Smith: Hi there!

Daly: Hello.

Smith: Apparently we are the voices in David’s head. It seems he can’t decide what to think about economic growth.

Daly: How droll, a Socratic dialogue post. 2003 called, it wants its blog trope back. You ever miss print journalism?

Smith: I hear you. No sense grumbling, though, we’re stuck in here. Might as well get on with it.

You’re here to argue that economic growth cannot continue on its present path. Make your case!

Daly: OK. The deal is, one way or another, global economic growth is going to end in the foreseeable future. The logic is pretty simple: Our growth depends on natural resources and natural resources are finite; ergo, we can’t grow forever. So says the Impossible Hamster:

Seems logical enough, doesn’t it?

Smith: Not really, but we can get into that later. Tell me why we should think growth will end any time soon.

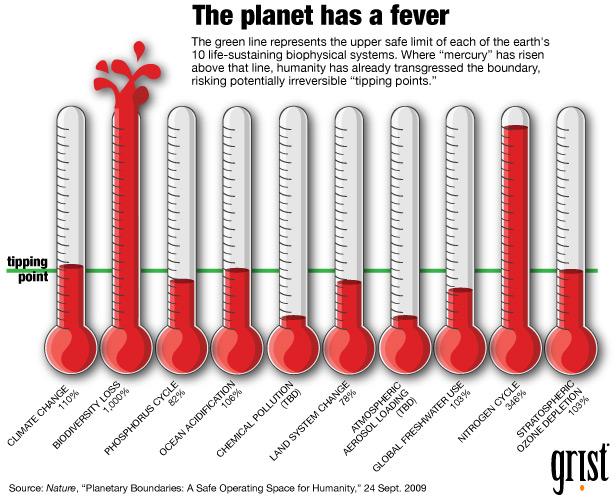

Daly: All right. According to scientists, we seem to be approaching numerous biophysical thresholds beyond which natural systems are going to start breaking down in unpredictable ways. This includes everything from species loss to freshwater depletion to ocean acidification to, of course, climate change.

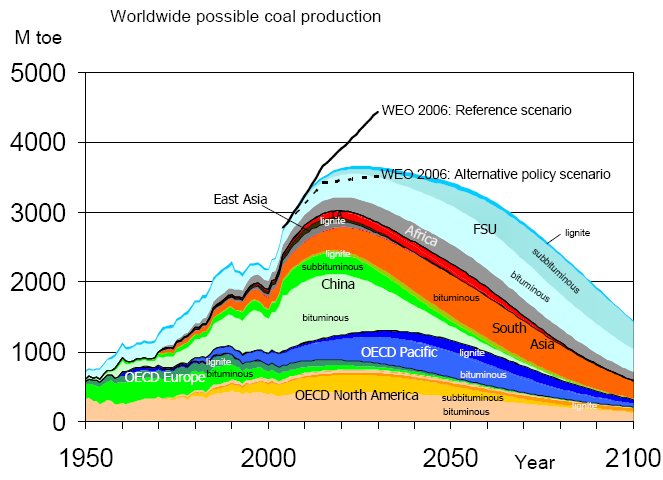

At the same time, we’re also approaching the “peak” of many natural resources on which the modern economy relies. This is most familiar from “peak oil,” but the same basic logic is true for other natural commodities like coal, natural gas, phosphorous, and even soil.

As economist Peter Victor says, “We’ve had 125,000 generations of humans, but it’s only been the last eight that have had growth. So what’s considered normal? I think we live in very abnormal times. And the signs are showing up everywhere that the burden we’re placing on the natural environment can’t be borne.”

The limitations on oil are starting to get traction in mainstream political and economic discussion, because we’ve reached a situation where there isn’t enough spare capacity in world oil supply to cushion prices against swings caused by unexpected events. (See: Libya.) This is what happens when demand outruns supply: not a steady rise in prices but large, painful, disruptive fluctuations. That’s the new normal.

If it weren’t behind a paywall, “A Crude Predicament” in Foreign Affairs would tell you all about it. Or check out this post from Kevin Drum, drawing on the work of economist James Hamilton, who notes that 10 of the 11 post-war U.S. recessions were preceded by a large spike in oil prices. From now on, Drum argues, “every time the global economy starts to reach even moderate growth rates, demand for oil will quickly bump up against supply constraints, prices will spike, and we’ll be thrown back into recession. Rinse and repeat.”

