Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction initiative, celebrates stories that offer vivid, hope-filled, diverse visions of climate progress. Discover more cli-fi collections. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

There’s a voice in the darkness: “Did I hit my head?”

And a reply: “I have insufficient information to answer that, Ysolt.”

There’s a darkness, she knows that much. But a minute ago it was light. She does not like time passing without her awareness; sleep has been a mild torture since she was a little girl. But actually, she’s never been knocked out before, never lost time in a blink like this. She tries to touch her head, which hurts, and finds that she cannot move her arms.

Perception returns first, lagging behind memory. She waits, heart pounding, for all the information to come to her. She is buried up to her collarbones, splayed arms embracing a load of dirt. A faint, dusty smell of bruised sage rises to her nose. The darkness is not quite absolute; as her vision clears, she notices a single gray spear of light falling from far above.

With her glasses knocked off and, presumably, buried alongside her, it takes a while to realize what she’s looking at. Ah: light entering not through the usual place (the roof, which is transparent) but somewhere else (the wall, which is supposed to be opaque).

That’s right. She remembers now. The outside came in.

As she digs herself out, she recites times tables out loud, basic formulas of geometry and trigonometry, reassuring herself that this invisible world of numbers and variables is still there, as real as the soil cupped in her hands. That the world still makes sense.

* * *

The really irritating thing, of course, is that they knew the storm was coming — everybody knew; there had been alerts, broadcasts, emails, and texts a full week in advance. To the day, almost to the hour, its arrival was known. The pods of her town, Fourseven, had prepared for it as they would for a tedious, unwelcome, but inevitable houseguest.

Knowing that they could not outpace it, the usual shelter-in-place protocols took precedence. Everyone walked their pod to a nice flat spot, retracted the legs into the body, topped up their fridges with snacks and their tanks with water, charged all their devices, and made sure the littles had extra diapers and the elders had extra meds. Then the pods hunkered down, each linked to each, to wait it out. Five or six hours, the projections had said. The usual inconvenient but brief prairie tantrum.

But it hadn’t been, it hadn’t, and Ysolt, still digging, her fingers chancing across her glasses — aha! wonderful — finds herself angrier at the weather alert than at the weather itself. How dare it be wrong!

“Living room light,” she says, and nothing happens. Only her primary drone, Dif, steps into view, a volleyball-sized body balanced on a dozen finger-thick legs, intact though dented all over, his panels loosened by impact so that dark veins of circuitry show through the sand-etched steel.

“What happened?” Ysolt asks him.

“It appears that the alert for the weather event named ‘Lelesi-72,’ forecast to be a Category-B windspeed event, has been retroactively canceled and replaced with an alert for a weather event named ‘Makelvic-72,’ a Category G.”

Ysolt has never heard of Category G. This, she feels, explains some things.

Freed, she checks herself over — bruises, scrapes, but nothing sprained or broken. The influx of dirt must have acted like an airbag. She feels through the short, dark feathers of her hair, seeking out a bump or blood, but her fingers come away clean. “Where’s my phone? Are the other bots functioning, Dif?”

“Samsung Phone is not within the five-kilometer location radius. All others nonresponsive except for Module 32,” Dif says.

Module 32’s muffled voice rises from beneath the dirt: “Diagnostic recommended. Contaminants inside mechanism.”

“Yes, well,” Ysolt says. She moves tentatively across the wreckage, trying to get her bearings, only half-listening to Dif as he announces his findings from the house’s various accelerometers and motion detectors. The house itself tells a pretty clear story: Fourseven hunkered down but didn’t bother anchoring, as it would have if a heat dome tornado had been forecast, and so the town had been torn apart from itself. Intact pods are out there somewhere walking to find one another, following their GPS beepers, a shining herd of tortoises in the sun; a few search-and-rescue pods are on the hunt for the missing, like Ysolt.

Except, she now suspects, they won’t find her.

For her house is at the bottom of a crevasse, and that’s why there’s the barest fleck of daylight coming in. Her GPS beeper is working fine, but down here the signal is unlikely to be picked up. She climbs through the opening, the tiny metal plates on her jeans jingling against the edges of the carbon fiber, and cautiously looks around, bracing her hands on the outside so she doesn’t slip back in. For a moment the scale of the problem doesn’t hit her, and when it does, she feels sick to her stomach. Her house — the most precious thing in her life, the pear-cut gem she often smiles at as it glitters in the sunrise, a masterpiece of engineering and construction meant to ride out any kind of weather — is wedged vertically between two cliffs of gleaming whiteness.

