a high bar. But it leads Ridley to dismiss threats wholesale in order to defend his (easily defended) thesis.

Take this paragraph, the crux of his case on climate:

We’ve already seen some evidence that humans can forestall warming-related catastrophes. A good example is malaria, which was once widely predicted to get worse as a result of climate change. Yet in the 20th century, malaria retreated from large parts of the world, including North America and Russia, even as the world warmed. Malaria-specific mortality plummeted in the first decade of the current century by an astonishing 25 percent. The weather may well have grown more hospitable to mosquitoes during that time. But any effects of warming were more than counteracted by pesticides, new antimalarial drugs, better drainage, and economic development. Experts such as Peter Gething at Oxford argue that these trends will continue, whatever the weather.

The argument then, flows like this. One of the threats raised by global warming is increased malaria. We’ve had a lot of success, though, in combating malaria; in fact, malaria’s impact has declined as we’ve fought it. Ergo, concerns about global warming are overblown and it won’t be the apocalypse.

Which is a bullshit argument! First, comparing our relative recent success in combating malaria to the haphazard and poorly funded efforts from last century doesn’t provide much insight into how we’ll fare against more widespread malaria using existing tools. Yes, once Bill and Melinda Gates and other advocates poured billions into the effort, we saw progress. It’s unlikely, though, that additional investment will continue to get the same rate of return.

The core premise here is that climate-change-bolstered malaria is less of a threat than alarmists would have you believe. Ridley’s argument is like saying that if you put 100 people in cars in a big arena and have them plow into each other, fatalities are reduced once you install airbags and seat belts, so the arena is safe for public use. But if you add another 1,000 cars, you’re going to be scrambling to find enough hospital beds / cemetery plots. That’s the threat of climate change — one that Ridley brushes off by noting how much good those seat belts did.

This is all beside the point. Even if the malaria argument held up, it would still only represent one ancillary concern stemming from global warming! It’s the James Inhofe school of climate-change debunking: one outlying data point renders the entire thing moot.

What’s amazing about Ridley’s essay is that the case presented above is the strongest refutation of the threat posed by climate change. Unless you include this:

The lesson of failed past predictions of ecological apocalypse is not that nothing was happening but that the middle-ground possibilities were too frequently excluded from consideration. In the climate debate, we hear a lot from those who think disaster is inexorable if not inevitable, and a lot from those who think it is all a hoax. We hardly ever allow the moderate “lukewarmers” a voice …

Except in cover stories in Wired. Let’s set aside that this isn’t an argument based on any fact. It’s a straw man, suggesting that there are two sides — predictors of “disaster” and deniers of reality. The political debate — and the debate is only political, not scientific — is actually between people who note the plethora of evidence that the world is warming and those who see it in their best interests to ignore that evidence. The moderates whose exclusion Ridley laments are those who agree that the world is changing but disagree with the scientific consensus on its impacts. They’re the outliers in the set of the science-accepters. And, pretty obviously, they include Ridley.

What follows that ellipsis in the quote above is a list of some people’s reasons for not worrying too much about climate change. Ridley merely repeats those conclusions without presenting the arguments behind them. Here, he suggests, is the middle ground between the “disaster is inevitable” camp and the “it ain’t happening” loons; here is the cause to be content. It’s question-begging: Since there exists a group that doesn’t think “disaster” is imminent, it isn’t, and therefore, climate change will not be apocalyptic. It’s the CNN school of fact presentation. One from this side; one from that side; the truth is in the middle.

None of this is meant to imply that Ridley isn’t sincere in his arguments or perfectly capable in his assessments elsewhere. It’s just that he has taken a legitimate premise — many past predictions of massive negative impacts have been allayed or incorrect — and tried to apply that model to climate change. As evidenced by the weakness of his argument, it didn’t work. And, unfortunately, he may very well leave the impression with Wired readers that climate change is just another false alarm, just another case of wild-eyed reactionaries carrying worn placards reading “The End Is Near.”

Climate change won’t destroy the world, but as we may already be seeing, it will certainly upend the lives we live. Apocalypse, not, to be sure. Just: the horror, the horror.