Smith: Yo Daly, I’ma let you finish, but market capitalism is one of the best ways of dealing with supply and demand of all time!

Daly: Cute. Anyway, I think oil provides a decent conceptual model for lots of other phenomena. Whether it’s soil, natural gas, or positive climate feedbacks, the closer you get to limits the more you get unpredictable swings in prices/supply/power/weather. That’s what the 21st century is going to look like. And that makes it extremely difficult to plan, site, fund, build, or insure major investments. It makes it difficult to grow!

Smith: Are you done?

Daly: No. But go ahead.

Smith: Folks who claim “biophysical constraints” are going to lead to economic catastrophe have a history of being, oh, how would one put it. Wrong. We’ve been hearing it ever since Malthus, and especially since the ’70s, but it keeps not happening.

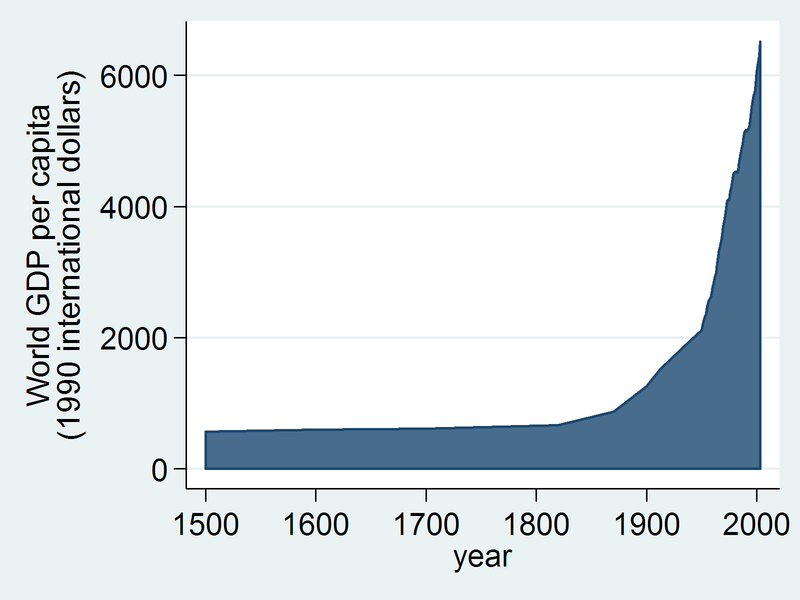

Here’s what happened to human wealth when democratic capitalism started catching on:

Obviously there’s more to this story than democracy and capitalism, but I think even you will have trouble denying that they’ve been an enormous net gain for humanity.

See over to the right there? Those are Human Development Index trends, amalgamating statistics on life expectancy, income, and education. Notice a trend? They’re going up. People are being brought out of miserable poverty by the hundreds of millions. (In China alone, 600 million over 30 years.) Humanity’s lot has been steadily improving.

See over to the right there? Those are Human Development Index trends, amalgamating statistics on life expectancy, income, and education. Notice a trend? They’re going up. People are being brought out of miserable poverty by the hundreds of millions. (In China alone, 600 million over 30 years.) Humanity’s lot has been steadily improving.

Obviously the world still contains far too much suffering and injustice, but the point you anti-growth people never seem to fully absorb is that insofar as there have been advances in security, dignity, and equality, they have been fueled by growth.

Liberals need growth even more than conservatives do. They have to overcome status quo bias. Social psychology and history both show that people are more inclined to be generous, more likely to care about the disadvantaged, during times of shared prosperity. If we want to spend on clean energy, health care, infrastructure, and innovation, we need money — tax revenue. For that, we need growth.

Demographic trends reveal the same need. There are more and more old people, fewer and fewer young people to pay for their health care and pensions. This is exactly what Biden was warning the Chinese about when he made his inartful comments on their one-child policy the other day. Unless countries want to sink into a pernicious spiral of higher taxes and lower productivity, they need … growth.

Daly: So what you’re saying is, growth.