She is overtaken by panic for a second, her lizard brain insisting that her house, and she herself, and her two remaining drones, are about to be eaten, that these are teeth, white teeth, oh my God, but it passes, and she calls to Dif to come give her some light.

“I can’t get up there,” Dif says. “However, you could lift me.”

“Never mind,” Ysolt says. “I’m coming back in.” There’s a lot of the whiteness scattered around, all of suspicious regularity and angularity, and she knows what she’ll find even before she picks up a chunk and climbs carefully back down.

“Salt,” she says to the waiting drone, giving the chunk a desultory lick, then holding it in front of his sensors. “We’re in a salt crack.”

“This is not a fortunate occurrence,” says Dif.

Ysolt closes her eyes and instead of hurling the chunk at him, she puts it in her pocket, willing herself to stay calm. In her head she hears her mother’s voice, five years ago: Izzy, darling, you know you can stay with us as long as you like … Yes, and this wouldn’t be happening if she had.

Almost everyone in Fourseven — in every town they encountered, too — lives in a bigger, heavier pod, meant to fit ten or 12 people. It is so much the norm that the pace of the town’s movement as a whole is exactly calibrated to those big pods. Only a handful of pods are as small as hers; she allows herself a moment of both bitterness and relief, thinking that everyone else is most likely — to a reasonable degree of probability — fine.

After the weather started going wild, after the cities emptied out, much of humanity discovered somewhat to their surprise that what they had done initially out of panicked necessity — uprooting, becoming mobile — suited most folks rather well. Now a relaxed nomadicism has become ingrained, life as normal. No more did you have to stay in one place and wait for the big one, whatever that might be, to hit you; now you could walk away with all your friends and family, and eat heirloom popcorn while watching the news about the big one hitting the place you had just left.

But just as in the old days that Ysolt has read about (for she reads more than anyone), there are always people who feel born out of time, or in the wrong place, or to the wrong family, or just … wrong. And when she picks up vintage copies of Architectural Digest or Better Homes & Gardens, she sees herself in those pages; unlike almost everyone she knows in these moving towns, she has never enjoyed living with people. She always craved the privacy side of mobile microsufficiency more than the communal side of it, hated and feared chaos and unpredictability (choosing a town that moved in a loop instead of scribbling across the landscape like a bark beetle), strove even to get a predictable, detail-oriented job that would let her work alone as much as possible except for virtual meetings (curriculum development, mainly math and science, for junior high and high schools). So, going to plan, she did all her calculations on down payment and mortgage rates, saved up, bought her own pod, moved out …

… and now it and she are stuck in a hole in the middle of nowhere with nothing but one drone that’s buried and useless (and beeping pitifully for release, she notices; she’ll go dig it out in a minute) and another with an incredibly annoying attitude that she would have gotten rid of years ago if he hadn’t belonged to her sister. For the same reason, she finds she cannot reset Dif to his factory-standard personality. It’s not so much that he’s some kind of connection to Vivi; it’s more that after being owned by Vivi for so many years, he’s now the only way to approximate, even slightly, the gentle endless bickering and banter and familect of the sisters.

Her house being in this crevasse is not the end of the world. She just needs… she needs more information. And then she’ll figure this all out. It’s what she does. It’s who she is.

“What’s the plan?” she says out loud.

“I — ” begins Dif.

“You, hush.”

She can’t remember the fall down here, which she thinks is fortunate; it must have been sudden, terrifying, violent. Bonk bonk bonk, the pod crashing and thudding between the hard white walls, so that it was already torn open, integrity gone, when the tornado poured the rest of its excavated land down here. This happens sometimes, she knows. It is grim knowledge in several respects. One, that centuries of industrialization desiccated the land and poisoned the skies until desertification set in and the stabilizing vegetation died back, encouraging storms of ever greater devastation, until you eventually got to things like this that stripped off soil until they tore loose the fossilized beds of ancient seas. There were no cracks or cliffs on their maps, all the latest ones based on satellite photos; these salt mountains were created by the wind.

Two, of course, that a storm like this killed her sister.

Her body recalls the days after the death with a sensation of falling — from a greater height than this, into a greater darkness. One moment it was as if she and Vivi stood in a safe place, together. The next she was alone, slapping away the hands that sought to help her. Ysolt had been 19 — young enough to believe she could be a hero somehow, save the day; and also too young to realize that no one can ever save the day all by themselves. She couldn’t save Vivi, so why should anyone come to save her now? Even as she thinks it, she knows it’s ridiculous, yet the guilt is heavy and real in her chest. She forces herself to set it aside and return to the moment.

