This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Huge sea-level rises caused by climate change will last far longer than the entire history of human civilization to date, according to new research, unless the brief window of opportunity of the next few decades is used to cut carbon emissions drastically.

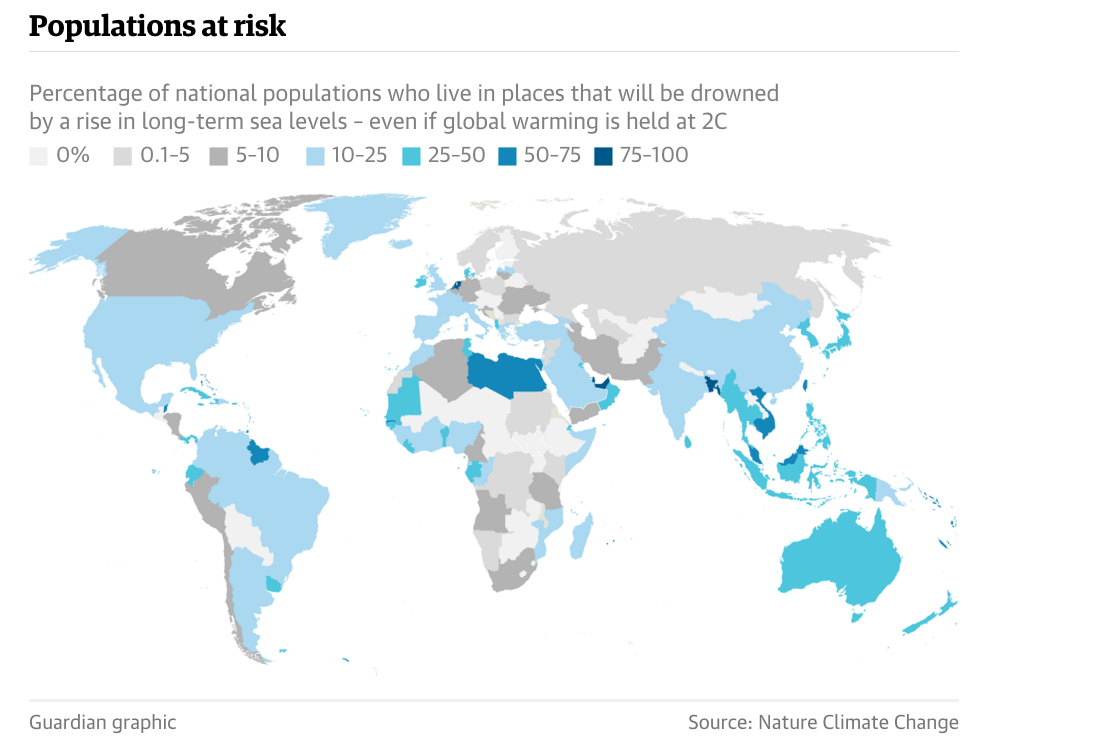

Even if global warming is capped at governments’ target of 2 degrees C — which is already seen as difficult — 20 percent of the world’s population will eventually have to migrate away from coasts swamped by rising oceans. Cities including New York, London, Rio de Janeiro, Cairo, Calcutta, Jakarta, and Shanghai would all be submerged.

“Much of the carbon we are putting in the air from burning fossil fuels will stay there for thousands of years,” said Peter Clark, a professor at Oregon State University in the U.S. who led the new work. “People need to understand that the effects of climate change won’t go away, at least not for thousands of generations.”

“The long-term view sends the chilling message of what the real risks and consequences are of the fossil fuel era,” said Thomas Stocker, a professor at the University of Bern, Switzerland, and also part of the research team. “It will commit us to massive adaptation efforts so that for many, dislocation and migration becomes the only option.”

The report, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, notes most research looks at the impacts of global warming by 2100 and so misses one of the biggest consequences for civilization — the long-term melting of polar ice caps and sea-level rise.

This is because the great ice sheets take thousand of years to react fully to higher temperatures. The researchers say this long-term view raises moral questions about the kind of environment being passed down to future generations.

The research shows that even with climate change limited to 2 degrees C by tough emissions cuts, sea level would rise by 25 meters over the next 2,000 years or so and remain there for at least 10,000 years — twice as long as human history. If today’s burning of coal, oil, and gas is not curbed, the sea would rise by 50 meters, completely changing the map of the world.

“We can’t keep building seawalls that are 25 meters high,” said Clark. “Entire populations of cities will eventually have to move.”

By far the greatest contributor to the sea-level rise — about 80 percent — would be the melting of the Antarctic ice sheet. Another new study in Nature Climate Change published on Monday reveals that some large Antarctic ice sheets are dangerously close to losing the sea ice shelves that hold back their flow into the ocean.

Huge floating sea ice shelves around Antarctica provide buttresses for the glaciers and ice sheets on the continent. But when they are lost to melting, as happened the with Larsen B shelf in 2002, the speed of flow into the ocean can increase eightfold.

Johannes Fürst, at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany, and colleagues calculated that just 5 percent of the ice shelf in the Bellingshausen Sea and 7 percent in the Amundsen Sea can be lost before their buttressing effect vanishes. “This is worrying because it is in these regions that we have observed the highest rates of ice-shelf thinning over the past two decades,” he said.

Avoiding the long-term swamping of many of the world’s greatest cities is already difficult, given the amount carbon dioxide already released into the atmosphere. “Sea-level rise is already baked into the system,” said Stocker, one of the world’s leading climate scientists.

However, the rise could be reduced and delayed if carbon is removed from the atmosphere in the future, he said: “If you are very optimistic and think we will be in the position by 2050 or 2070 to have a global scale carbon removal scheme — which sounds very science fiction — you could pump down CO2 levels. But there is no indication that this is technically possible.” A further difficulty is the large amount of heat and CO2 already stored in the oceans.

Stocker said: “The actions of the next 30 years are absolutely crucial for putting us on a path that avoids the [worst] outcomes and ensuring, at least in the next 200 years, the impacts are limited and give us time to adapt.”

The researchers argue that a new industrial revolution is required to deliver a global energy system that emits no carbon at all. They conclude: “The success of the [U.N. climate summit in] Paris meeting, and of every future meeting, must be evaluated not only by levels of national commitments, but also by looking at how they will lead ultimately to the point when zero-carbon energy systems become the obvious choice for everyone.”

“We are making choices that will affect our grandchildren’s grandchildren and beyond,” said Daniel Schrag, a professor at Harvard University in the U.S. “We need to think carefully about the long timescales of what we are unleashing.”