Smith: Growth, man. Growth.

Daly: Here’s your problem. You think capitalism is limited only by human ingenuity, which is unlimited. You believe that Man Will Overcome.

And so, if soil’s being depleted, tweak the market to reflect that — raise soil prices. Price carbon. Price air and water pollution. Make sure the price of commodities reflects their externalities and watch the machine whir into action. The price signal goes to thousands, maybe millions of potential innovators at once, spurring them, through some mix of greed, ambition, and devotion to purpose, to devise solutions. Voila!

You think capitalism is a conceptual engine, that it transcends any physical substrate. As long as it incorporates correct information about relative value, it can continue growing in perpetuity.

But consider: What if the rocketing growth of the last 200 years has had much more to do with the physical substrate than you imagine? What if we’re just uncommonly clever primates who figured out how to unlock the power of fossil fuels? If that’s true, if our economies are mere subsets of the global ecosystem, utterly dependent on it for steady supply of resources, and we’re about to overshoot its carrying capacity, then … we might just go back to shivering in the dark.

For a less florid description of the problem, check out two of Richard Heinberg’s more recent books, Peak Everything and The End of Growth. One of the points he makes is that there’s no way to make renewables add up to the total energy that fossil fuels provide today, even with generous assumptions. To make up the gap with living standards intact, you need a truly enormous amount of conservation and efficiency. We’re going to have to start decoupling capitalism from resource consumption — dematerialize, move to a steady state economy — and do it fairly quickly.

Smith: We also need to make sure that every young girl in America gets the chance to braid a unicorn’s mane. I won’t have a child left behind!

Daly: Yeah, ha, I get it. It looks impossible. But the point is, the dematerialization will happen one way or another. Either we’ll do it on purpose or it will get done to us. Just because we have trouble imagining it doesn’t mean it’s not coming.

Smith: Nice modern civilization you got there. Shame if anything happened to it.

Daly: Don’t blame me. Blame Mother Nature.

Smith: Here’s the thing. We’ve been doing really well for 200 years with capitalist growth. Combined with some progressive taxation and redistributive programs, it’s the best way we’ve figured out to raise the living standards of the most people. It’s working well for us to this day, notwithstanding the current messiness.

You want us, on the word of a faction of economists, engineers, and wonks, to … what, exactly? Nationalize and close coal mines? Ration commodities? Follow China’s one-child policy?

Daly: Low blow, friend. I want to reduce population growth by empowering women.

Smith: Fair enough. Whatever, I admit it: it sounds impossible to me. Ceasing growth would give you two options: let the less fortunate suffer and die off, or radically ramp up redistribution — i.e., take tons more money from rich people and give it to poor people. The thing about rich people is, they really don’t like that. And it turns out, being rich, they have quite a bit of political clout. Today’s rich people aren’t attached to any country; they can move capital about as they please, punishing countries that dare to tax them excessively. Are all countries going to agree to aggressively tax the rich at once? Who’s going to prevent cheating?

I have to say, if you’re right that these biophysical thresholds and resource limits are looming around the corner, ready to abruptly reverse the progress of the last several hundred years, then sh*t, never mind taxation, we’re probably doomed to Mad Maxation. (Like that one?) The idea that we’re going to become radically more egalitarian, with substantially more modest material expectations, and we’re going to do so voluntarily and peacefully, in less than a century … that’s unicorn porn.

I hear lots of happy ideas from the anti-growth folk, but I’ve never heard anything even close to a practical political plan to get from Point A — a country gripped by fears over the deficit, suspicious of government, hostile to taxes, leery of social engineering — to Point B, a vision of the future that would make John Lennon blush. “Imagine there’s no growth …”

Until that plan emerges, I’m going to stick with trying to wring incremental gains for justice out of social democratic capitalism. It doesn’t work as well as one might like, but nothing else seems to work at all.

Daly: You lack imagination! A few more wild swings in gas prices, another hurricane or drought, a resource war or two … things change quickly. We need to be working toward reform now, so we’re ready when that moment comes.

Smith: Whatever you say, Comrade.

Daly: I guess we’ll leave it there.

Smith: See you next time. Unless David gets psychological help in the interim.