“Report,” Ysolt says over her shoulder to Dif, whom she has lifted out onto the surface of the house (not an easy task, involving two knotted scarves and most of a roll of tape).

Dif says, “Primary power is at 19 percent, and the grid connection is down. I suspect mechanical damage. Backup storage is inaccessible and I am unable to connect to remote diagnostics.”

“Inaccessible — oh, you mean buried.”

“Yes.”

“Is our beeper working?” She points with her half-eaten granola bar at the green light faintly flickering at the highest point of the curved roof, normally the part that would protrude in a sandstorm, now wedged firmly against the far wall of salt.

“I believe so,” Dif says. “And its battery is nearly full. The problem is that the signal is blocked from reaching the surface.”

Ysolt nods. There’s a protocol for this, of course: The S&R team makes a grid, paces the lines, sends up drones once the conditions are safe, searches all along the spectrum of visible and invisible signals. But the house is very, very far down. She hadn’t realized quite how far until she climbed out and did a proper recon.

“Options?” she asks Dif. I’m not trained for this, she wants to add, any of this, I’m a teacher, there’s a system in place, I like the system, I don’t know what to do when it fails … but she suspects the self-pity will be more corrosive to her situation than the salt, and she pushes it away.

“I recommend an ascent to surface,” Dif says. “Given available data.”

“Given … what? You just said we’re at less than 20 percent battery, which would barely keep us going on the flat, and the wires got knocked loose. And look at our legs!” It had taken her almost an hour to check them, trying to keep her footing on the angled surface, sliding in the loose sand, salt, and debris. She hadn’t even been able to reach three of the legs on the underside, tangled in a bubbly mass of leaves where it looks like a whole greentumble forest got uprooted and poured down here. “As best I can tell, we’ve got two broken legs, five maybe functioning ones — they look okay, anyway — and three I can’t even tell.”

“Not the house,” Dif says after a moment, as if running her statement through his interpretation database a few times.

” … Oh.” Ysolt’s stomach turns to ice, a strange and sickening sensation in the heat. She almost regrets stopping for a meal, and wonders dimly whether it will stay down. She can just, if she tries, imagine climbing up, perhaps with Dif’s help (or, more likely, with her hoisting him up; his legs are very good manipulators but they are not cut out for mountaineering). But that means she must imagine leaving her house down here, and that is unbearable. She doesn’t have much but what she has is all in there — and she has worked for years not only to acquire it but to justify its acquisition, along with everything inside, every book, every painting, every memento. The houseplants she’s raised from her parents’ clippings; the fulgurite she and Vivi found at Wayale Lake after the storm; her great-grandfather’s painting of a crumbling skyline, handed down every generation, by silent consensus, to whoever liked weird old things the most. Her house contains every reminder of, and bulwark against, a world of chaos, a world in which she controls nothing and is at the mercy of everything.

“No,” she says, and crams the last of the granola bar into her mouth, putting the wrapper in her pocket. “Definitely not. We’re not leaving the house. What’s the rest of the list?”

“List?”

“List of options.”

” … That was the list.”

Hmm. She gets up, dusting her hands. “Definitely not,” she repeats. “I’m going to go dig out the batteries and Module 32. You, stay up here and get all the legs free.”

* * *

“We are rotating! We are not in control of rotation! I repeat—”

“One more step!”

“I recommend against it! Ysolt! Are you able to hear me?”

“Oh for God’s sake — fine, stop, all stop! All stop.”

The silence is sudden after the sand-gritted shrieking of the servos; even Dif is not moving, clinging to the roof with all his legs splayed out like a slapped spider. Ysolt realizes she is panting and lightheaded, and tries to slow her breathing. “All right,” she says after a minute, when she is sure she can speak. “Maybe you were right about my plan.”

Dif, to his credit, says nothing. She wonders if drones can go into shock and whether it would be helpful to put a cold towel on the back of his neck, except that he hasn’t got a neck and she hasn’t got a cold towel. Truthfully, she hadn’t thought this would work. It had been exciting to reach the battery compartment (and dig out Module 32 who, as a cleaning drone, exclaimed in dismay and immediately began emptying the dirt out of the house, so that was helpful).

