A vast plain of poisonous green slime stretching to the horizon, bobbing gently on the waves — that was the view of Lake Erie from Cleveland just a couple years ago. It could become a permanent feature if humans don’t scramble to do something about it.

Take a closer look at the boxed-in area in the above image (larger version), captured by NASA’s Aqua satellite in October 2011:

That’s toxic cyanobacteria swirling in the lake waters north of Cleveland. At the time, this slippery stuff covered nearly one-fifth of Erie’s surface, becoming the biggest bloom in the lake’s recorded history. It looked and smelled awful, turned fishing into a hook-detangling nightmare, and killed untold numbers of marine creatures by hypoxia.

Worse, the algae’s loaded with foul substances harmful to the heart, blood, and skin of many creatures. A dog that ingests one byproduct called microcystin can curl up and die within hours. (In humans it can cause flu-like symptoms, just in case you’re about to eat a bowlful.) The algae might also cause fish to change sexes.

The monstrous algae invasion represented a biological throwback to the 1960s, when tons of phosphorus in the Great Lakes seeping from agriculture, sewage systems, and industry summoned up bloated algal titans of an immensity never before seen. These blooms disappeared for the most part after the ’70s thanks to the U.S. and Canada enacting the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. But it appears we’re mired once again in the days of floating slime, with algae levels creeping up since the ’90s.

Who’s to blame here? The likeliest culprit is the agricultural industry with a helping hand from global warming, according to researchers at the Carnegie Institution for Science. The scientists conducted a detailed postmortem on the 2011 muck-up using satellite imagery and computer models. As in past years, the process began with farmers spreading phosphorus-based fertilizer in the fall to prepare for spring planting. Because of ideal growing conditions, they were especially fertilizer-happy in the autumn of 2010.

Much of this fertilizer was then washed into the lake by rain, where it acted as a “nutrient load” (aka dinner) for a legion of tiny microorganisms. The river washing was especially intense in May 2011, because a number of massive storms swept great amounts of sediment into Erie. The algae was not only well-fed but encouraged to grow by warmer temperatures and a weak water circulation that kept the stuff near the sunny surface. The result was a bumper year for algae farmers, which might actually become a thing in the future if the algae-based biofuel industry ever gets off the ground.

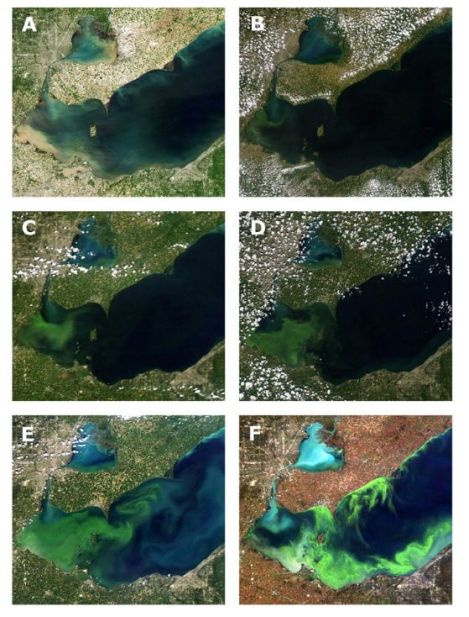

You can see the growth happening in this series of NASA shots starting in June 2011 (top left), where the swollen rivers are dumping solids into Erie’s western basin. The algae quickly covers much of the lake, resulting by October (bottom right) in contaminated water that resembles that ancient Ghostbusters Ecto Cooler drink:

With climate change leading to hotter seasons and more savage storms, Great Lakes residents might be seeing a lot more of these abnormally bloated algae blooms. According to a Carnegie write-up of the study:To determine the likelihood of future mega-blooms, the scientists analyzed climate model simulations under both past and future climate conditions. They found that severe storms become more likely in the future, with a 50% increase in the frequency of precipitation events of.80 inch (20 mm) or more of rain. Stronger storms, with greater than 1.2 inch (30 mm) of rain, could be twice as frequent.

The authors believe that future calm conditions with weak lake circulation after bloom onset is also likely to continue since current trends show decreasing wind speeds across the U.S. This would result in longer lasting blooms and decreased mixing in the water column.

The researchers say the potentially looming Algaeworld might be avoided if those in the agricultural industry use “better management practices.” Having the U.S. agree to a solid climate treaty probably wouldn’t hurt, either.

This story was produced by Atlantic Cities as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by Atlantic Cities as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.