It hadn’t even taken her all that long; Ysolt, like Vivi and most kids her age, spent several summers working for the Ministry of Carbon Management, spreading trees and oil-eating fungus pucks, seeding greentumble forests, setting up vertical micro-turbines (a competitive job market for that one, as good installers got really good money — they were only about five feet tall but incredibly awkward and heavy), and — crucially — digging thousands and thousands and thousands of small crescents to catch rainwater for newly-planted areas. So she still had all her standard-issue shovels, as well as all the muscle memory, to get the batteries cleared in half an hour.

Once she cleaned out the compartments and Dif hooked the wires back up, there was more bad news, though. The main battery was genuinely at nineteen percent — due, it seemed, to a cracked anode rather than actual power drain — and adding the backup battery only took them to 33 percent. It had been Ysolt’s unilateral decision to turn off everything else in the house and send all the power to the legs in an attempt to climb back up. But the legs were working irregularly without full power, and the house had started to spin and backslide, and …

“Don’t you dare say I told you so,” she adds to Dif, who still does not reply.

Her stomach is churning; she waits for it to subside. This isn’t supposed to be happening, none of this is supposed to happen. She imagines her mother and father’s panic up there somewhere; imagines them trying to keep their voices calm as they speak to the rescue team. She imagines their big, familiar pod, too heavy for any storm to pick up and toss around. She imagines her little nook there, still with the quilt her grandmother made her (where is grandma these days, anyway? Her town moves at quite a clip). She imagines her sister’s nook next to it, close enough for them to hold hands as kids, red-haired Vivi, always the adventurer, fished out of the sand …

She’s crying, unexpectedly, head in her arms. The house didn’t keep her safe and it didn’t keep Vivi safe and the world isn’t safe and everyone raised her to believe it was but it isn’t. She’s 26 years old and she’s going to die down here and it isn’t fair, it’s not fair. The volume of a cylinder is pi r-squared h, seven times eight is 56, force equals mass times acceleration. She’s spent her whole life wanting to be alone without learning the basic lesson about what happens when you are alone. For decades people have embroidered their clothes with bits of metal and decorative wire both because it looks neat and so that if you’re buried, someone can use a pinfinder to locate you. It’s why there were nails driven into the concrete sidewalks of old, fixed cities: an unmoving point of metal, a surveyor’s mark. The old cities couldn’t move away from their dangers. Sine is the opposite divided by the hypotenuse. The square root of …

“Ysolt, far be it from me to comment on human physiology, but you probably need to hydrate. And replace some electrolytes.”

She looks up, dazed. It has gotten dark enough that Dif can only be perceived by the small red lights behind his sensor panel, so that it seems as if a floating rectangle is speaking to her. One manipulator is clamped surreptitiously onto the hem of her jeans, the others hanging onto the roof. As if she would not notice this tiny act of grace. She licks her lips, tasting the salt of her tears and sweat, the salt of the walls surrounding them, a slight shock of bitterness.

“In a minute,” she says slowly. She is thirsty. “But … ” There’s lots of salt around her; she still takes the piece from her pocket, now dusted with lint, and holds it out to the drone. “Can you check this for toxicity?”

“I can’t do a detailed analysis of — “

“No, no, I meant … you know, your potable water straw. Can you see if this is sodium chloride?”

The red lights flicker as Dif extrudes a thin gold-plated probe and feels the surface of the salt chunk. “Sodium chloride is present,” he says. “With significant inclusions of potassium, magnesium, and calcium.”

“But it’s all chlorides?”

“Would you like the statistical analysis? It’s accurate to within a — “

“I have,” Ysolt says, cutting him off, “another idea.”

“A more rational one?”

“Not really,” Ysolt says, surprising herself. “I think a statistical analysis would show that the plausibility level is high but the probability level is low. Anyway, water first, and then I’ll explain.”

* * *

Only after fortifying herself with a liter of water and a couple of dissolved electrolyte tablets (Orange Creamsicle and Blue Raspberry, not a good mix) does Ysolt embark on the next stage of her plan, eventually threatening to turn off Dif’s voice function when he objects.

“You’re a Puritan,” she says firmly, pausing in the work of sawing off her chosen slab of salt. “You’re supposed to respect authority.”

“I am not of any specific faith! I have a Puritan name.”

“Yeah,” she says, wiping her gritty forehead. “And you know, I never got why Vivi thought Diffidence-towards-God Ellison was so funny. Now stop whining and get the bag.”

“There is a risk of — “

“I know, I know.” She carefully deposits the rectangular slab of salt, cut a little bigger than her measurements, into the bag Dif holds open and they climb back inside. It’s pitch dark now, not even the faintest thread of moonlight reaching this far into the abyss. Ysolt tries not to think about the depth of the ocean, or the various circles of hell. Which circle have they fallen into?

“Get the lights back on,” she says to Dif, and the drone moves around carefully, firing little bursts of infrared to orient himself, and activating the LED candles they took from her emergency kits, now magnetized to the walls as needed. Ysolt did not want to waste one precious percentage from the batteries on anything but the legs.

In the golden light, she re-measures, marks off the salt with her drafting pencil, hesitates, measures again. In her head, her mother says, Measure twice, cut once! and her father, an abstract painter, for whom this is a long-running joke, laughs. The thought of them gives her a strange and sudden pang, and a comfort, as if they would be right behind her if she looked.

She does not look. She measures one last time, not changing the pencil marks, then meticulously removes the last of the salt with her tiny hacksaw.

The taste on her lips was what did it, tasting not table salt but something else — something, she hopes, that will replace the broken piece of her chemical battery for just long enough to climb out. There are risks, as Dif cannot stop himself from pointing out; the fossil salt isn’t the same type as in the battery, it’s full of metallic inclusions, it’s not placed into the correct carbon-tube framework, it might generate explosive gas inside the casing … “But it might work,” she says now, replacing the cover and gingerly screwing the bolts back in, already worried about sparks, friction.

“There is a chance,” Dif says. “But without a more complete analysis of the salt — “

“Yeah, okay. A chance. Up we get. Oh, and put Module 32 back on its charger.”

“The bedroom is not complete,” a distant voice whines.

“Ignore it and put it back in its charger,” Ysolt says. “This is going to be a bumpy ride.”

“If it works,” Dif says.

“Well yeah.” She swallows hard and positions herself as best she can at the now-sideways control panel, spangled with cracks but functional, she hopes, a little longer. “Power on,” she says, and winces as something near the ceiling sparks, a pop of blue against the yellow of the emergency candles. “All power to transport, full speed.”

Back legs, front legs, back legs, front legs … the connected batteries with their new chunk of foreign matter start to whine, then scream, but the power indicator is at 88 percent, somehow. Fresh earth, a snowfall of broken salt, crushed tumbles begin to fill the house again; belatedly Ysolt realizes she should have covered up the hole in the wall they were using to get in and out. Somewhere a window smashes, maybe in her office. Can’t stop now, check on it later.

The catches on her front door rattle so loudly they are audible over the noise of the batteries, the crunch and roar of the legs. In a second — yes, there it goes, the door flies open and some of the new influx of earth drains out. Relieved of the weight, the house speeds up, throwing her against the wall, where she finds a grab-handle and clings for dear life.

The battery indicator flicks from 88 to 21, the color changing from green to red — surely an artifact of the sensor, as it goes back to 79, then suddenly to 20, then to 50. It occurs to her abruptly that it might not be the sensor’s doing but the kludged-together battery itself, and they are in more trouble than she thought.

“The angle is too steep!” Dif announces from somewhere.

“I’m on it!” Ysolt yells back. This is not entirely true, but if she manages the stilt function on the legs fast enough, the back ones can extend to a length that pushes the house closer to horizontal while the front ones scurry to move it upwards. Every bone in her body feels jolted loose. The noise from the batteries is becoming a howl, mingled with beeping from what seems like a dozen sources, only one of which she can identify as her smoke detector. “Is something on fire?” she shouts.

“The couch!”

“Collateral damage, forget it,” she yells, and with a gut-loosening lurch they are up and over, teetering, she can feel the swaying, and the battery indicator goes from 61 percent, orange, to 0, dark as the starless night above.

She registers these things at the same time: the sky, the blessed, beautiful, non-salt-hidden night sky, cloudy, a smudge of moon; the dead batteries, both of them; the faint glow of her burning furniture; and Dif, climbing frantically towards her, legs pistoning, reaching for her. He is trying to push her out of the hole in the wall, as the house, on its deadened legs, begins to slide back towards the abyss, and the force of his manipulators on her shoulders seems to snap her out of a trance.

Her terror is gone and her worry is gone and her guilt and shame and confusion is gone, all of the I don’t deserve saving. She is a creature of pure motion, grabbing Dif, Vivi’s friend, her friend too, clutching three legs in one hand, and tumbling free of the house, backwards onto the salt hardpan in a tangle of limbs and dust. The impact slams the breath out of her a split second before Dif’s round body catches her on the chin and does the rest of the job, and for several seconds she lies there dazed, waiting, she realizes, for the sound of her house — her life, her livelihood, her lessons learned — tumbling back down into the pit.

But there’s nothing; as Dif climbs off her, she gets to her feet and realizes that the entire pod, still tilted at an impossible angle, seems to be … caught on something.

“Cleaning cycle incomplete,” a voice murmurs, somewhat censoriously, underneath it.

“You have got to be kidding me,” Ysolt says. “Dif?”

“Coming.”

She and Dif struggle together to pull Module 32 free, its spiked treads clattering on the salt; the pod creaks ominously, the exterior squeaking as it shifts minutely, but it doesn’t fall any further. Small blessings. The main thing, hopefully, is that her GPS beacon signal can be perceived now, and the town will come and get her, will pull her house the rest of the way out. She thinks of birds flocking, scattering for a moment as predators approach, reforming smoothly into fresh shapes: safety in numbers. It is so rarely that one person rescues another. Even lifts another. The many always rescue the few.

“Look,” Dif says, and she looks, rubbing salt out of her eyes: Fourseven in the distance, the familiar pattern of panels and domes, the flying dots of the search drones with their blue and red lights. She’s never been so glad to see it in her life. She adjusts her glasses and looks down at the battered drones. “Okay,” she says. “Let’s just get our story straight, all right? We were never in any real danger, and the search and rescue teams were definitely supposed to prioritize rescuing other folks. Right?” She nudges Dif with her foot.

“We were in life-threatening danger,” Dif says.

“I was joking.” She sits down gingerly and rubs her chin. “I’m not good at it, you know that. Anyway, thank you for your help, both of you. And for reminding me to drink water. And everything.”

“No one has ever thanked me for performing my functions before,” Module 32 replies, startling her somewhat.

This is the longest conversation she’s ever had with Module 32, and the realization makes her smile, mildly chagrined. “An oversight on my part,” she says.

“You’re welcome,” it adds.

Dif sits next to her and tucks his legs in, and she absently puts her arm around him, just like she was always taught, because the more of you there are, the harder it is for the wind to take you away.

Premee Mohamed is a Nebula, World Fantasy, and Aurora award-winning Indo-Caribbean scientist and speculative fiction author based in Edmonton, Alberta. She has also been a finalist for the Hugo, Ignyte, Locus, British Fantasy, and Crawford awards. Currently, she is the Edmonton Public Library writer-in-residence and an Assistant Editor at the short fiction audio venue Escape Pod. She is the author of the “Beneath the Rising” series of novels as well as several novellas. Her short fiction has appeared in many venues and she can be found on her website at www.premeemohamed.com.

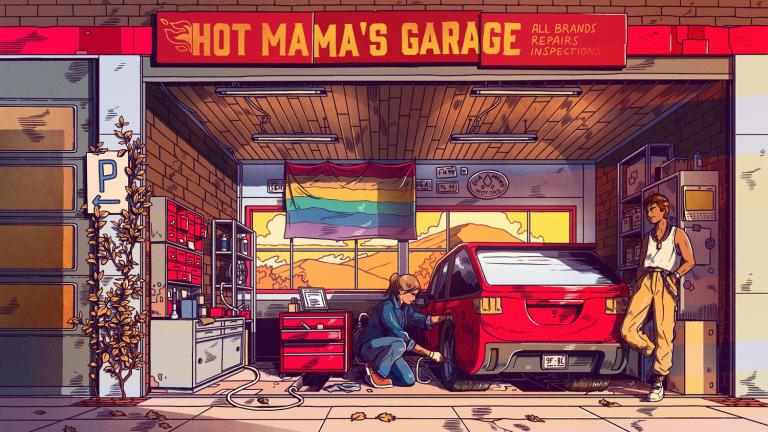

Lily Padula is an artist and illustrator who was raised in a small beach town about 100 miles from New York, and spent 15 years living in Brooklyn, NY, studying and later teaching at the School of Visual Arts. These days, she can be found in Connecticut, tending her garden and creating illustrations. A deep love for the natural world is a cornerstone of Padula’s work, which intermingles fantastic landscapes and abstract concepts. Her work can be found in magazines, books, newspapers. She also creates illustrations and short animated documentaries for non-profits.